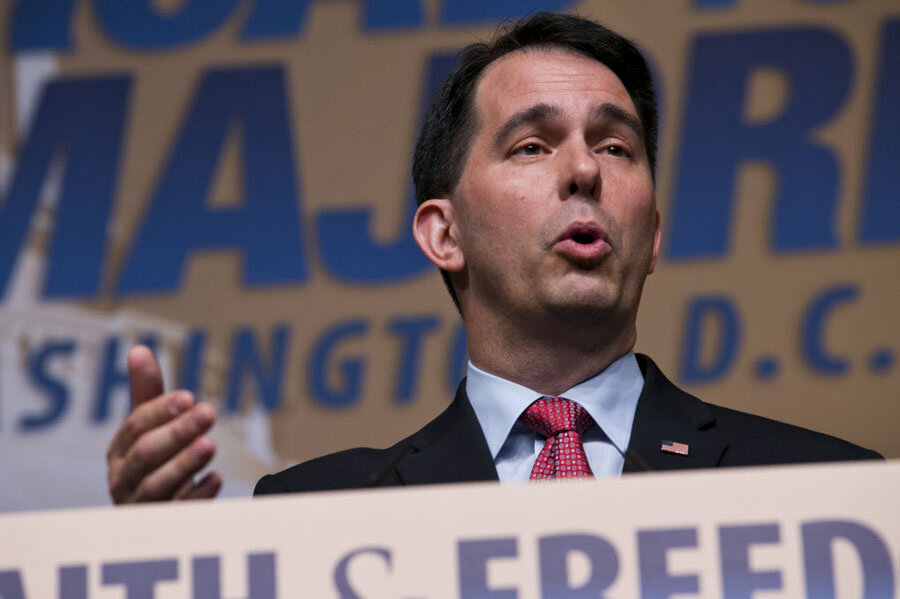

Scott Walker 2016: rock star or villain?

Loading...

| Washington

Gov. Scott Walker of Wisconsin is unique among the Republican hordes running for president: He is deeply polarizing within his own state, and almost certainly the most polarizing governor in the country.

Most Wisconsin Republicans love him, even if his numbers have declined a bit lately, while most Democrats can’t stand him. And therein lies both the promise and the peril of Governor Walker’s presidential candidacy, which launches on Monday.

Walker is a rock star to many national Republicans for pushing an aggressively conservative agenda and for winning statewide election three times in four years in a battleground state with a rich progressive history. In 2012, he became the only governor in US history to survive a recall election, spurred by his successful drive to limit the collective bargaining rights of most state public workers. In short, as far as conservative voters are concerned, Walker has a proven track record both on policy and in electoral politics.

“That’s a really helpful narrative for him on the campaign trail, while he’s trying to win in these early primary and caucus states,” says Barry Burden, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. “The fact that he’s the enemy of the Democrats and of unions is a positive in the nomination race. It’s made him sort of a hero.”

But if Walker wins the Republican nomination, his divisive record is likely to cut differently – especially if he hopes to attract moderates. He won’t be able to say, “I was a uniter, not a divider,” or that he appealed to minority populations, the way then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush did in 2000 on his way to the presidency.

Walker also won’t be able to say that he worked effectively across the aisle – a negative to voters who want Washington to move beyond its hyper-partisan ways. After last November's elections, Americans reported a much stronger appetite for political deal-making than after the 2010 midterms, according to a Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll.

Walker’s style “is one way to govern, but it’s not a centrist or encompassing way to govern, and he’ll have to explain himself to the average general election voter in the fall [of 2016], if he gets that far,” says Professor Burden.

Walker wasn't the only force behind the polarization of Wisconsin politics, but he contributed to it, analysts say. "The broad middle that existed back when Tommy Thompson was governor back in the 1980s and '90s, a lot of that has evaporated," Burden says. "People have chosen sides around Walker pretty quickly, really from his first days in office."

In the state legislative session that just ended, the Republicans – who control both chambers – gave Walker “a going-away bag full of goodies to sell on the campaign trail,” as Bloomberg News put it. He won a ban on nearly all abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy, expansion of school vouchers, drug testing for people on public assistance, an end to the state's "living wage" law, big funding cuts to the University of Wisconsin, and an end to job security for tenured faculty. Earlier this year, he signed two bills expanding gun rights, and in another blow to unions, legislation making Wisconsin a so-called “right to work state.”

The question, though, is how Walker will be perceived on the national stage. Most voters don’t pay attention to Wisconsin politics, and the fact that he’s a divisive figure at home doesn’t automatically translate nationally.

The polarization of Wisconsin politics “was formed in the crucible of Act 10 and the demonstrations over that,” says Charles Franklin, pollster at Marquette University Law School in Milwaukee, referring to the measure that pared back collective bargaining rights. “The country is not going to learn about Scott Walker in that same context.”

The issues of the 2016 election will center on the national economy, security, immigration, and health care. Over time, as he has prepared to run for president, Walker has marched to the right. In March, he acknowledged on Fox News that he had changed his mind on immigration, and now opposed a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants as part of comprehensive reform; in 2013, he had favored a long-term path to citizenship. And he reversed course on “right to work”; in 2012, he said he had "no interest in a right-to-work law in this state."

Voters also will base their assessments of Walker on perceptions of character and leadership. On the latter point, Walker has his argument down. He burst into the top tier of likely Republican presidential candidates in January, in a fiery speech touting his governing record at the Iowa Freedom Summit in Des Moines.

“We weren’t afraid to go big or go bold,” Walker told the crowd, to thunderous applause.

That message “sells really well with Republican activists,” says Burden. “They like to see that he’s done something, in contrast to, say, the senators who are running against him. He’s been implicitly picking on them, saying, ‘These are people from Washington who talk a lot, and I’ve actually gone out and done things. Balanced budgets, changed gun laws, changed tax rates…' "

Walker’s biggest liability, perhaps, is the ongoing “John Doe” criminal investigation into whether a conservative group improperly coordinated with Walker’s 2012 recall campaign. Critics also talk about sluggish job growth in Wisconsin; the state is 35th out of 50. But Walker counters with a state unemployment rate (4.6 percent in May) that’s below the national average (5.5 percent in May).

Walker has been working on getting up to speed for his debut as a national candidate. Earlier in the year, he struggled in public to answer questions about his views – on evolution, on Ukraine, on the Islamic State – earning embarrassing headlines. As other candidates were announcing their campaigns and undertaking heavy public schedules, Walker was finishing his legislative session and studying up on domestic and foreign policy.

At home, his overall approval rating has dipped in recent months, going from 49 percent last October to 41 percent in April, according to the latest Marquette poll. Among Republicans, he dropped 8 percentage points, into the high 80s, which is still quite high. Approval among Democrats is below 10 percent.

Still, Walker starts his campaign with a deep reserve of goodwill among the key segments of the GOP, both in Wisconsin and nationally: the “establishment,” social conservatives (he’s the son of a Baptist preacher), tea party conservatives, and libertarians. Walker leads polls of Republicans in neighboring Iowa, averaging almost 18 percent in a field of 16 candidates, according to the RealClearPolitics polling average.

Now the heat is on. Expectations are high, and if he loses the Iowa caucuses in February, the first nominating contest, he’ll look defeated.

Walker “has to win Iowa,” says Republican strategist Ford O’Connell. “It all comes down to Iowa.”

Walker’s top competitors for the nomination are the two Floridians, former Gov. Jeb Bush and Sen. Marco Rubio. “His biggest problems are Bush’s money and Rubio’s compelling narrative,” says Mr. O’Connell.

On Thursday, Team Bush announced an unprecedented fundraising haul of $114 million for the second quarter of 2015, between his campaign and his super-political action committee.The challenge from Senator Rubio comes thanks to his back story as the son of Cuban immigrants, and his appeal to Latino voters in the general election.

Walker’s narrative of “bold action” also brings with it a geographic appeal – its center in the American heartland, and the argument of relatability.

Walker can say, “I’m an average Joe, I’m not Mitt Romney, I’m not ultra-rich, I can identify with people,” says Professor Franklin.

The fact that Walker never finished college is another element of his biography that could make him relatable to some voters, but could hurt with others.

Another Midwest Republican governor, John Kasich of Ohio, gets in July 21, bringing the field up to 16 official candidates. The first debate is Aug. 6. The race for 2016 is still just starting.