CNN out, Breitbart in: Our reporter on what the new Pentagon ‘rotation’ means

Loading...

| Washington

The Pentagon press room hasn’t changed much since I started covering the U.S. military at the height of America’s war in Iraq.

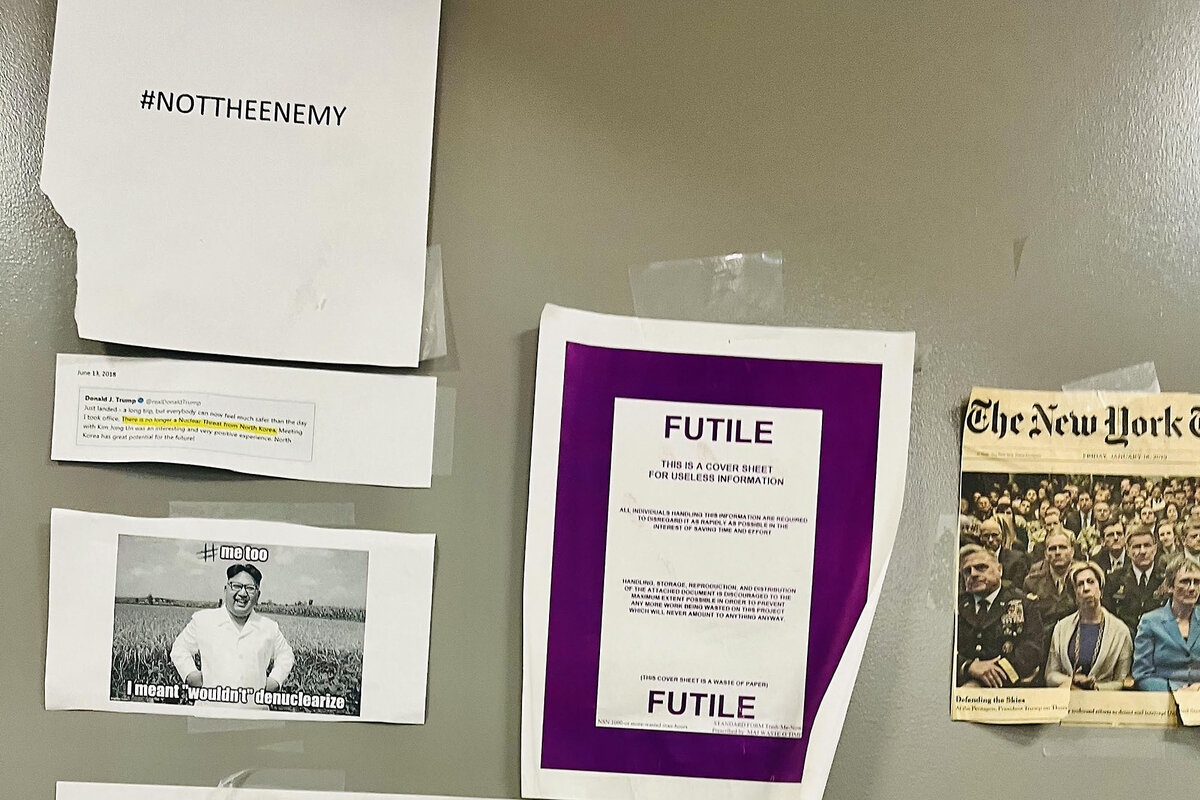

When I saw it for the first time, I thought it looked a lot like my college newspaper offices: a sizable array of snack wrappers, cubicles, and a satellite map of the Korean Peninsula at night, the bright lights of the democratic South set against a Northern dictatorship perpetually plunged into darkness.

The big difference, of course, was the experienced reporters. In the Pentagon press corps there are always a few newbies as I was, but we were thankfully surrounded by some of the best journalists in the business – charming and chatty, but tough, and immersed in the ins and outs of the American military.

Why We Wrote This

The United States has maintained the most open defense department in the world for journalists, our military reporter writes. Recent changes to the Pentagon press corps are shaking up the relationship between the fourth estate and defense forces.

I still cover defense, but now I report on global security, too, from Brussels. The timing of my latest trip back to Washington came just days after Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s office announced that Pentagon press corps members NBC, The New York Times, and NPR must “rotate out” of their longtime office spaces to make room for Breitbart News and One America News Network, outlets that have been vocal in their support of President Donald Trump. (HuffPost, which leans left, was also provided with new office space.)

When the Pentagon Press Association protested Secretary Hegseth’s move, the administration doubled down on the number of outlets “rotating out” of their spaces to include CNN, Politico, and The Washington Post. The deadline for their departure is Friday.

In my reporting on defense departments and militaries around the world – from the Pentagon to Iraq, Afghanistan, and NATO headquarters – I’ve seen battlefields and turf wars. But what’s happening now at the Pentagon is a first.

How reporting at the Pentagon works

Being an amateur when I arrived in 2006, I figured the Pentagon was going to be an oppositional place – we wanted facts, and defense officials didn’t want to give them up. There’s plenty of that, but I also met many folks delighted to shoot the breeze with reporters – to spin, sure, but also to share the news and to learn.

More than one spokesperson told me, early in their tenure, that they learned more from veteran journalists covering the beat than they imparted in terms of policy when they started the job.

The press corps does its reporting in large part by roaming the halls of the Pentagon. It’s the most open defense department in the world – rare in that while there are classified corridors, credentialed reporters can go almost anywhere else in the building, dropping by offices to chat or heading down to the food court for Starbucks.

The public work of the press takes place in the briefing room. Question-and-answer sessions with defense officials are broadcast on the Pentagon’s online channel and by the networks when there’s breaking news. By tradition, The Associated Press asks the first question, and then the rest of us take a turn, pursuing our own queries or following up on colleagues’ questions when it seems they’re being evaded or the answers from the podium are unclear.

In this way, the press corps works as a team of sorts. It travels together, too, with defense secretaries and military officials on around-the-world trips. It’s a tight group.

And so it was as a group that the Pentagon reporters reacted with alarm to the announcement earlier this month of a new annual “media rotation program.”

In a memo outlining the specifics, the acting assistant to Secretary Hegseth, John Ullyot, strikes a tone, critics say, at the intersection of gracious patronage and veiled threat. He builds the case that Pentagon space – on loan from the defense secretary, he emphasizes – is a privilege the press enjoys at the pleasure of Mr. Hegseth. The words “loan” and “enjoy” are used several times in the succinct memo.

The outlets vacating offices they have occupied, in some cases for decades, will still be able to cover briefings and be considered for travel, Mr. Ullyot writes. This, he says, “stands as a tribute to the importance the Department has long placed on informing the public about the U.S. military and all it does to project peace through strength. It also honors the many correspondents who put their lives on the line, and in many cases died, while covering our finest in battle.”

Statements of protest released by news organizations in the wake of the memo point out that their presence in the building is thanks to the U.S. Constitution, with a Bill of Rights that guarantees freedom of speech, rather than because of the largesse of any particular defense official or president.

Pattern of punishing the press

There’s growing concern, however, that the Defense Department memo fits a growing pattern of administration efforts to constrain the press and to make it more submissive. The White House announced last week, for example, that The Associated Press would be barred from attending Oval Office events or flying with the president on Air Force One until it uses the new name President Trump has chosen for the Gulf of Mexico – the Gulf of America. (The news agency, which produces stories that many other media outlets publish, has said it will continue to use the term Gulf of Mexico, while also acknowledging the name change.)

Punishing a news group that “refuses to conform to government-imposed language is more than an attack on one reporter or outlet – it is an assault on the First Amendment,” the National Press Club wrote in a statement last week. “The role of the press is not to take orders from the government but rather to hold the government accountable.”

The U.S. troops, commanders, and defense officials whom journalists cover, while often great people and leaders, are not always “our finest,” as Mr. Ullyot puts it, due to bad decisions, cavalier accidents, ineptness, or self-serving cover-ups, to name a few such scenarios.

They do, however, have at their disposal billions of taxpayer dollars – the Pentagon spends more on defense than any other country, accounting for 40% of the world’s total military spending – and a state-sanctioned license to kill. It’s through the press that Americans can track and question the money and power at work here – and the troops’ lives that are on the line in support of U.S. policies.

Career defense officials say the new administration never asked whether there’s enough space in the press room to accommodate more journalists before drafting the memo. There is, they add, room for all the outlets they cite without ejecting any.

This fuels concern that the new policy amounts to a personal attack on the reporters who broke news about Mr. Hegseth’s troubled marriages, a rape allegation, and his struggles with alcohol in advance of his confirmation hearings.

Troops protect freedom of speech

Many in the military find the latest developments as disturbing as journalists do. As when I covered the U.S. war in Iraq, some troops are excited to meet a reporter; others are guarded and want nothing to do with us. But they take an oath to fight to defend the Constitution, which includes freedom of the press.

In the not-a-fan camp was an Army infantry commander who tolerated my presence but didn’t want me traveling with him during operations.

As a result, when his Humvee was hit by a roadside bomb, I was not with this commander but rather in the vehicle right behind. The driver gravely wounded, his fellow soldiers loaded him into our vehicle. As the convoy prepared to rush back to base for medical care, they cradled his head, comforting him while he convulsed and threw up.

After the soldier was delivered to U.S. military medics awaiting his arrival, our driver, a young private, started crying, convinced in the stress of the attack that he hadn’t driven quickly enough. His teammates hugged him and then held his cheeks in their hands, forcing him to look in their eyes so they could tell him that they, never in their lives, had seen a Humvee go so fast as he’d driven to get his friend back to base after that bombing.

When the commander called his troops together later that evening, he told me to leave before he shared an update. The troops beside me, gently, protested. I’d been in the bombing, too, they noted, nodding in the direction of the soldier’s vomit on my clothes. I stayed. We learned together that the soldier had died.

Today, there’s an addition to the Pentagon press room, a sign on the door that reads, simply, #NotTheEnemy.

It was taped there by a reporter, most likely – I haven’t asked around – but perhaps by a supporter who believes that though we stand apart, we’re as much a part of the place, and of its defense of freedoms, as anybody else in these halls.

Editor's note: This story, originally published on Feb. 21, was updated to note the inclusion of HuffPost in the press rotation program.