Court pushed abortion back to the states. It isn’t staying there.

Loading...

| CARBONDALE, ILL.

This time last year, Carbondale had zero abortion clinics. Now, this college town of fewer than 22,000 people has two – and lots of out-of-state visitors.

The majority of license plates in Choices Center for Reproductive Health’s parking lot are not from Illinois, but from neighboring states: Missouri, Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.

A few miles away at Alamo Women’s Clinic, the other clinic to open here over the past several months, an employee estimates that “.0002 percent” of their patients are from Illinois. Every day “is crazy,” says another employee. She estimates that the clinic performs about 50 abortions per day: 25 surgically, 25 with a pill.

Why We Wrote This

Returning abortion policy to the states is proving complicated, as some states’ choices tangibly impact their neighbors, and courts clash over abortion pills sent through the mail.

Fridays and Saturdays are even busier. Those days are more convenient for out-of-state travel.

As nearby states have passed more and more restrictions on abortion over the past several years, the southern tip of Illinois, and Carbondale specifically, has become a hub for abortion access. And since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last June, interstate health care commutes across America have skyrocketed.

In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the court ruled that the Constitution does not grant a right to abortion, writing that the authority for regulating abortion would be returned “to the people and their elected representatives” in individual states.

But this simple pronouncement – in a country where people can cross state lines to get an abortion, or receive abortion pills through the mail – has led to a complicated, confusing reality, legal experts say.

A dozen states have banned abortion, with some exceptions, while even more have expanded protections, according to an analysis by the Guttmacher Institute. In many places, pregnant women and physicians alike say they are unclear about what’s allowed and when exceptions apply. Moreover, the rules keep changing as new lawsuits are litigated and state legislatures debate additional measures – including trying to enforce abortion restrictions across state lines, a prospect that has paralyzed some providers even in states where abortion is legal.

Last week, the accessibility of a popular abortion pill was thrown into doubt by two conflicting federal court decisions in the space of a few hours – a dispute that will likely go to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“The legal landscape is even more chaotic than it was before,” says Kimberly Mutcherson, co-dean and a professor at Rutgers Law School.

“The Supreme Court’s desire to get out of the abortion business – it’s just not going to happen,” she says. The web of cases and conflicting rules emerging in the wake of Dobbs “aren’t just raising questions about abortion, but are raising fundamental questions about federalism, about the power of the federal government, and about the relationships between states.”

Conflicting abortion pill rulings

The legal landscape is poised to become even more complicated, as state and federal courts wrestle with questions untested in over a century. Amid shifting state laws, federal litigation has continued, including the recent flurry of federal district court opinions concerning the use of mifepristone, a popular abortion pill.

Approved in 2000, and approved in other western countries earlier than that, mifepristone is one of the most tightly regulated prescription drugs in the country. But a federal district judge in Amarillo, Texas, last Friday temporarily paused the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) decades-old approval of the drug. While the ruling didn’t go as far as the plaintiffs bringing the case hoped it would – and the judge gave the Biden administration seven days to appeal before the decision goes into effect – it is a rare instance of a federal court temporarily suspending FDA approval of a drug over the objections of the agency and the manufacturer.

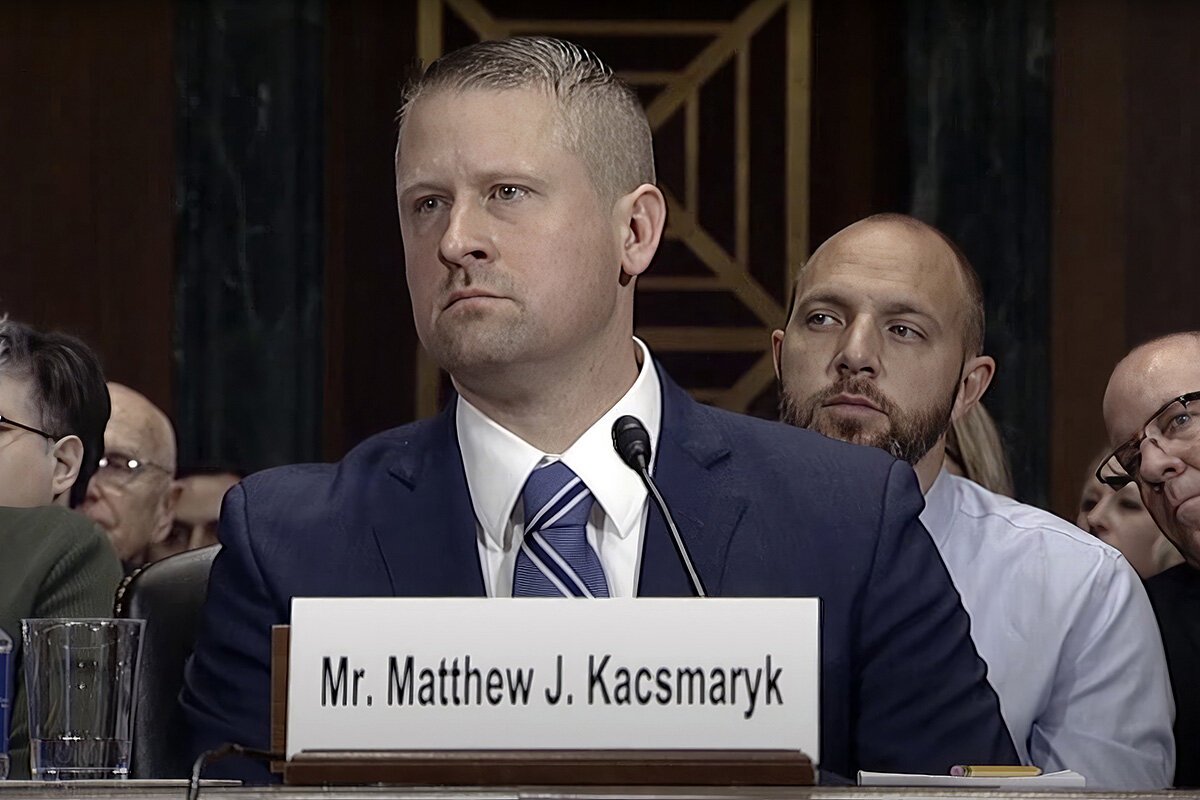

“Simply put, FDA stonewalled judicial review – until now,” wrote U.S. District Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk in his ruling.

Just hours later, over 1,500 miles away, U.S. District Judge Thomas O. Rice, in Washington, temporarily blocked the FDA from “altering the status quo and rights as it relates to the availability of mifepristone.”

The litigation has returned the abortion question to federal courts less than a year after Dobbs. There are additional legal questions as well, ranging from an obscure 19th century anti-vice law to federalism and separation-of-powers concerns. Last week’s conflicting district court orders all but ensure the Supreme Court will be asked to weigh in.

In his ruling, Judge Kacsmaryk wrote that sending abortion pills through the mail violates the Comstock Act, an 1873 law that made illegal the mailing of “obscene” material, including anything “intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of an abortion.”

His interpretation echoed that put forward by Republican attorneys general in the Texas case, who also argued that the drug’s availability undermined their ability to regulate abortion. The ruling also directly contradicts a nonbinding opinion last December from the U.S. Department of Justice, which said that abortion medication can be mailed if the sender “lacks the intent” that the drugs will be used “unlawfully.”

While the availability of mifepristone has not changed overnight, legal experts say, the Texas ruling in particular broke new legal ground in the realm of both reproductive and states’ rights.

The Texas court “is using arguments around an agency’s power to interpret its own statute and apply it, counter to all evidence,” says Rachel Rebouché, dean of the Temple University Beasley School of Law. The ruling, she adds, “deprives states of being able to regulate abortion the way they want.”

Pulling mifepristone off the shelves nationwide, Democratic state attorneys general have argued, would endanger abortion access in states where the procedure is legal.

That includes states like Illinois, says Danika Severino Wynn, VP of abortion access at Planned Parenthood. Mifepristone has been used by more than 5 million people, she notes, and over half of all abortions performed in the country are done with medication, not surgery. Providers would still try to give patients options for care with a similar drug, misoprostol; however experts say this drug is not as effective when used on its own.

“We know [mifepristone] is safe,” says Ms. Severino Wynn, who is also a midwife by training.

And in states like Illinois, where clinics located near the borders of abortion-restrictive states already have high wait times, “those wait times will go up even more” if access to mifepristone is restricted, she adds. “This will have ripple effects.”

A town divided

Six months after the Alamo Women’s Clinic opened its doors in Carbondale, there’s still no sign on the building.

Employees tried to buy a sign shortly after moving their clinic almost 1,000 miles north from San Antonio, Texas, where the name “Alamo” is far more apt. But when the sign-maker learned that the clinic provided abortions, the company refused Alamo’s business. Now, the clinic plans to stay signless for the time being. Patients tell them they like the anonymity, and it’s helped discourage protesters, who often encircle abortion providers.

Not surprisingly, Carbondale’s emerging identity as an abortion haven has split the town.

“I think it’s a good thing,” says Amber Segler, working behind the counter at a local vegetarian restaurant. “I like that we’re becoming a safe space for women. I like that about my community.”

Other residents, however, have watched the changes with mounting dismay.

“For the majority of people in this area, it really is appalling that it’s taking place here,” says Pastor Mark Surburg, from inside his office at the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church in nearby Marion, where illustrations of fetus development hang in the hallway. Mr. Surburg has been a leader of the area’s opposition efforts through the Southern Illinois Pro-Life Alliance, a group of about 50 churches in the area who joined together to coordinate “sidewalk counseling” outside the new clinics.

“Illinois, through its legislation, has sort of sought to make itself the death capital of the Midwest,” says Mr. Surburg, who keeps a stack of fact sheets on the Illinois Reproductive Health Act in his office to distribute to reporters.

This act, which was signed into law by Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker in June 2019, grants residents the “fundamental right” to abortion care. In January Governor Pritzker signed a follow-up piece of legislation, HB4664, which protects women traveling to Illinois for abortions from other states.

“The Dobbs decision brought a lot of momentum, sadly, for the other side,” says Brian Westbrook, executive director of the St. Louis-based nonprofit Coalition Life. The Supreme Court ruling “changes the landscape,” he adds. “Now we fight the battles state by state.”

In a concurring opinion in Dobbs, Justice Brett Kavanaugh forecast some of the legal turmoil now playing out at the state level. Specifically, he wrote that the constitutional right to interstate travel would allow a woman to travel to another state to obtain a legal abortion.

That question is very much on the minds of abortion-protective and abortion-restrictive states. Since Dobbs, 10 states have enacted “shield laws” that protect, to varying degrees, in-state providers and out-of-state patients from prosecution by other states. In April, Idaho became the first state to implement a so-called “abortion trafficking” bill.

The law doesn’t explicitly criminalize leaving the state to obtain an abortion, but it does prescribe a two- to five-year prison sentence for any adult who tries to help a minor obtain an abortion without their parents’ consent. This would penalize adult friends or relatives who help a minor travel out of state, or even if they travel out of state to buy abortion medication to bring back.

“What we want to make sure of is that parents are the ones who are in charge of their children. Parents are the ones who need to be involved in helping to make these decisions,” Barbara Ehardt, a Republican state representative who sponsored the law, told HuffPost in March.

Reproductive rights groups have promised a legal battle over the Idaho law. This kind of law is untested, and possibly unprecedented, legal experts say. One possible analogy is the fugitive slave laws of 1793 and 1850, which required all states, including abolitionist ones, to return runaway slaves to their owners. That was a federal law, however, and it has typically been federal law enforcement that has prosecuted criminal acts across state lines.

“Right now the understanding between states is we want to respect the rules in your jurisdiction,” says Professor Mutcherson at Rutgers. “But once we start going down a path where [states] want to pick and choose what rules we’re going to respect, and there’s no federal constitutional hook to keep people in basically the same realm, then you do start to worry.”

Waiting for legal clarity has had its own impact, however. With so much uncertainty around the future of mifepristone – and in the abortion landscape more generally, such as the untested questions around interstate enforcement – chilling effects have become widespread.

Walgreens announced in early March that it wouldn’t distribute abortion pills in 21 states where GOP attorneys general were threatening legal action, Politico reported. (In January, the FDA expanded the availability of abortion pills to include retail pharmacies for the first time; Walgreens says it is currently seeking certification to distribute the pills in certain states.) And physicians, many of whom are licensed in multiple states, have been concerned about possibly having their licenses revoked for providing abortion care in a state where it’s legal for a patient from a state where it isn’t.

“Typically if a physician’s license is revoked or suspended in one state, other states where the physician is also licensed will be notified. This could be a catalyst for the physician’s license to be revoked or suspended in these other states” even though the physician has acted within the law, says Joanne Rosen, a senior lecturer at Johns Hopkins University. “It’s really introduced a chilling effect on physicians who are licensed in other states and fear that being initiated against them.”

Perhaps the most dangerous legal confusion has been reported in states with strict abortion bans, however, where exceptions to the ban – often to preserve the life of the mother – have been unclear to the physician, the patient, or both. In Texas, for example, five women who say they were denied medically necessary abortions have filed a lawsuit asking the state to clarify when the procedure is medically permissible.

“Without that clarity what we have been seeing, and rightly so, is people have been being extremely cautious,” says Professor Mutcherson.

State legislators “haven’t stepped in to clarify what their medical exceptions mean,” she adds. “What I don’t want is for someone to have to die before we figure these things out.”

Henry Gass reported from Austin, Texas; Story Hinckley from Carbondale, Illinois.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story stated that Walgreens announced that it would not distribute abortion medication in any state; in fact, although the pharmacy is not currently dispensing the pills, it is seeking certification to do so in certain states.