Why free lawyers shouldn’t come cheap

Loading...

| Leesburg, Va.

Ryan Ruzic has just about reached the point in his public defender career where he’s supposed to stop being a public defender.

With nearly five years’ experience he’s one of the veteran lawyers in his office, but he’s now supposed to be at a breaking point. The well of energy and youthful idealism that fueled working long hours for low pay against better-resourced opposition typically runs dry at this point, and the realities of supporting a family and paying off student debt usually drive young public defenders to the greener pastures of private practice right when they’re mastering their jobs.

He hasn’t reached that point yet, and he hopes he never will.

“I could absolutely see myself doing public defense for the rest of my career,” he says. “It’s an upward climb ... but I want a job that feels like it matters, and I want a job that I enjoy doing, and this job gives me both those things.”

Mr. Ruzic is a portrait of much that is right with the American legal system. But he is also a symbol of how it has become, in the eyes of many officials and experts, badly out of balance, potentially breeding mistakes and putting public safety at risk.

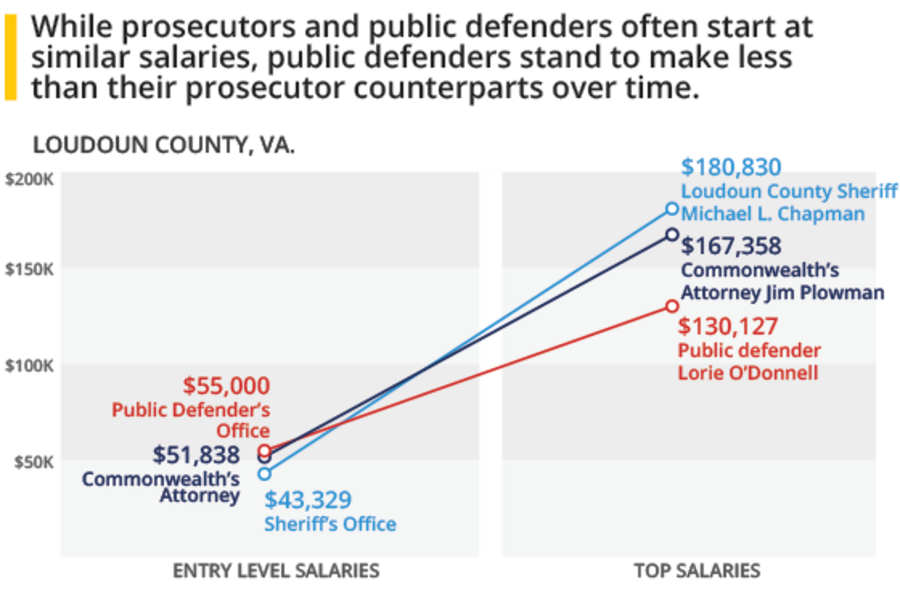

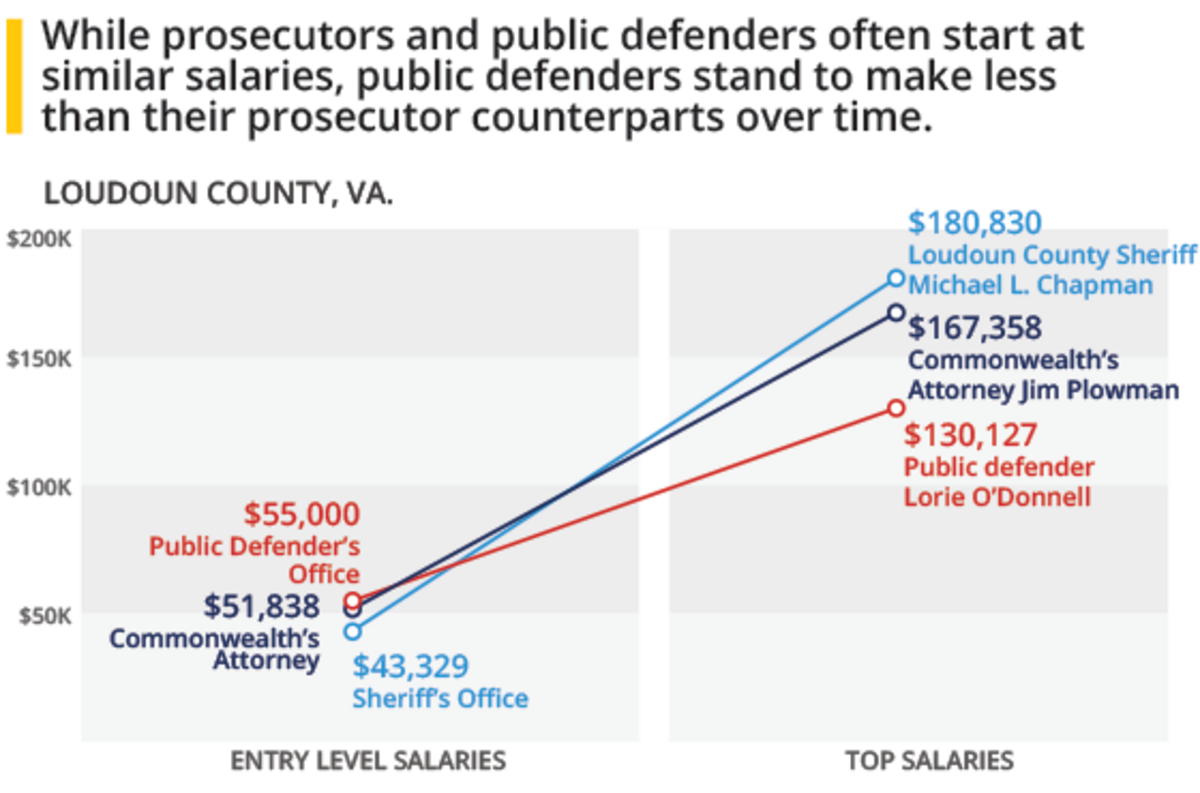

In Loudoun County, Va., where Ruzic works as an assistant public defender, the police department gets $84 million, county prosecutors get $3.3 million, and public defenders get $2.1 million. Put another way, 98 percent of the criminal justice spending in the county is arrayed against Ruzic.

And this is in one of the better-resourced jurisdictions in the country.

No one is saying police and prosecutors get too much money, here or elsewhere. They’re scrambling to do the best they can with limited resources, too.

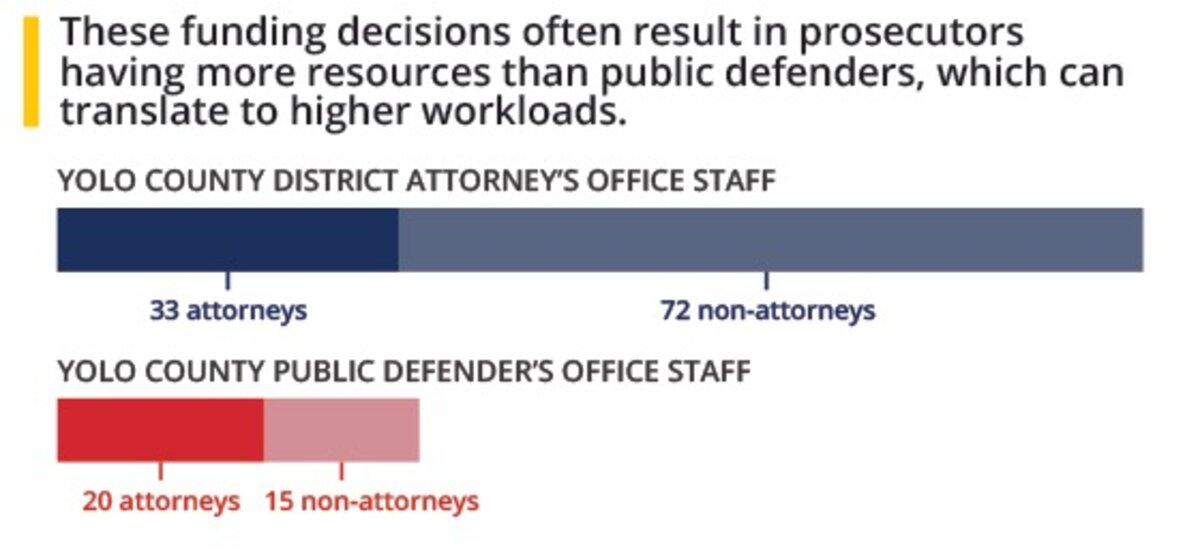

But there’s also little dispute that police and prosecutors – with their comparative financial advantage – are producing a workload that public defender offices are straining to cope with.

At any given moment, Ruzic has between 100 and 125 open cases. Each month usually brings 20 to 30 new clients, one or two jury trials, and one bout of major burnout. Some public defenders have twice that caseload. Some prosecutors make twice his salary.

The stress is inherent in the American view of justice. Those trying to put people in jail get the money, says Stephen Saltzburg, a professor at The George Washington University Law School in Washington.

“Most people would rather pay for prosecutors and police to do their jobs than they would to spend money on defense, even though the reality is if they were ever arrested and charged with a crime, they would conclude that no amount of money was too much to ensure them a fair trial,” he says.

Moreover, the United States has more laws and makes more arrests than most other countries, he adds, but the funding isn’t there to handle the workload.

Indeed, many of those nations often have a heavier emphasis on rehabilitation.

“Most countries give people treatment. We aren’t willing to do that until they commit a crime,” he adds. “We’ve been relying on the criminal justice system and punishment to deal with social problems.”

The public defense systems that represent more than 80 percent of those charged with felonies are overworked and underfunded to the point of a national crisis, said former Attorney General Eric Holder in 2013.

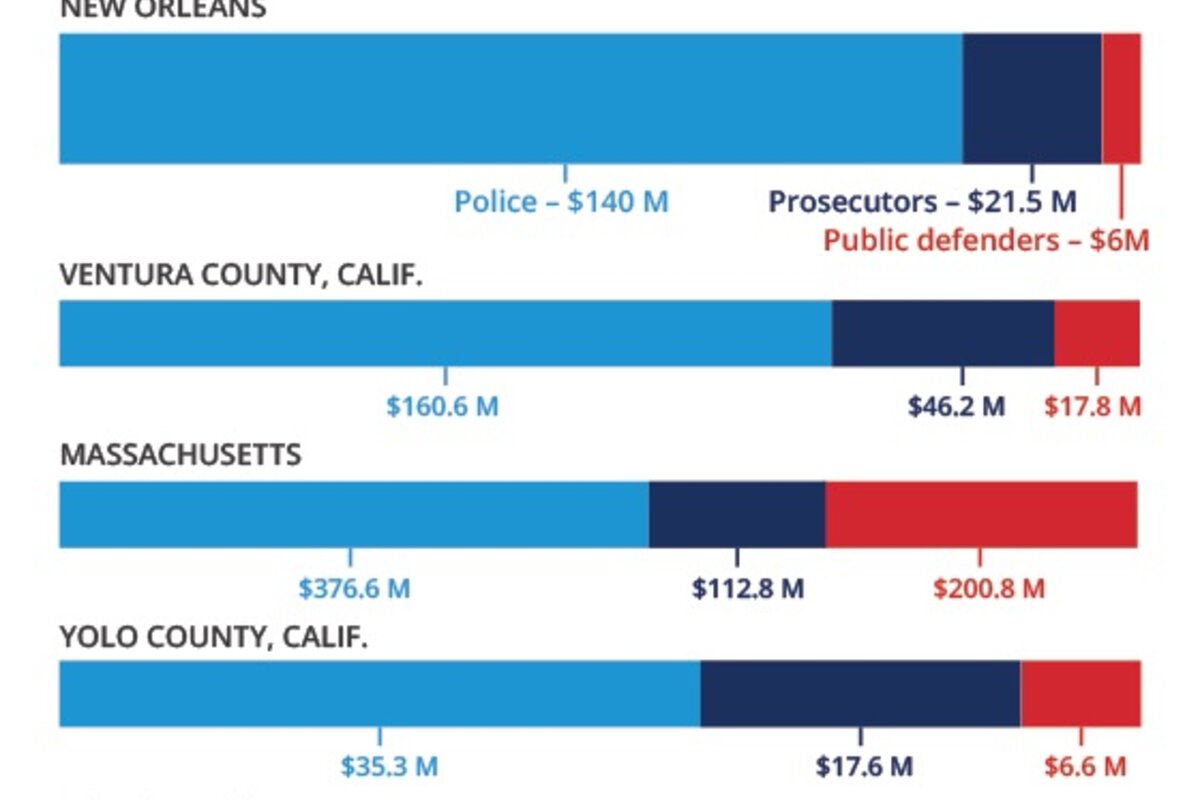

Take New Orleans. In January, Chief Defender Derwyn Bunton ordered a work stoppage on certain felony cases, citing staffing shortages, budget cuts, and staggering caseloads.

Orleans Public Defenders has a $6 million budget and about 82 full-time employees. The Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office has a $14.5 million budget and 210 employees. The New Orleans Police Department receives $140 million.

Mr. Bunton says these disparities are not unrelated to the fact that New Orleans has the highest incarceration rate in the country, and that Louisiana has one of the highest rates of proven wrongful conviction in the country.

“You have a DA’s office whose budget on paper is twice yours ... and then they’re partnering with a $140 million police force and federal partners to generate work,” he says. “We can’t handle the work generated by other actors in the system.”

Needed: 122.8 defenders

Some states have attempted to address the disparity issues, though they have seen mixed results.

Since 1992, Tennessee has mandated that any increase in local funding for a district attorney general must be accompanied by an increase of 75 percent of that amount for the public defender office. Yet a 2007 study found that “indigent prosecution funding was two-and-a-half times greater than indigent defense funding,” and that both offices were understaffed.

To meet proper caseload standards, the report found, district attorneys needed an additional 22 lawyers, while public defenders needed an additional 122.8.

In Yolo County, Calif., the public defender office has its own agreement with the county administrator’s office: For every three criminal prosecutor positions the district attorney adds, the county will fund two new public defender positions.

“I feel very lucky,” says Tracie Olson, the Yolo County public defender. “The parity ratio is a recognition of the fact that resources need to be as equalized as possible.”

Yolo County illustrates the importance of a commitment to parity. At the other end of California, in Ventura County, the county’s public defender is resigned to the fact that his office will never achieve resource parity.

Steve Lipson doesn’t think his office is underfunded, but the local district attorney’s office has more than double the funding and staff.

“If you’ve been in this business for any amount of time, it’s a given to accept that the playing field is not balanced,” says Mr. Lipson. “You have two options: You can rail against it and complain, or you can suck it up and do your best.”

$210,000 of student debt

In Loudoun County, rather than try to increase the number of people on staff, the chief public defender, Lorie O’Donnell, is eyeing pay parity with the commonwealth’s attorneys – a more achievable, but equally seismic goal.

“When it comes to buying a house or starting a family we lose them, just because the salary’s not there,” she says, referring to experienced lawyers. “Right now, just when they’re getting great, they go out into private practice.”

This is why Barry Zweig felt he had to quit as a public defender in Loudoun County in 2001.

It was an accumulation of factors, he describes: He was making the same kinds of arguments so often that judges got tired of them, and he was tired of constantly losing cases, “getting beat up by the system,” and working 45 minutes away from his son in day care.

“And at that point, after 4-1/2 years, I felt like I was underpaid,” he adds. “When you have a built-in reason like, ‘I have a child who’s 45 minutes away,’ it’s easy to make that decision.”

Ruzic is now in Mr. Zweig’s position – four years in and sitting on $210,000 of student debt. But he shakes it off.

“It’s a decision you have to make, and I decided I’d rather do something that I really like doing for the rest of my life than not be in debt for the rest of my life,” he says.

For others it’s not so easy. Public defenders in Massachusetts were the lowest paid in the country, according to a 2014 study by the Massachusetts Bar Association (MBA). Many worked part-time jobs to make ends meet.

District attorneys in the Bay State weren’t much better off, with entry-level prosecutors getting paid less than courthouse custodians.

As in Virginia, public prosecutor and defender offices were serving as de facto training schools for lawyers headed to the private bar for higher pay and a softer caseload.

“They’re losing a lot of talent out the door, and wasting a lot of energy and resources training people,” says Martin W. Healy, chief legal counsel of the MBA.

A budget approved by the state House of Representatives earmarks $500,000 to raise salaries in the state’s 11 district attorney’s offices, something Mr. Healy describes as “a step in the right direction.” But he has many of the same concerns as Bunton.

“If those people aren’t staying to garner that experience, the whole system suffers,” he says. “Either someone is convicted or serving a sentence longer than they would have been if they had more seasoned counsel, or someone’s walked out of the courtroom doors that deserves to be penalized.”

Prosecutor offices have their own challenges, even if they enjoy a resource and salary advantage over their defense opponents.

Prosecutors’ low pay makes the private bar just as alluring. And since prosecutors are tasked with investigating all possible cases – while defense lawyers are required only when charges are filed – they usually have higher caseloads.

Now, there is also growing pressure to make sure charges are appropriate. Last year saw a record 149 exonerations in the US, thanks in large part to more prosecutor offices actively looking for wrongful convictions.

A cause for hope

If there is one positive that experts and lawyers across the country can agree on, it’s that there is now an almost unprecedented level of public and political attention on the criminal justice system.

Politicians at the state and federal levels are passing reforms on everything from how defendants are sentenced to how they’re treated when they’re in prison and how they’re able to reintegrate into society after they are released. Criminal justice reform has united an often-polarized Congress, while conservative mega-donor Charles Koch and his liberal rival, George Soros, have been teaming up to push further.

“I certainly think there’s more focus from the public on some of the problems we see in the justice system,” says Ruzic. “I hope this is the beginning of a trend, and not just one of the many ups and downs an issue is going to see as it moves along.”

Much of the increased attention has been driven by negative press around the record exonerations and mounting lawsuits against public defender offices.

Bunton is among those who think this is a good thing. His office was formed after hurricane Katrina plunged the state’s public defense system into crisis, and he now thinks it has reached another breaking point.

“I think we are at another one of those moments, another one of those milestones as we move forward and try to create a more fair and just Louisiana,” he adds.

In Virginia, Ruzic hopes his state can head off that kind of crisis before it arrives.

“The way those states got there is because no one paid attention to it. It just got worse and worse until it reached a breaking point, and that’s what we’re trying to avoid,” he says. “We shouldn’t wait for something to break before fixing it. We should be doing maintenance and upkeep, especially when it concerns people’s constitutional rights.”

[Editor's note: The original story gave incorrect information about the number of full-time employees in the Orleans Public Defenders office. It also had incorrect information in a chart about the salaries of Loudoun County, Va., public defenders and prosecutors.]