Gay marriage: Court weighs validity of Prop. 8 ruling by gay judge

Loading...

A federal appeals court in California is set to hear argument Thursday on whether to disqualify a federal judge who ruled that the US Constitution guarantees a right to gay marriage.

Supporters of a ban on same-sex marriage say the ruling should be vacated because the San Francisco-based judge in the case failed to disclose that he was, himself, in a long-term gay relationship and stood to personally benefit from his landmark ruling.

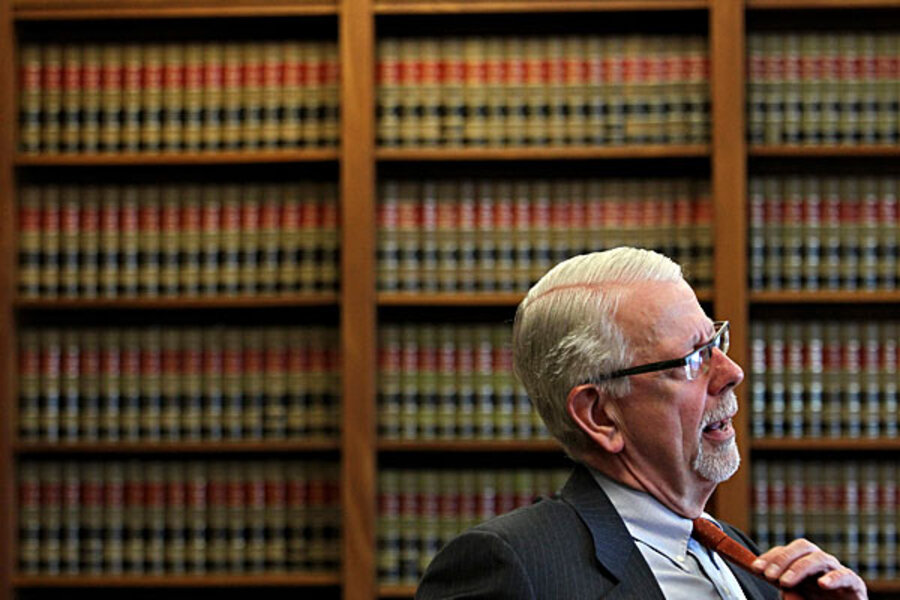

At issue is whether Chief US District Judge Vaughn Walker, who has since retired, should have revealed his relationship to the parties in the litigation prior to the 2010 trial or stepped quietly aside before hearing the case.

The question arises in the context of a legal challenge to California’s Proposition 8, a 2008 ballot initiative that authorized amending the state constitution to limit marriage to a union between one man and one woman.

California voters adopted the ballot initiative with 52 percent in favor and 48 percent opposed. Seven million voters supported the man-woman marriage amendment, 6.4 million opposed it. The action effectively took the issue out of the state courts.

The only remaining legal forum open to gay rights advocates hoping to overturn Proposition 8 was the federal courts.

A gay couple and a lesbian couple filed a civil rights lawsuit claiming Proposition 8 violated equal protection and due process rights guaranteed under the US Constitution. Their case was randomly assigned to Chief Judge Walker.

The judge conducted a 12-day, high-profile trial in January 2010. He announced his decision in August 2010.

Walker ruled that California had no conceivable justification to limit its definition of marriage to a man and a woman while offering identical rights to same-sex couples under domestic partnerships.

Walker invalidated the state constitutional amendment and permanently enjoined California officials from excluding same-sex couples from marriage in the state.

“Plaintiffs do not seek recognition of a new right,” the judge said. “Rather, plaintiffs ask California to recognize their relationships for what they are: marriages.”

Civil and gay rights advocates nationwide hailed Walker as a hero.

Supporters of Proposition 8 appealed Walker’s decision, arguing that the federal judge ignored binding US Supreme Court and appeals court precedents that the traditional man-woman definition of marriage does not violate the US Constitution.

Several months after his ruling, Walker announced his retirement from the bench. During a meeting with reporters he disclosed for the first time to the media that he is gay and that he was in a continuing 10-year relationship.

Lawyers for Proposition 8 advocates seized on the admission and filed a motion that Walker’s earlier decision in the case should be thrown out because he had a personal interest in the outcome of the litigation.

The lawyers are not arguing that Walker should be disqualified because he is gay. Their argument is that Walker’s long-term same-sex relationship created a potential significant personal interest for the judge in the outcome of the litigation.

Should he wish to marry his long-term partner in California, Judge Walker held the power to make it happen.

A federal judge dismissed an initial recusal motion. The issue is now before a three-judge panel of the Ninth US Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco.

The same three judges are also examining Walker’s landmark ruling that the US Constitution protects the right of same-sex couples to marry. But first they must decide whether Walker should have recused himself.

“It is entirely possible – indeed, it is quite likely, according to Plaintiffs themselves – that Judge Walker had an interest in marrying his partner and therefore stood in precisely the same shoes as the Plaintiffs before him,” wrote Washington lawyer Charles Cooper in his brief to the three-judge panel.

Mr. Cooper said judges are required to disclose any relevant facts to prevent even the appearance of impropriety. Walker kept the details of his personal life private until after the trial was completed and his ruling was issued.

Federal law establishes guideposts for judicial recusal. A judge must disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned. Second, a jurist must step aside whenever the judge has an interest that could be substantially affected by the outcome of the proceeding.

The provisions are intended to insulate judges – and the judiciary – not just from clear conflicts of interest but also the appearance that a judge might have a personal stake in the outcome of the case before him.

Lawyers for the gay couples who won their suit argue in their brief to the appeals court that a judge’s sexual orientation and his same-sex relationship do not require a recusal from a case involving same-sex relationships.

“Merely sharing circumstances or characteristics in common with the members of the public who will be affected by a ruling is not a basis for judicial disqualification,” Washington lawyer Theodore Olson wrote in his brief.

“A recusal rule that turns on a minority judge’s subjective desire to enjoy his basic civil rights would effectively disqualify all minority judges,” Mr. Olson said.

Walker’s ruling was not just a routine judicial memo. If upheld by the Ninth Circuit and the US Supreme Court, it would mark a historic turning point in a long-running struggle for gay rights in the US. It would also be a decisive victory in a mounting battle over same-sex marriage and the federal Defense of Marriage Act.

It was also unprecedented in federal appellate jurisprudence.

“Judge Walker’s decision establishing a constitutional right for same-sex couples to have their relationships recognized as marriages conflicts with the judgment of every state and federal appellate court to consider the validity of the traditional opposite-sex definition of marriage under the Federal Constitution – including both the United States Supreme Court and this Court – all of which have upheld that definition,” Cooper wrote in his brief.

Comparisons have been drawn between the same-sex marriage debate and a landmark 1967 US Supreme Court case, Loving v. Virginia, that struck down as unconstitutional a Virginia law banning interracial marriage. Supporters of same-sex marriage say Proposition 8 and similar bans are driven by the same kind of prejudice that kept antimiscegenation laws on the books in Virginia well into the 1960s.

But Cooper mentions Loving v. Virginia for a different reason. He questions whether the judge in the Loving case would have been disqualified from deciding the interracial marriage issue if it became known that the judge “was in a secret 10-year relationship with a woman of a different race whom he planned to marry if his decision invalidating the prohibition was upheld.”

The prospect of such a ruling would create a direct and substantial personal interest in the outcome of the case, which judges are supposed to avoid, Cooper said.

Olson countered that a judge in that situation has no responsibility to step aside. “All citizens have a commensurate interest in equal protection and due process, regardless of whether they happen to be in a position to enjoy a particular civil right in the imminent future,” he wrote.

“The fact that Judge Walker – like more than a million other gay and lesbian Californians – might have an interest in equal availability of the fundamental right to marry cannot require recusal,” Olson wrote.

In addition to the recusal issue, the Ninth Circuit panel will also hear argument on Thursday over whether video tapes of the Proposition 8 trial conducted by Walker should be made public.

Proposition 8 proponents objected to televising the federal court case, citing aggressive tactics, including threats made by some gay-rights activists against those supporting the same-sex marriage ban in California.