NATO summit puts Ukraine’s ambitions on hold, but G7 offers hope

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

For Ukraine, this week’s NATO summit was both disappointing and encouraging, a reality check and a boon to national aspirations and long-term security prospects – part cold shower, part warm bath.

The dose of realism came when the 31-nation, U.S.-led defense alliance declined to formally invite Ukraine to join the club – instead offering in a communiqué Tuesday that NATO “will be in a position to extend an invitation to Ukraine to join the Alliance when Allies agree and conditions are met.”

That clumsy wording infuriated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who in the run-up to the summit in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius, had lobbied NATO members for an invitation and timetable for joining the alliance. Many Eastern European members concluded with Mr. Zelenskyy that the statement was only slightly more encouraging than one issued at NATO’s 2008 summit in Bucharest, Romania.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe competing interests at this week’s NATO summit in Lithuania seemed to play out without diplomatic cover or subtlety. The biggest challenge is simply framed: How could the West support Ukraine without overcommitting?

But on Wednesday, things brightened considerably when the Group of Seven leading industrialized nations – six of which are NATO members – declared on the summit’s sidelines their “unwavering” support for Ukraine. They pledged to extend bilateral security assurances to Kyiv aimed at building a strong and deterrent national defense.

It was the first time the G7 – set up in 1973 to address global economic issues – had committed to defense cooperation with the aim of enhancing another country’s security capabilities.

As such it was a clear signal to Russian President Vladimir Putin, some regional analysts say, that henceforth Western powers consider Ukraine – whether or not formally invited at this summit to join NATO – a member of the community of Western countries.

“The cruel takeaway [of the week’s events] for Putin has to be that a lot of countries want to join NATO, and not that many want to join” with Russia in any security arrangements, says Matthias Matthijs, senior fellow for Europe at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington.

Noting that the internal NATO debate on Ukraine membership is “mostly about speed and not about direction,” he adds, “It does look like Ukraine is lost to Russia” for any kind of future security relationship – a dramatic turn of events for the Russian leader from just over a year ago.

Ukraine’s broader aspirations

Russia was quick to blast the West’s pledge on security assurances to Ukraine, warning in a Kremlin statement Wednesday that the move was a “dangerous mistake” that would threaten Russian and European security alike.

U.S. officials were not shy about describing the security assurances as a clear message to Russia that the West’s commitments to Ukraine are not losing steam, contrary to what some Kremlin insiders have said Mr. Putin has been expecting.

“This multilateral declaration will send a significant signal to Russia that time is not on its side,” said Amanda Sloat, the White House National Security Council senior director for Europe, at a briefing with journalists in Vilnius Wednesday.

The United States and other G7 countries are committing “to help Ukraine build a military ... capable of defending [itself] now and deterring Russian aggression in the future,” she said.

Moreover, she said the commitments will help Ukraine build “a strong and stable economy and ... advance the reform agenda to support the good governance necessary to advance Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations” – a reference to Ukraine’s bids to join both NATO and the European Union.

For some international security analysts, the G7 declaration with its commitment to provide Ukraine with security assurances was ironically the high note that saved the NATO summit from coming off as a disappointment. Just a day earlier, many were interpreting NATO’s communiqué as ambiguous and suggesting that Ukraine membership might never come.

The NATO communiqué “offers Ukraine something, but not much,” says Benjamin Friedman, policy director at Defense Priorities, a Washington think tank advocating a realist foreign policy. “Ukraine is still in the gray zone [where] the goal is always moving away from you to the horizon.”

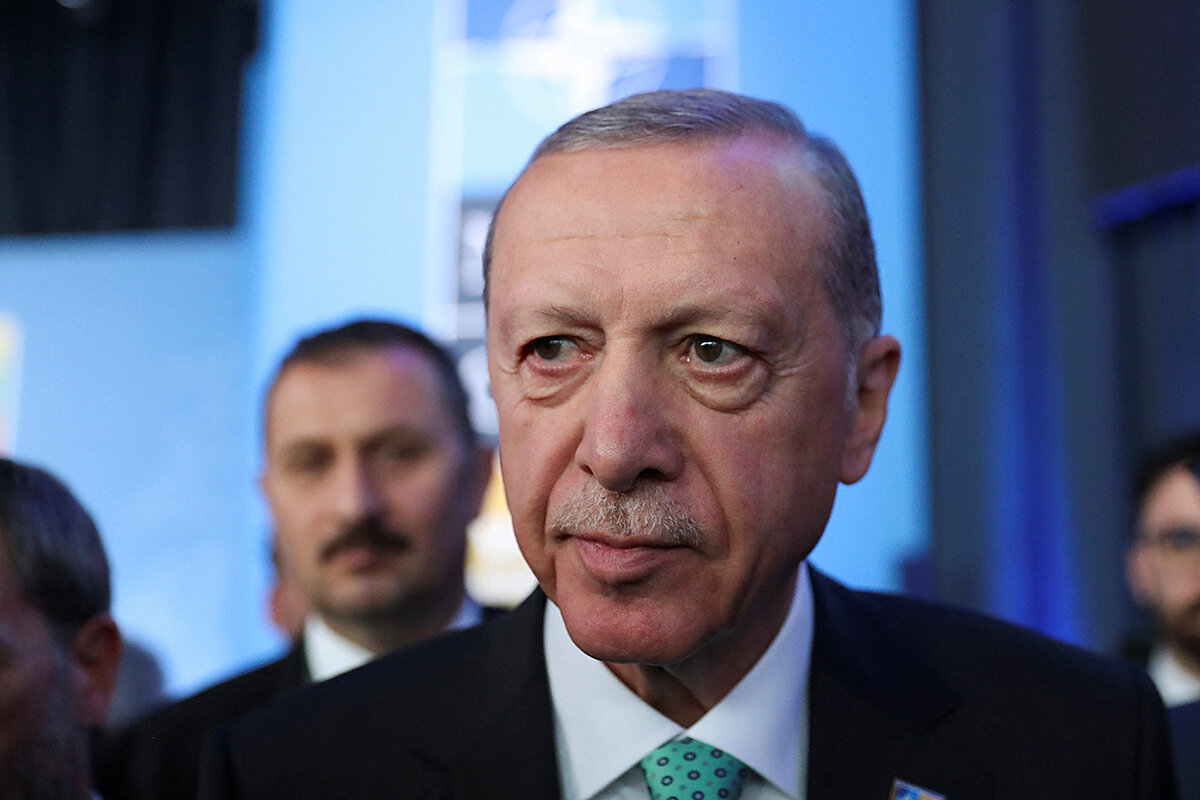

But the Vilnius gathering was not only about Ukraine. Others note that the summit was also the venue where Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan came out of the cold concerning his relations with the alliance – and to some degree with the U.S.

After standing firm for months in opposition to Sweden’s accession to NATO, Mr. Erdoğan surprised everyone by abruptly lifting Turkish opposition to Swedish membership.

What changed? “Part of this was the F-16s,” the fighter jets Turkey desperately wants to buy from the U.S., says Steven Cook, senior fellow for Middle East and Africa studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington.

But another part is that “Erdoğan did overplay his hand,” Mr. Cook adds. The Turkish leader is always going to pursue an “independent foreign policy,” he says, but not at the cost of severing Turkey’s valuable relationships.

“U.S. and European diplomats made it very clear – he was at risk of further damaging relations with the U.S., NATO, and Europe,” he says. “The result was the change in 24 hours.”

The “Israel model”

For others, the Vilnius summit will go down as the marker for the alliance’s power shift to Eastern Europe and those countries – the Baltics, Poland, the Nordic countries – most threatened by Russia’s revanchist vision under Mr. Putin.

Indeed, French President Emmanuel Macron’s shift from the go-slow-on-Ukraine-NATO-membership camp – led by the U.S. and Germany – to supporting an invitation to join is a reflection, some analysts say, of his ambitions for French leadership of a Europe that has shifted east.

For weeks before the NATO summit, analysts and U.S. officials had suggested that the big takeaway from Vilnius might be some form of security assurances for Ukraine other than NATO membership – especially given President Joe Biden’s position that Ukraine membership was off the table as long as the war rages.

And the model Ukraine could aspire to, some said, would be U.S. security commitments to Israel.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, Mr. Zelenskyy has had to regularly go hat in hand to the U.S. and other backers for the arms and funding needed to fend off Russia and to try to push it out of the fifth of Ukrainian territory that it occupies.

In effect, Ukraine has no certainty it will have the resources it needs to continue fighting next month, let alone next year. Planning and developing a long-term defense strategy becomes impossible.

Enter the “Israel model.” Since the 1970s, the U.S. has developed specific written security funding, equipping, and training guarantees that have allowed Israel to confidently build a national defense. Moreover, the assurances have sent a clear signal to regional adversaries that Israel’s defense is backed by its long-term security relationship with the U.S.

“Entrapment risks”

The G7’s declaration on a plan for Ukraine security assurances includes many elements of the Israel model. But some analysts caution that a crucial element in Israel’s relationship with the U.S. could be missing for Ukraine: strong and unfaltering bipartisan support.

“U.S. politics are the reason Israel has as close to a true security commitment [from the U.S.] as anyone,” says Mr. Friedman of Defense Priorities. Congress would have to “sign off on” regular defense appropriations for Ukraine, and he doesn’t see the same level of support for Ukraine as for Israel.

Indeed, a small but growing group of Republican members of Congress favors slashing U.S. military funding to Ukraine.

Some who see clear advantages to offering Ukraine an Israel model of security assurances also warn of a key downside: It could, they say, inadvertently leave the U.S. facilitating policies it doesn’t support.

In a recent analysis of an Israel model of security assurances for Ukraine, Emma Ashford and Kelly Grieco of Washington’s Stimson Center speak of “entrapment risks,” in which sustained security support enables policies and actions “untethered from U.S. national interests.”

In the case of Israel, they note, unquestioned U.S. security support has left Washington impotent in the face of actions it opposes, such as continued West Bank settlement expansion.

Some worry that, just as stating that “Ukraine can only enter NATO once the war ends” provides Mr. Putin with an incentive to keep the war going, security assurances to Ukraine could also end up prolonging the war.

The prospect of long-term funding and other military commitments could convince Ukraine it need not come to the negotiating table, Mr. Friedman says.

“I’m OK with arms and money to Ukraine,” he says, “but I’m afraid anything more is just leading them down a false path.”