'Welfare-voter' spat in Massachusetts part of larger political duel

Loading...

| Boston

A controversy over voter registration in Massachusetts is serving up a reminder: Election 2012 revolves not just around a messaging war but also around efforts by both parties to affect voter turnout.

Republican Sen. Scott Brown has complained that, in an unusual move, state officials have used taxpayer money to mail voter-registration forms to welfare recipients. The move is such a blatant effort to boost Democratic support, he argues, that his Senate-race opponent should pick up the mass-mailing tab.

Officials for the state, politically dominated by Democrats, say the mailing to welfare recipients was a logical response to legal pressure. The move is part of an interim settlement with plaintiffs who argue that the state has failed to comply with a 1993 federal law designed to ensure better voting access for Americans – including the opportunity to register while renewing a driver's license or signing up for welfare.

A lot of potential votes are at stake.

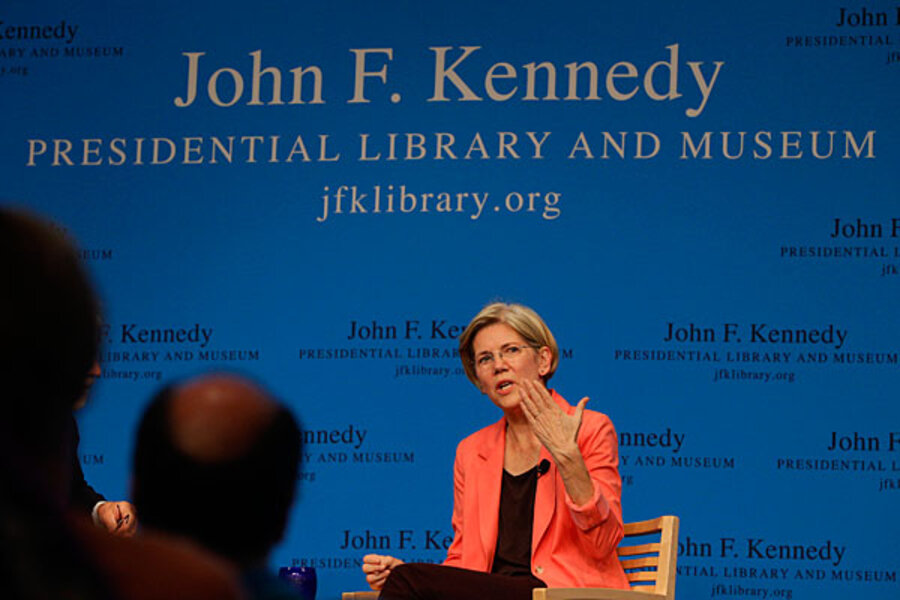

The mailing went out to nearly half a million Massachusetts residents, which the Brown campaign characterizes as about one-third the number of votes that will end up winning the Senate race between Senator Brown and his rival, Elizabeth Warren. Currently the race is shaping up as one of the tightest and most closely watched in the nationwide battle for control of the US Senate.

Although Brown has cast the state's actions as shocking, and although Democrats have professed their own shock that he would see anything to criticize, political analysts say the tiff follows a well-worn pattern.

"This is something that fits into a larger battle between the left and right over our voter rules," says Richard Hasen, author of a new book on the subject, called "The Voting Wars."

"What you see are liberal groups ... looking to enforce the pro-voter provisions of the National Voter Registration Act," the 1993 law also often known as the motor-voter act, say Mr. Hasen, who is a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine. Conservatives, by contrast, tend to seek enforcement actions that purge voter rolls, such as weeding out people who are ineligible because they aren't US citizens.

Republicans have stirred Democratic anger in some states, for instance, with new laws requiring photo ID at the voting booth.

This pattern reflects both political calculations and ideological differences between the parties. In general, political analysts say Democratic candidates for office get a leg up when voter rolls are enlarged.

The results of one new survey, for example, suggest that President Obama could coast to reelection if he could generate higher turnout among Americans who are unlikely to vote – not because they aren't eligible but because they feel too busy or apathetic.

Beyond calculations of political gain, the "voting wars" that Hasen tracks are also about philosophical differences between the parties.

Democrats tend to emphasize the political positives of getting more eligible Americans to vote, while Republicans emphasize the civic virtue of minimizing vote fraud. Hasen sees room for the US to improve on both fronts, compared with other advanced nations that achieve both higher turnout and more careful management of the process.

A central player in the Massachusetts controversy is the political advocacy group Demos, based in New York. It provided legal representation that allowed plaintiffs in Massachusetts to sue the state this year over alleged violations of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA).

In recent statements, Brown has pointed out that the action by Demos comes at a time when the group's lead trustee is the daughter of opponent Ms. Warren.

Other facts have also aroused conservative criticism. Demos is also pursuing voter-registration cases in Pennsylvania and Nevada, considered important "swing states" in the presidential race. And the office of attorney general in Massachusetts, a central player in agreeing to the interim settlement of Demos's litigation, is currently occupied by Martha Coakley, who was the surprise loser when Brown won his Senate seat in a 2010 special election.

Lisa Danetz, senior counsel at Demos, says the group's actions are explained by its public-service mission, not by efforts to sway particular political outcomes this year.

Warren's daughter, Demos trustee Amelia Warren Tiyagi, "has had no role whatsoever in the [motor-voter] litigation generally or the Massachusetts case specifically," Ms. Danetz says.

And Demos has targeted many states in recent years, resulting in settlements or legal victories in a number of states. Those include Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, New Mexico, Ohio, and Virginia.

Several of those states are important presidential swing states, but Danetz describes the group's priorities in a different way, ticking off how Demos and partner organizations have worked in states that rank near the bottom when it comes to enrolling new voters at public-assistance offices. The Department of Justice has also pursued litigation in some states.

Danetz says Demos pushed hard for Massachusetts to do a mass mailing, because in this case (unlike others) an election is looming with no other timely form of redress available.

The focus on welfare recipients, viewed as likely Democratic voters, is another source of controversy. Republicans note that the NVRA calls for strong efforts to enroll voters at motor-vehicle licensing departments and at military recruiting centers, not just at welfare agencies.

Liberal groups defend putting a high priority on enrollment efforts aimed at the poor or disabled. "We are concerned with making sure that as many voices are heard in the political process as possible," and low-income people tend to be under-represented in voting booths, Danetz says.

Hasen says many states fail to comply with the NVRA's call for enhanced opportunities to register. When pressed by lawsuits, many seek to reach a settlement, as Massachusetts is doing.