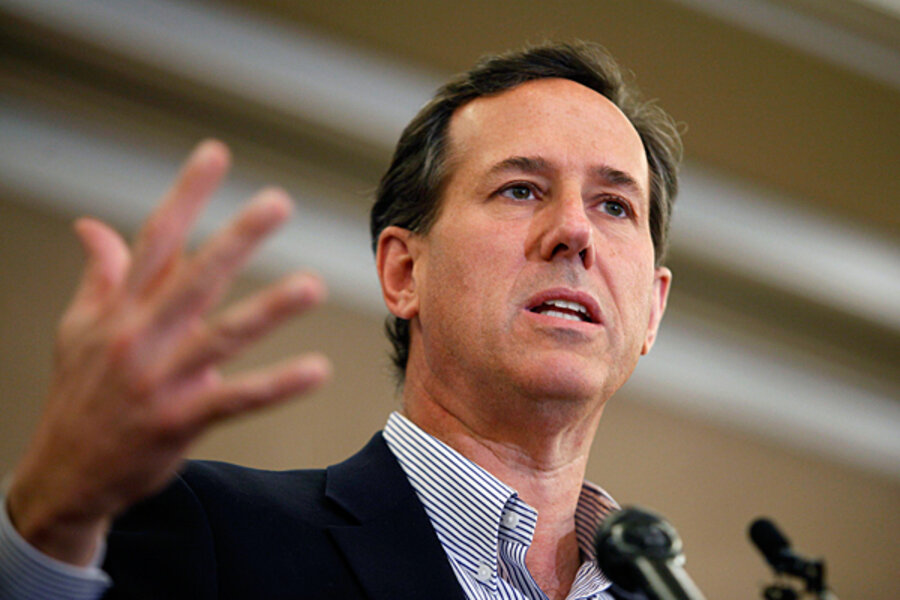

Does it help Rick Santorum to slam JFK on religion's role in politics?

Loading...

Rick Santorum's latest foe, rhetorically at least, is a politician from half a century ago: John Kennedy.

The Republican candidate for president has loudly condemned a 1960 speech in which then-Senator Kennedy outlined a limited role for religion in politics.

The cross-generational dust-up is serving as a reminder of how American attitudes about the interplay of religion and politics have evolved since President Kennedy's time.

Back then, the Democratic presidential contender's speech served to soften widespread public worries that a Roman Catholic president might be beholden to the views of a church hierarchy. Today, former Senator Santorum sees points to be scored by defending the role of faith in public life (he is also Catholic), not downplaying it.

Here's Santorum in February 2012:

“I don’t believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute. The idea that the church can have no influence or no involvement in the operation of the state is absolutely antithetical to the objectives and vision of our country,” said Santorum in a Sunday interview on ABC News. “This is the First Amendment. The First Amendment says the free exercise of religion."

Here's Kennedy in September 1960:

"I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote," Kennedy said in a speech at the Greater Houston Ministerial Association.

Kennedy's comments helped his candidacy. Today, Santorum's very different comments may also work in his favor – in the Republican primary at least.

"Back in 1960, John Kennedy had to stress the distance between public life and religion," says Robert Schmuhl, a Notre Dame University expert on US politics, in an e-mail interview from London, where he is teaching this spring. For Santorum, "catering to social conservatives is one way he can appeal to an important Republican Party constituency in the primaries and caucuses."

Public concerns about whether a Catholic would make a dangerous president, while they may not have disappeared, have faded. By contrast, two-thirds of Americans today see religion as "losing influence" in US life, rather than gaining, according to a 2010 poll by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. And many, especially among Republicans, see that as a problem.

When Kennedy was seeking the presidency, only a small minority of Americans felt that religion was "losing its influence," according to Gallup polling at the time.

The changes over the past five decades include a confluence of social and political forces. America has remained deeply religious, compared with other industrialized democracies. Yet the perception that religion is losing influence has been matched by the rise of what political analysts David Domke and Kevin Coe have called a "God strategy" in US politics.

Republican politicians, and to a lesser extent Democratic ones as well, have become more vocal about their religious faith – and have enhanced their connection with many voters as a result. They may not quite be kneeling, Tim Tebow-style, before each speech. But Mr. Domke and Mr. Coe argue in their 2008 book that Kennedy's speech conveyed "a welcome message then" that would be "almost unimaginable today."

Polls show that Americans want their leaders to be people with strong religious faith, says Greg Smith, a senior researcher at the Pew Forum.

At the same time, it's important not to overplay the cultural gap between today and 1960.

Kennedy didn't disavow all role for religion in public life, as Santorum's comments intimated. He erroneously accused Kennedy of saying "faith is not allowed in the public square."

Although Kennedy talked about "absolute" separation, his speech implied a specific definition of this in practice: No church would be dictating his decisions, and he would seek the best interest of a nation in which "no religious body seeks to impose its will directly or indirectly upon the general populace."

Kennedy added this: "nor do I intend to disavow either my views or my church in order to win this election," and he ended the speech, "so help me God."

Today, as in the 1960s, many Americans share some of the concerns Kennedy spoke to. Mr. Smith cites a 2010 Pew survey finding that 52 percent of Americans, essentially the same share of Americans as in 1968 (in a Gallup poll), say that churches should stay out of politics, rather than push their views in the political arena.

Americans "want to see that kind of influence of religious values" on their leaders, Smith says. "At the same time there's a line at which they don't want to see too much mingling of religious influence in politics."

John Green, a political scientist who tracks the role of religion, says that in 1960, the religious divide in politics was among groups such as Catholics and Protestants. Today, the divide has become more about the preferred level of religiosity in a candidate, says Mr. Green, at the University of Akron in Ohio.

Santorum appeals to many voters who favor a strong level of religiosity. That's a sizable share of Republican voters in the primary races, but a smaller share of the swing voters who would become crucial to Republican hopes in the general election.