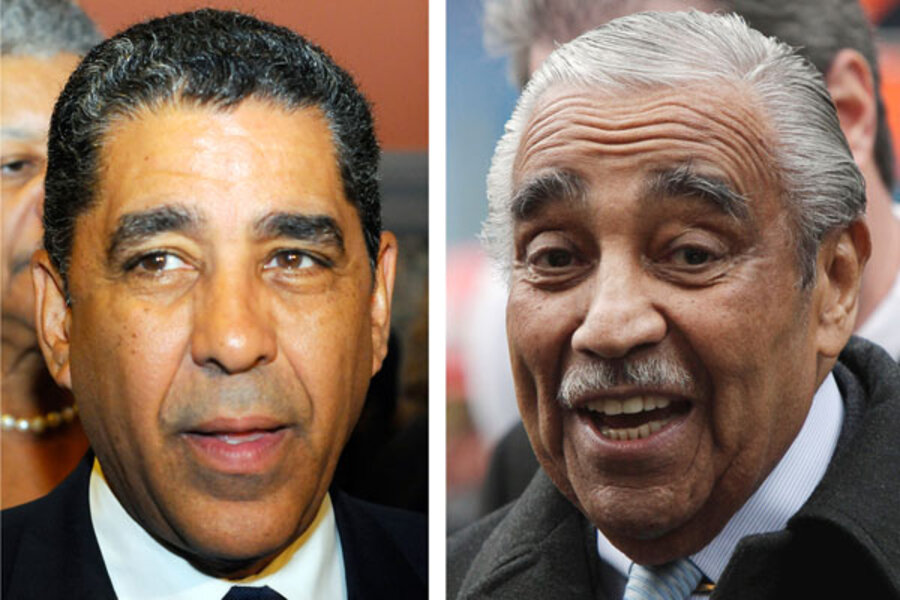

Could Charles Rangel get 'Cantored'? Powerful Democrat faces primary fight

Loading...

| New York

One of the most powerful liberal Democrats in the House, New York Rep. Charles Rangel, who has held his Harlem seat since 1971, is in the middle of a fierce primary battle.

The race is one of the few around the country that pits two strong Democratic challengers against each other in a primary, underscoring a stark difference between the current Republican and Democratic Parties.

Last week, when tea party-backed David Brat upset House majority leader Eric Cantor (R) of Virginia, the win was seen as part of the nationwide conservative insurgency against the Republican establishment, sending shock waves through the party.

Should state Sen. Adriano Espaillat defeat Congressman Rangel in their June 24 primary, the win would likely be seen for what it is – a product of shifting local politics in New York's 13th Congressional District.

Curiously, Espaillat is hitting Rangel with some of the same charges that Mr. Brat used to defeat Congressman Cantor, suggesting that Rangel is beholden to big business. Citibank, Espaillat notes, is the 22-term incumbent's second-largest source of campaign contributions, according to campaign finance reports. And Rangel voted to roll back a key part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reforms, which required banks to move risky derivative trading into separate business units that would not be insured by taxpayers. The bill was mostly written by Citibank, according to The New York Times.

Yet Rangel’s primary troubles have less to do with an ideological insurgency from the remnants of Occupy Wall Street or the far left than from the changing face of the district he’s represented for more than 43 years, observers say. This race is really more a case of “all politics is local” than a sign of a simmering unrest in the Democratic Party.

“I’m not sure there’s an ideological component to the race at all,” says Ken Sherrill, professor emeritus of political science at Hunter College in Manhattan. “I think that while people don’t like to say there’s a racial and ethnic component to it, there probably is.”

Northern Manhattan has a sizable Dominican population, and Espaillat, who was born in the Dominican Republic before immigrating to New York at a young age, has long been popular among his district’s Latino voters.

After the 2010 census, Rangel’s Harlem district was redrawn to include a swath of the Bronx, which also has a concentration of Latino voters. In 2012, Rangel beat Espaillat by less than 1,000 votes. This year, he's feeling the heat again.

“Just what the heck has he actually done besides saying he’s a Dominican?” Rangel said during a debate in early June.

“To come here and spew division is not becoming of you and your title as a congressman,” Espaillat shot back. “You should really apologize.”

After redistricting, the 13th Dictrict is now 55 percent Latino and only 27 percent black. According to a New York Times/NY1/Siena College Poll, Espaillat has a 55 to 25 percent lead among Latino voters, while Rangel is polling 68 percent of black voters to only 5 percent for Espaillat. Overall, however, Rangel still outpolls Espaillat 41 to 32 percent.

But the octogenarian congressman has had other troubles. A number of ethics issues forced him to step down from his powerful position as the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and led to an official House censure.

Despite his attacks on Rangel’s ties to the banking industry, Espaillat is no insurgent. As the ranking member of the state Senate Housing, Construction and Community Development Committee, as well as the chair of the Senate Latino Caucus, the Dominican senator has deep political ties within the Manhattan Democratic establishment, and has garnered a number of key labor union endorsements, including the powerful teacher’s union.

“There’s often a political calculus in these endorsements, in that Espaillat’s candidacy may represent the future shape of New York politics, and that one is wiser to be on the prevailing side,” says Professor Sherill, “But I don’t think this is ideological; I don’t think there are significant policy differences. This is more about character and generational and demographic differences....”

Ironically, Brat's win in Virginia might have been no different – the product of local, not national issues. What differs is the party narrative surrounding it.

“They voted Cantor out because they didn’t like him,” Sherrill says. “They voted Cantor out for ignoring the district, and because it turned out that he had no friends in his district, which matters a lot in politics.”