‘Good morning, sweet girl’: A day in the life of an online teacher

Loading...

| New York

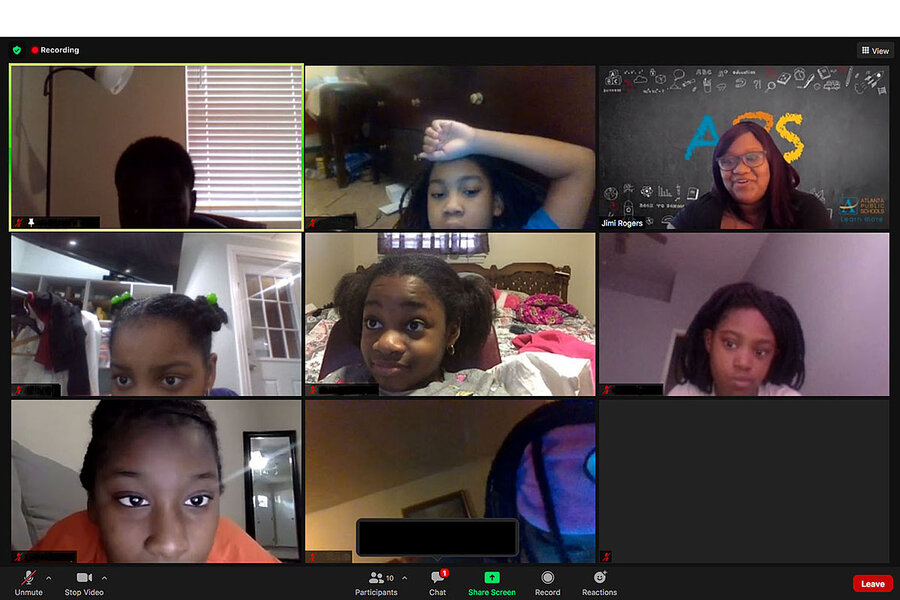

The third graders lean in to type, turning the Zoom classroom into a mosaic of mostly foreheads. Answering equations in an app monitored by their teacher, some L.O. Kimberly Elementary School scholars mouth along as their fingers find the keys.

A math test looms tomorrow and it’s time to review. Jimi’ Rogers knows the stakes: Of the dozen students in her virtual class, five are struggling to meet math benchmarks. Yet she stays calm and encouraging this Tuesday morning as she asks them to add 349 and 145 – and show how they arrived at the answer.

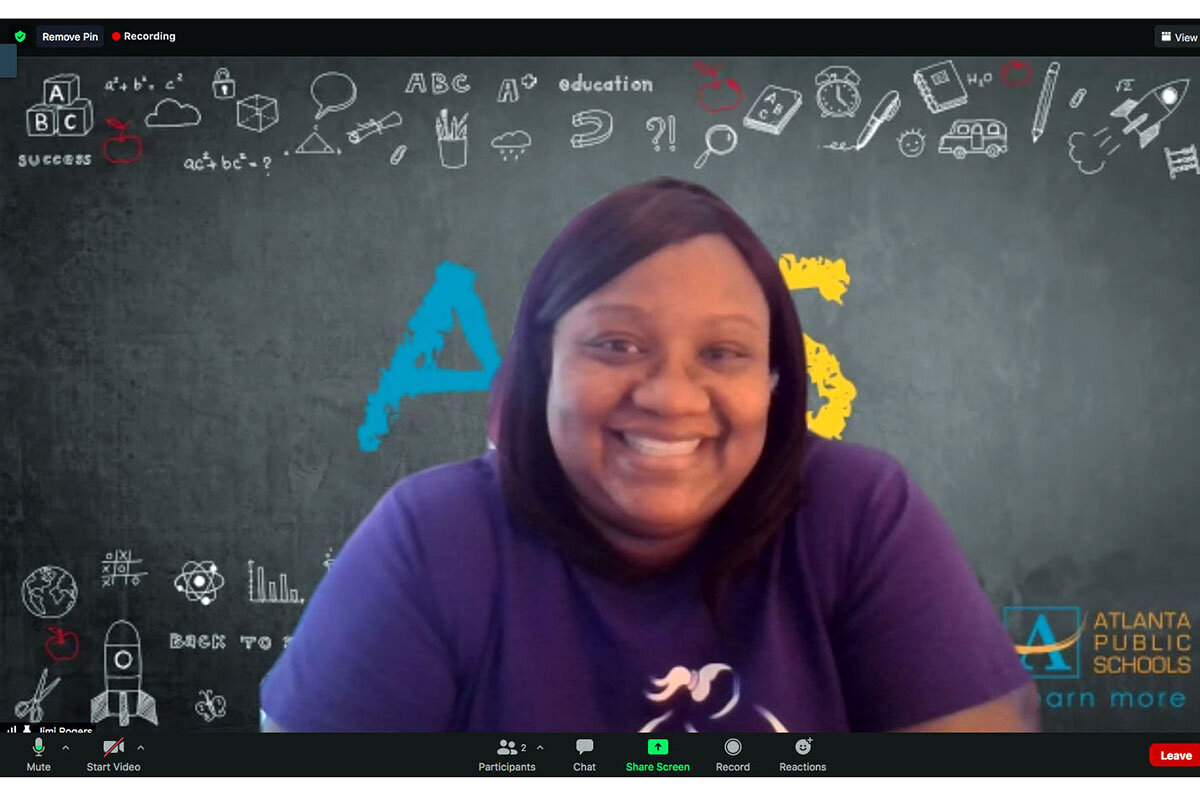

“I really appreciate the hard work,” Ms. Rogers tells them. Her home office is hidden by a Zoom background, a digital chalkboard with Atlanta Public Schools’ logo. “I’ll give you about four minutes to do this, OK?”

Before she utters “OK,” a student has typed in the chat: my dog step on my keyborad

Another girl unmutes herself to announce she has a notebook and pencil. “Very good,” Ms. Rogers patiently replies, as the girl dangles a metallic-gold pencil pouch for the camera.

The first student updates in the chat that the dog made a mess on the living room floor.

“I don’t need to know about that, honey,” the teacher intones. “Handle that, please.”

The pandemic has turned remote teachers like Ms. Rogers into air traffic controllers of virtual spaces – upended by technical snags and the randomness of home life. Teachers like her, who are working more hours than before, are keenly aware of potential learning loss and other fallout from unequal access to school.

A view into Ms. Rogers’ “classroom” reveals that keeping pupils on track means constantly adapting to an environment where so much is out of a teacher’s control. And yet, for every head that tilts in frustration, there are moments of mastery, too. Inspired by her students, Ms. Rogers focuses on what she can control: her own preparation and poise.

“We teachers are doing the best that we can,” she says.

School days for Ms. Rogers often start with a 4:45 a.m. wakeup. She drives to the gym for the treadmill, followed by a peppermint tea. She refreshes her devices next, resetting her router and restarting her computer to ward off digital glitches before she logs into her classroom at 8 a.m.

“Good morning, sweet girl,” she greets a student whose camera stays off for most of the day.

Ms. Rogers has only met four of her pupils in person through home visits and tutoring at the school. She laments: “I’m a hugger, and I can’t hug them right now.”

Fresh respect

Beyond classroom management, there’s the long-term worry of kids falling behind in new learning formats. Like thousands of her colleagues across the country, Ms. Rogers had little choice but to adapt to digital teaching.

“Being honest, there’s a lot more I could do if we were face-to-face,” she says.

In her eighth year of teaching and first at Kimberly Elementary, she says preparing virtual lessons – from creating slides to catching up kids who fall behind – takes 10 to 15 hours a week outside her normal school day. That’s more work than previous years, in part because she’s adjusting to a new school.

“You need to be on-point so that they can go out into the world and change the world, like your teachers did for you,” says the Georgia native, whose own third grade teacher sparked her love of reading through “The Chronicles of Narnia.”

The extra planning takes a personal toll. Ms. Rogers’ fiancé has watched her preparation eat into their weekends. Since online classes began, “I have a whole other level of respect for her,” he says.

Outside of class, Ms. Rogers regularly reaches out to students and parents to make sure they’re OK. She arrived at a student’s home with food from KFC this fall following a death in the child’s family.

Trying to bridge the digital distance can be frustrating, she says; three-fourths of her class typically shows up. Since Atlanta school buildings closed in March, 90% of Kimberly Elementary students have received Chromebooks or iPads, and the district has also chipped in hotspots. Still, tech issues linger.

Daily surprises scatter focus – faulty browsers, sibling cameos, the occasional frantic dog tail in the corner of a screen.

During a recent writing lesson, an adult’s shoulder hovers in one pupil’s screen. “Scholars, again, this is your own work,” Ms. Rogers says, then fires off a private message with her sleek red nails.

Her favorite virtual moment arrived during a November math class as she taught a rounding lesson. When she encouraged her students to unmute, the result was “exciting,” she says. Everyone wanted to participate.

“Finally, I feel like I’m getting through,” she recalls thinking. “These kids and I are now building this safe space where it’s OK for them to talk in a virtual environment.”

During language arts, she asks a quiet boy to read aloud a page from a French folktale that will test his group’s comprehension. Rontavius smiles, and Ms. Rogers returns the grin when he begins a couple decibels above a whisper.

“‘I see,’ said the snail. ‘And you have proof that the Earth is round?’” he reads smoothly.

The digital book font is small, so Ms. Rogers tries to zoom in. But her webpage turns blank as it buffers – computer purgatory. His voice continues undeterred, though his forehead will freeze in profile before class ends. Rontavius finishes the page and wipes his brow in apparent relief.

“All right, very good,” Ms. Rogers tells him. “Although I don’t know what just happened.”

She’s used to such glitches and moves on. Plus, Ms. Rogers says the students model her behavior: “If they know that I’m OK and I’m upbeat, they will do the same thing.”

Ms. Rogers strives for perfection, but pandemic demands have taught her to be gentler with herself. She says she’s learning to accept that teachers make mistakes.

“Before, I was like: You don’t have the room to make a mistake, because you’re teaching the future,” she says.

During a recent math class, Ms. Rogers admitted to the class she’d misread a multistep word problem. Then a student typed her a love note into the Zoom chat for all to see.

“That made me feel really good today,” Ms. Rogers says after class. She may not always have their attention, but she has their respect.

“Locus of control”

Ongoing research points to greater learning loss in math than reading. Test data from one study of 4.4 million U.S. students suggest that the pandemic pivot to online learning has meant a “moderate” drop in students’ math skills, though the sample underrepresents marginalized students. Principal Joseph L. Salley says some learning loss is likely during the pandemic at the majority-Black, 336-student school; but he tries to calm staff nerves.

For teachers, he says, “it’s all about focusing on what’s in your locus of control.”

While the school is still reviewing benchmark assessments to determine math and reading growth at the time of writing, the principal praises Ms. Rogers’ preparation and embrace of new technology. She uses breakout rooms and interactive slides on Google Jamboard, for instance, where students cut and paste units of measure to solve math problems. At the end of class, they submit virtual “exit tickets” that gauge their grasp of a lesson.

“Despite the pandemic, she hasn’t skipped a beat!” he says.

Schools with the highest shares of minority students and poverty have been less prone to offer in-person instruction during the pandemic, according to Rand Corp. research (75% of students are eligible for free or reduced lunch at Kimberly Elementary). The district has announced plans to phase into in-person classes after winter break, and Mr. Salley is preparing new safety protocols.

As much as Ms. Rogers supports her school leadership – and loves her “magnificent 12” – she says her feelings are mixed. With an underlying health condition, she’s wary of catching the virus; that’s why she heads to the gym at unpopular hours.

“I have to work … I’m going to pray about it,” says Ms. Rogers, a Baptist.

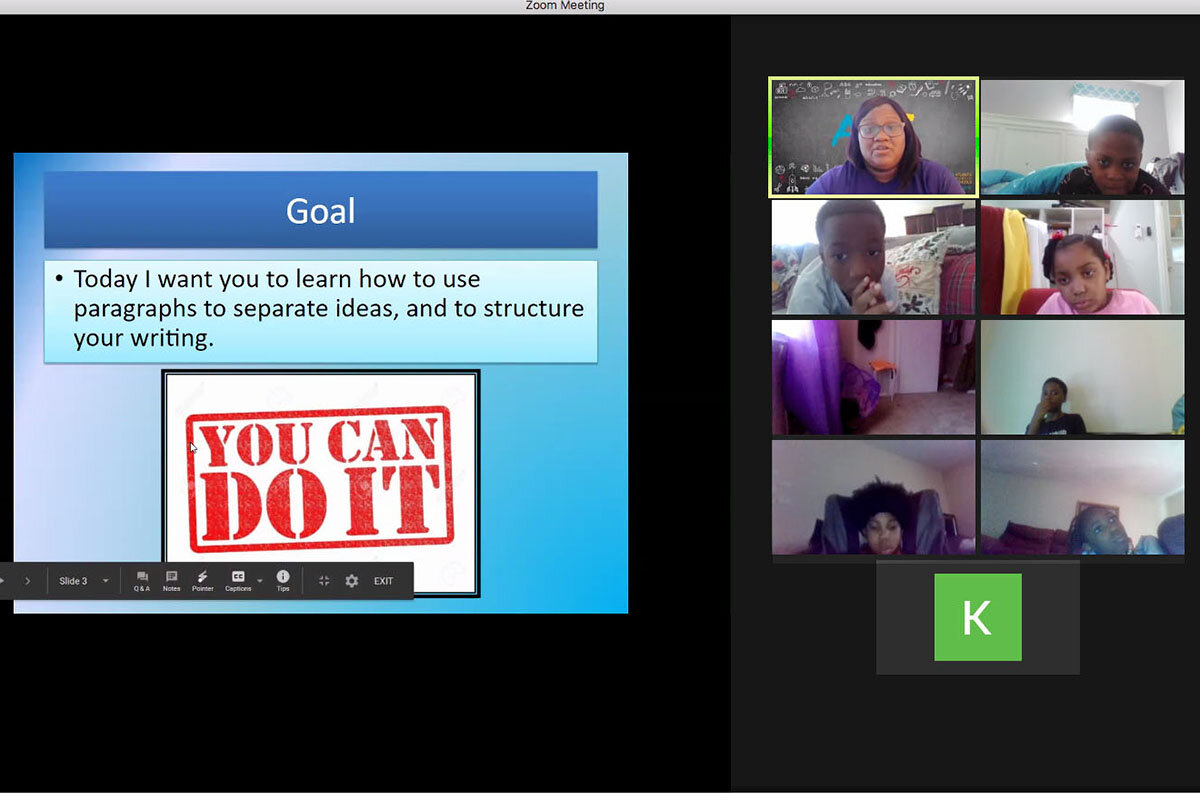

In the meantime, she takes one day at a time. During Tuesday afternoon’s introduction to the concept of the paragraph, she asks them to post what they know in the chat, reminding them there are no wrong answers.

Responses trickle in. She sees that only the girls have chimed in.

“I got nothing from my boys, and it breaks my heart!” she proclaims. The young ladies take turns typing out an intervention.

One writes: try your best boys its ok if you are wrong some times you make mistaks

It’s ultimately not enough to rouse their peers, but Ms. Rogers keeps the class moving. She’s generous with praise, even if their thinking is unconventional.

“Nyla, can I show yours to the class for a second?” she asks. Nyla nods in earnest, jangling her long black braids.

Ms. Rogers presents Nyla’s Google doc, a composition about frogs. The twist: The block of text is typed out in six rainbow colors – red through indigo – shifting hue with topics.

“This is an excellent way to spread out your ideas,” Ms. Rogers gushes. Nyla leans in.

Ms. Rogers starts her cursor at the top of the text and indents where the colors change. The rainbow cascades down the page as paragraphs appear.

It’s already 2 o’clock. In a moment, Ms. Rogers’ scholars will disappear with a click.

Their screens briefly blur as they wave.

Editor’s note: Ms. Rogers’ fiancé’s name has been removed due to security concerns.