Miramonte sex abuse: Schools facing Catholic Church-like wave of scandal?

Loading...

| Los Angeles

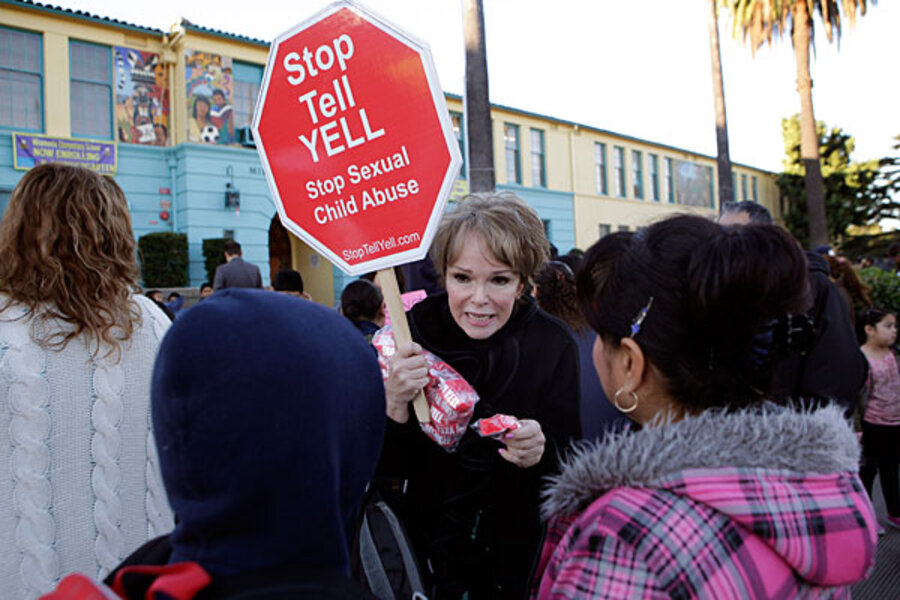

The reopening of an investigation into teacher misconduct at a high school in Hollywood and the initiation of another in Pacoima – both in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) – is leading to concerns that the lewd behavior uncovered at Miramonte Elementary School might be more widespread than thought.

Noting that sex-abuse incidents have also recently hit universities, including Penn State and Syracuse, activists and analysts are suggesting that schools could be facing a test similar to the one endured by the Roman Catholic Church, when sexual abuse allegations were no longer able to be swept under the rug.

“There is a lot more of this going on than we have any idea about,” says Charol Shakeshaft, a professor in the school of education at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

She was hired by the US Departments of Education and Justice in 2004 to conduct the only national study of the incidence of teacher sexual misconduct with students. The report found that some 7 percent of the 4,000 sampled schoolchildren had experienced sexually inappropriate behavior by teachers or administrators. That “translates into about 3.5 million children,” she points out.

Considering that, on average, only 9 to 11 percent of all sexually abused children actually report the abuse, the number could be much higher, says Professor Shakeshaft.

In the 10 days prior to Jan. 30, when the scandal at Miramonte went national, there were no reports of sexual misbehavior between district employees and students, an LAUSD spokesperson reports. Between Jan. 31 and Feb. 3, however, there were nine such reports from schools to the district office.

This does not necessarily mean an uptick in abuse, points out Mark Sudderth, a Texas attorney whose firm specializes in sexual-abuse cases nationally. Rather, the exposure of abuse helps other victims feel more confident about coming forward, he says.

“The media plays a key role here,” he says via e-mail. Broad reporting of the incidents gives parents and educators greater awareness of the potential for harm and leads to greater awareness of signs that abuse may be occurring.

“Sadly,” he adds, “I expect that we will continue to learn of more such incidents as more children become aware that they can come forward and report conduct that, at a minimum, makes them uncomfortable.”

Comparisons to the sexual misconduct scandal in the Catholic Church are appropriate, says Terri Miller, president of SESAME, a Nevada-based national advocacy group on behalf of sexually-abused schoolchildren.

The two institutions have much in common, she says, “children trust the adults in those settings, they are encouraged to believe and obey.”

The biggest difference, she says, is “our children are not required to go to church, but they are required to go to school.”

Her all-volunteer, nonprofit organization is backing efforts to change laws that govern how much information employers can obtain about prospective school applicants. She points to the Jeremy Bell Act, sponsored by Rep. Michael Fitzpatrick (R) of Pennsylvania, which would criminalize withholding of any information about prior sexual misconduct by an applicant at a school. It is named for a 12-year-old who was drugged an sexually assaulted by his principal on a camping trip.

“This man was passed along by 18 different districts who knew about allegations and never passed the information to the next school,” Ms. Miller says. “This has got to stop.”

In January, the bill was referred to the House Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security.

Many teachers and administrators worry that this new wave of attention to the issue wrongly demonizes the vast majority of educators who are honorable and devoted to their work, says Elizabeth Reilly, professor of educational leadership at the School of Education of Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

She met with 25 doctoral students on Monday – many of whom are principals in the LAUSD. “The keys are transparency and accountability,” she says.

But nearly all training for detecting sexual abuse is geared toward teachers detecting abuse outside the school, not from within it, says Virginia Commonwealth University's Shakeshaft. “Teachers are trained to detect signs of parental abuse, but not teacher abuse,” she says.

There has been some progress, however. “When I began my work, I used to get hate mail from teachers asking why I hate teachers,” she says. “At least that has stopped.”