Lesson of L.A. teacher sex-crime case: Heed children who report abuse

Loading...

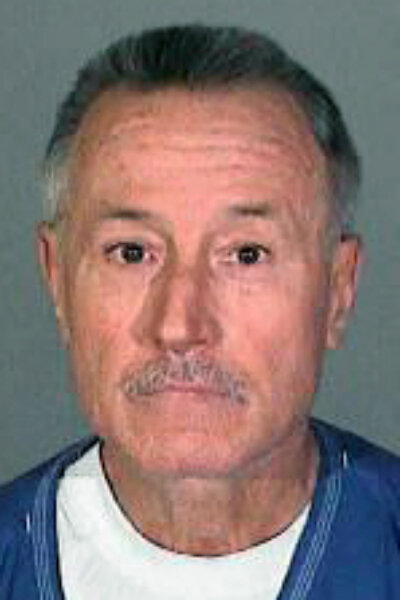

Shocking charges that surfaced this week against Mark Berndt raise questions about how long teachers may be able get away with sexually abusing their students before the law catches up with them.

Students are often afraid to report incidents of abuse, victim advocates say, and when they do, too often their stories are dismissed or don’t lead to officials stopping the educator from abusing again.

“That message can never stop, that children need to be believed,” says Terri Miller, president of Stop Educator Sexual Abuse, Misconduct, and Exploitation, based in Las Vegas. School staff sometimes ignore warning signs or reports “because they don’t want to deal with the … cloud of shame that hangs over a school when these cases come to light,” she says.

Mr. Berndt taught at Miramonte Elementary School in the Los Angeles Unified School District for more than 30 years. He was suspended and resigned in early 2011 when the county sheriff's department began investigating charges that led recently to his arrest on 23 counts of committing lewd acts on children.

Those charges date back to 2005. But the alleged troubling behavior may have started much earlier, authorities say.

In 1994, Berndt was investigated by the sheriff's department, but not prosecuted, for allegedly trying to fondle a 10-year-old girl, the Associated Press reported Thursday afternoon.

Two women also said this week that when they were students of Berndt’s in 1990-91, they told a counselor of behavior in the classroom that implied that he was fondling himself, the Los Angeles Times reports. One of the women said the counselor “told us it’s not very good to make stories up. She said it was our imagination.”

The school district is launching its own investigation into how Berndt’s alleged behavior could have gone on undetected for years. The case came to light when a photo developer called law enforcement officials in late 2010 about incriminating photos, the LA Times reports.

Berndt is accused of blindfolding and gagging students, and making them play a “game” of tasting strange things, including spoonfuls of a substance that police say was his semen.

Berndt was removed from the classroom as soon as the criminal investigation started. But the school district was asked to hold its own investigation only after the criminal probe was complete.

In a Feb. 1 letter, L.A. Unified Superintendent John Deasy wrote: “The District takes each and every reported act of criminal and administrative misconduct seriously, and we will continue to aggressively pursue each case … and initiate the appropriate disciplinary measures.”

While abusers often select and “groom” a young target to trust them until they can get him or her in a private setting, there have been cases of abuse in front of other students. A 2004 report for the US Department of Education mentions a case in which a teacher would call boys up to his desk one at a time to discuss homework, and then would fondle them.

“Every child in the room knew what was happening and students talked about it among themselves. The teacher repeated this behavior for 15 years before one student finally reported to an official who would act,” says the report, prepared by Charol Shakeshaft, now a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, in Richmond.

In 2010, a report by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) detailed cases of abusive educators moving from state to state and committing new offenses – even sometimes after being convicted of sexual abuse. State laws requiring background checks or reporting of sexual misconduct in schools vary widely.

There have been some small signs of progress. A 2011 law in Missouri may be the first to really try to stop the phenomenon. Known as the Amy Hester Student Protection Act, it “requires school districts to report substantiated allegations of sexual misconduct by educators to another school district that seeks a reference for that educator,” according to Courthouse News Service.

On the federal level, no laws regulate the employment of sex offenders in schools, the GAO noted.

But Rep. Michael Fitzpatrick (R) of Pennsylvania is trying to change that. In December he introduced the Jeremy Bell Act of 2011 (HR 3766). The bill would bring fines or prison time to a school employer who facilitates a former employee getting a job in another state if he or she has engaged in sexual misconduct with someone under age 18.

The bill would also tie federal funding to requirements that states have laws mandating reporting by school employees of suspected abuse, and give other educators in the state access to such reports. And it would require schools to check employee fingerprints against national databases.

In the late 1990s, Jeremy Bell was sexually assaulted by his school principal and at one point was given a chemical to render him defenseless, which turned out to be lethal. Parents and teachers had reported the principal to the school board, and he had moved across state lines multiple times for jobs.

Under California rules, Berndt will qualify for pension benefits even if he is convicted, Superintendent Deasy noted in his Feb. 1 letter. The California State Teachers’ Retirement System did not respond to the Monitor’s request for comment.