From overlooked to must-see. LA community’s big statement with Black-centered art.

Loading...

| Los Angeles

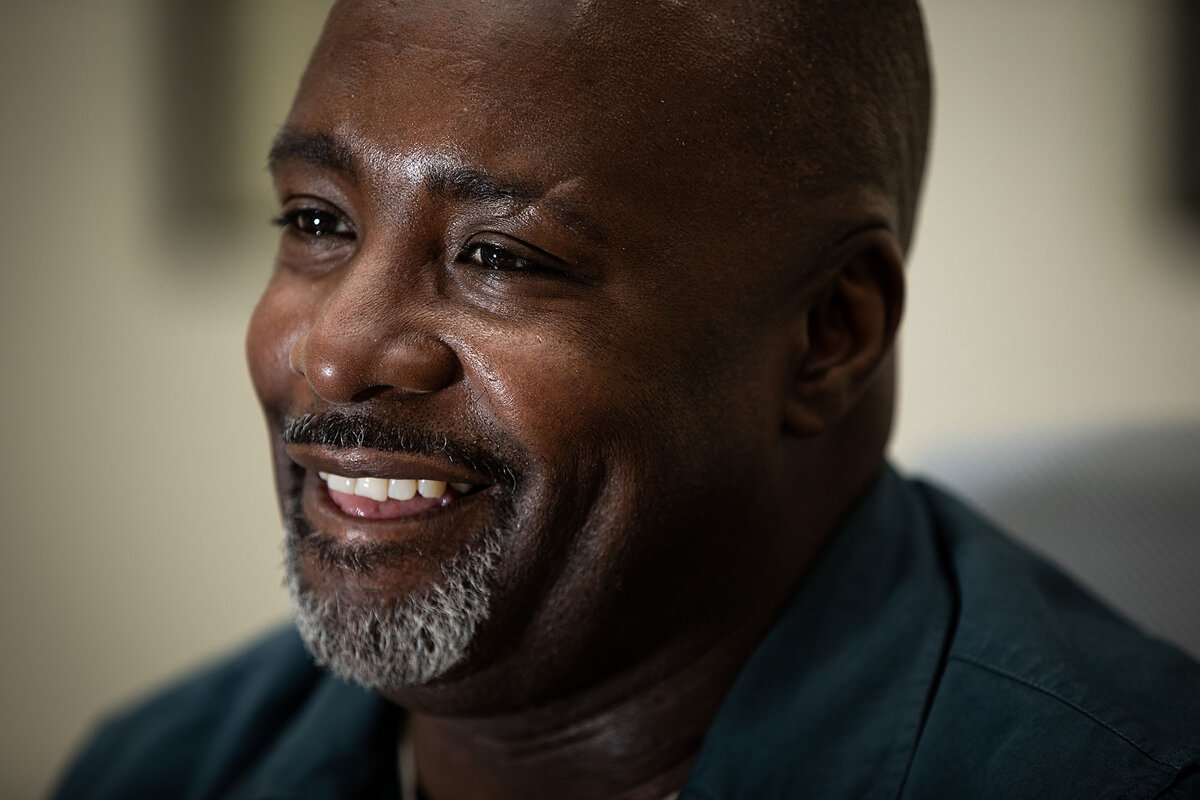

Growing up in South Los Angeles, Anthony Fagan was “very much part of all of the problems that take place in this community,” he says. Today, he’s overseeing construction on a park that is at the heart of efforts to make the Crenshaw District a must-visit stretch of LA.

“We’re going to change lives with this park on so many different levels,” says Mr. Fagan, an assistant superintendent with PCL Construction.

The $100 million initiative has drawn public and private funding to transform a 1.3-mile stretch of Crenshaw Boulevard into the largest Black-centered public art display in the United States. Destination Crenshaw is a holistic plan that weaves economic and community development together with cultural celebration to recast this neighborhood as a tourism center and create economic stability for those who live here – and for generations to come.

Why We Wrote This

An “unapologetically Black” public art project may offer a model for economic justice. At Destination Crenshaw, a storied Los Angeles corridor leverages local culture and hopes to reignite recognition, respect, and revenue.

“This is owning it,” says Jason Foster, president and COO of Destination Crenshaw. “It’s a way for our community to actually embrace folks coming and celebrating what this community is, but also for other communities to acknowledge that this community exists.”

Skeptics and hope

Destination Cresnhaw runs north-south through the Hyde Park neighborhood – part of South LA, known as South-Central Los Angeles until 2003, when the LA City Council changed the name, hoping to dissociate the 16-square-mile area from a reputation for gang violence and race riots.

Destination Crenshaw touches three census tracts that fall in California’s highest quartile for poverty and unemployment. On average, about three-fourths of the residents who live in these neighborhoods are Black.

In the 1950s, South LA had the highest concentration of Japanese Americans in the country, after the U.S. Supreme Court lifted racist housing covenants and Japanese migrant farm workers settled into enclaves like Boyle Heights. Thousands of Japanese farm and railroad workers had arrived in the years leading up to that, too, beginning in the late 1800s, and a surge of migrants moved down after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

African American families soon followed, and by the late 1960s, Crenshaw Boulevard was a corridor of flourishing Black-owned businesses. Leimert Park, capping the northern end of the district, was a center of artistic expression.

Rosemary Williams moved here from Chicago in 1968. She opened Dog Lovers Pet Grooming on Crenshaw Boulevard in 1980 and has since seen other businesses, and neighbors, come and go. The building next door is vacant – it used to be a Dollar Tree, but it fell victim to the pandemic and then to looting, she says, as did other businesses along the corridor. Like many locals, she’s skeptical of the latest initiative. But she also wants it to work – and believes it’s worth a try.

“We’ll see,” she says, adding that she’d like to see the area improve from where it was 10 years ago. “Things were kind of going south for a minute. ... A lot of people lost their properties during the pandemic. So a lot of us didn’t make it. ... That kind of hurts my feelings when I see that happening to other businesses.”

Ms. Williams’ daughter convinced her to participate in Destination Crenshaw’s mural program, which pairs artists with storefronts. Her reluctance gave way, she said, because of the organizers’ efforts to support small businesses and to clean up the area. Standing by a wall of collars and leashes, she details her two demands for the artist: that the mural represent friends and businesses who have persisted here through the decades – and that it include dogs.

Anthony “Toons One” Martin answered the call. He grew up in South LA in the ’70s, and remembers it as vibrant. He turned a talent for graffiti art into a career and worked around the world as a muralist. Today he’s living back in South LA, contributing to the neighborhood that shaped him, as one of the 100-plus artists who will be commissioned by Destination Crenshaw.

His design is titled “Hey Young World,” inspired by the hip-hop song with the same name. He hopes, in turn, to inspire the youth who live here to take pride in their neighborhood and themselves – and dream big about their futures.

“People forget that government is for the people, by the people,” he says. “If we want to see ... solutions, we have to be a part of that process.”

All eyes on Crenshaw

Nobody knows that better than Marqueece Harris-Dawson, City Council member representing the 8th District and a driving force behind Destination Crenshaw. The South LA native came into office as plans were underway to build a light rail station at Leimert Park.

Residents were upset that the line would be built at street level, instead of below or above ground, bisecting their main throughway and disrupting foot traffic. But Mr. Harris-Dawson took a cue from Beverly Hills, which lobbied to have its light rail at grade to showcase the world-famous shopping district around Rodeo Drive, where palm trees punctuate power lunches and luxury stores.

He enlisted the Crenshaw community for ideas about building on the city’s investment – and combating fears of displacement from a spike in property values that often comes with mass transit hubs. What emerged was a plan to capitalize on the art and culture that radiate from this district, stimulate economic development, and strengthen community ties.

“These things are so tied intrinsically together, the money with the architecture with the benefit of the community,” says Valery Augustin, an architect and assistant professor at the University of Southern California. “You need that investment for communities to stay places that people want to go to. And if people won’t invest in communities, then your built areas can’t possibly thrive.”

South LA has nurtured innumerable Black artists and entertainers, many of whom have shaped America’s cultural landscape. And the local hip-hop scene is legendary. But the area has missed out on the economic rewards of its cultural influence.

People associate Black culture with Harlem, Chicago, or Atlanta, “but they don’t think of LA. And it’s because we just don’t put it forward,” says Mr. Harris-Dawson, who was recently elected LA’s next City Council president. “Culture’s coming out all the time and people are consuming it, but we don’t tie it to home.”

In the next few years, millions of metro riders will see this tie up close. Leimert station is on the rail line leaving Los Angeles International Airport. With the FIFA World Cup coming to Los Angeles in 2026 and the Olympics here in 2028, all eyes will be on Crenshaw Boulevard – portal to the City of Angels.

“Unapologetically Black”

Organizers describe Destination Crenshaw as “unapologetically Black.” Sankofa Park showcases that spirit. The triangle-shaped plot sits across from Leimert Park Station, one of a half dozen pocket parks that will offer space for play, perusal, and the simple comfort of connecting with nature. When finished, it will house sculptures by some of the biggest names in contemporary art including Kehinde Wiley, Maren Hassinger, Artis Lane, and Charles Dickson.

Every detail is intentional: The park name – Sankofa – is for the African bird that represents moving forward while learning from the past. Most of the park’s plants are native to Africa. Pathways are lined with cutouts in the shape of African giant star grass, which migrated with enslaved Africans and took root alongside them. Those shapes are echoed in the park’s shade structures. Employing people with strong ties to this community was a priority.

Charles Dickson’s Car Culture is one of the first sights to greet visitors entering Crenshaw from Leimert Park. The highly polished steel sculpture harkens to weekend parades of lowriders, the car dealerships that were once abundant here, and the nearby Goodyear tire factory that shut down decades ago.

When members of his community see it, Mr. Dickson says he wants them to feel important. “I want them to know that they are part of that past, present, and future. ... And so you build up that pride and that confidence that they’re connected, they’re part of something historical,” he says. “The whole process is about a spiritual connection.”

This creative energy amplifies a narrative that the Crenshaw community has held all along.

“We’re incredibly human,” says Mr. Harris-Dawson. “And we’re incredibly human in that we hold close to our hearts the struggle to be in our humanity and to be protected in our humanity and affirmed in our humanity.”