Lights on, but trust off. Texas tries to rebuild confidence in grid.

Loading...

Listen to the full story, and hear about the reporting

Before February 2021, few Texans knew the minute details of how electricity flowed through the state. Then, just before Valentine’s Day that year, the flow stopped.

A massive winter storm swept through Texas, triggering blackouts in millions of homes across the state. Some Texans spent days in the dark and cold. Many also lost running water, and hundreds lost their lives. By Feb. 18, 2021, everyone in Texas knew the name of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas. And they knew they couldn’t trust it.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe Texas power grid is more reliable today than it was three years ago, when a massive winter power failure convulsed the state. But officials are finding that restoring trust is a demanding and long-term process.

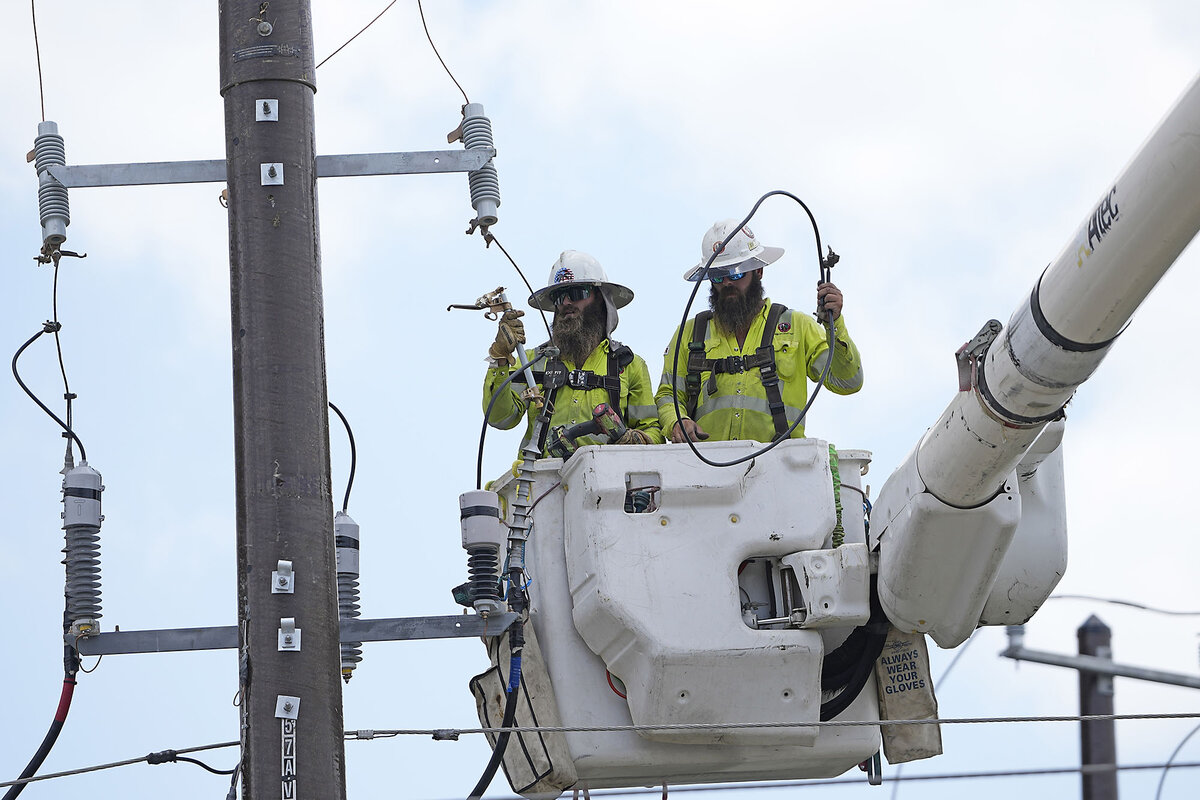

ERCOT doesn’t bill anyone or provide any electricity directly to consumers. It simply manages the flow of electricity through the Texas power grid. Since the blackout, the grid – which ERCOT oversees – has undergone significant changes. The Lone Star State has also experienced more extreme weather, including another major winter storm and two intense summer heat waves, without the kind of widespread system failure seen during the 2021 storm.

Indeed, the Texas power grid is more reliable today than it was three years ago, the result of significant changes in oversight, storm readiness, and capacity, experts say.

But what hasn’t changed much? The trust Texans have in it. In a survey released last month, a Texas electricity provider found that nearly 7 in 10 Texans “have low trust in ERCOT and the stability of the Texas power grid.”

Because while state regulators and officials have made some improvements, they’ve also made some mistakes, experts say. The grid is, in fact, more reliable, but power bills are higher for many Texans. ERCOT has also often asked residents to conserve electricity during severe weather events, eroding confidence that the grid has become more resilient.

There’s also an emotional layer that state officials need to work through, say grid watchers. As in any human relationship, Texans felt betrayed when the grid wasn’t there for them, says Joshua Rhodes, a research scientist at the University of Texas at Austin.

“It’s deep in the Texan psyche now to worry about the grid,” he adds.

“The grid is more reliable,” he continues. But to rebuild trust, “it’s going to take a lot of time and hard work, and being consistent about keeping the lights on [and] making people feel safe.”

The Lone Star State’s lone road with power

In a few ways, the Texas power grid is unique.

ERCOT is the only grid network in the United States that is not connected with other grid systems. This has meant the Texas grid isn’t covered by federal regulations. It also means that Texas can’t draw power from other states when needed.

Normally this isn’t an issue. Through natural gas and, increasingly, renewable energy sources, Texas produces more electricity than any state in the country. ERCOT, meanwhile, manages the flow of all this electricity. When demand looks like it could exceed supply, ERCOT can tell more generators to come online. It can then also ask Texans to conserve electricity.

ERCOT isn’t a state body itself, but it’s overseen by one: the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUC). In February 2021, this system collapsed amidst days of subzero temperatures, freezing rain, and record snowfall around the state. Energy sources froze up, and power plants broke down.

All forms of power generation failed, but the bulk of the outages came from the natural gas supply, which provides most of the grid’s electrical capacity.

To prevent an uncontrolled, systemwide blackout, ERCOT cut power to millions of homes across the state for days until generators could come back online. ERCOT and the PUC struggled both to restore power around the state and to communicate what was going as Texans sat freezing in their homes, few of which are winterized. As the snow melted and lights turned back on, demands for reforms soared.

And reforms happened. State lawmakers replaced the entire ERCOT and PUC leadership in the months after the storm; the Legislature passed a law requiring power plants to weatherize. Texas’ plant weatherization standards are now the strictest in the country, according to Will McAdams, who served on the PUC from April 2021 through December 2023.

Meanwhile, ERCOT launched a program to increase its supplies of emergency electricity. The grid network is also adding renewable energy capacity at a prodigious rate. No state produces more wind power than Texas, which could soon also overtake California as the country’s leader in solar power. Battery storage is also poised to increase substantially.

“The capacity we’re adding right now – which is mostly solar and storage – is contributing in a major way to reliability,” says Doug Lewin, an expert on the Texas electrical grid and author of The Texas Energy and Power Newsletter.

“There’s still room for a lot of improvement, but the outages for particular thermal [fossil fuel] power plants are down quite a bit,” he adds. As ERCOT expands supply, especially with renewables, it also needs to expand its grid infrastructure. This work has begun in some ways, such as adding transmission lines in South Texas and integrating more customers onto the grid in the Texas Panhandle. But other improvements have yet to begin.

Keeping lights on

Still, many Texans remain skeptical that the lights will stay on when the weather gets bad.

While regulators and lawmakers have improved the grid, they’ve also misstepped. In the aftermath of the blackout, for example, some Texans received massive electricity bills because the PUC had raised prices during the storm in an effort to increase conservation.

Bills have also stayed high for many consumers as electricity providers have made infrastructure improvements and expanded connections for the state’s growing population. One woman in the city of Nevada, Texas, was billed $6,200 the week after the storm, more than she paid for electricity in all of 2020, The New York Times reported.

Some policies have also been criticized. Amidst record-breaking heat last summer, ERCOT paid bitcoin mining companies – huge warehouses of servers that run code that creates bitcoin – millions of dollars to reduce their energy usage. The grid operator then proposed, but canceled, a plan to revive some old fossil fuel plants last winter. ERCOT also tried to enact a regulation that would limit the use of battery storage – a technology projected to increase capacity by 157% this year.

Dakota Johnson-Martinez, who lives in San Antonio, weathered the 2021 storm reasonably well. She lost power intermittently, but not water, so she spent the week huddled under blankets playing games with her three children.

Still, three years later, she doesn’t trust that the power grid has improved. She only needs to look at her bill to see that the average monthly price of electricity has increased from 11.73 cents per kilowatt-hour each month in 2020 to an average of 16.66 cents per kilowatt-hour for the first six months of 2023, according to BKV Energy, a Fort Worth-based utility company.

“You keep raising our rates. Why aren’t you doing anything with it?” she asks. “I know that we have the windmills; I know we have the solar farms,” she adds. “And every time it gets too hot, they ask us [not] to lower our temperatures.”

And they don’t just ask when it gets hot. Over the past eight months, Texans had their phones blow up 13 times with warnings from ERCOT asking them to conserve electricity.

While there hasn’t been a widespread blackout, to many Texans these alerts are evidence of continuing grid frailty. From ERCOT’s perspective, however, they are intended to have the opposite effect. The grid is more reliable, experts say, and the grid operator is communicating with the public better than it did during the 2021 storm. But ERCOT may have overcorrected.

“People are getting annoyed with that,” says Mr. McAdams. “But it’s designed to increase public trust, so the public knows what’s happening and why it’s happening.

“I think it’s exacerbated some lack of trust that was already there,” he adds. “But over time, and if we don’t have emergency conditions, if we’re able to prevent that type of experience with the public, I think that can be restored. It will come slowly, and incrementally, but it will come back.”