If Uvalde inspires gun control, ‘red flag’ laws are most likely

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga; and Washington

An hour after he visited an elementary school to vote in a runoff election on Tuesday, state Sen. Nathan Johnson started getting texts about another Texas elementary school. Five hours away from his district office in Dallas, there’d been a shooting in Uvalde.

Thinking about the school he visited – crepe paper art projects on display, kids at play in little voices – Sen. Johnson said he was overcome by the “contrast.” Peace in Dallas. Horror in Uvalde.

In an emotional phone interview with the Monitor, the Democratic senator said that as the news came, his mind went to Robb Elementary School and two colossal what-ifs: Two “red flag” laws he’d supported in the Texas legislature last year and in 2019.

Why We Wrote This

“Red flag” laws which allow temporary removal of firearms from someone deemed legally dangerous are a rare area of agreement on a solution for gun violence. Emerging evidence suggests they do reduce violence when used.

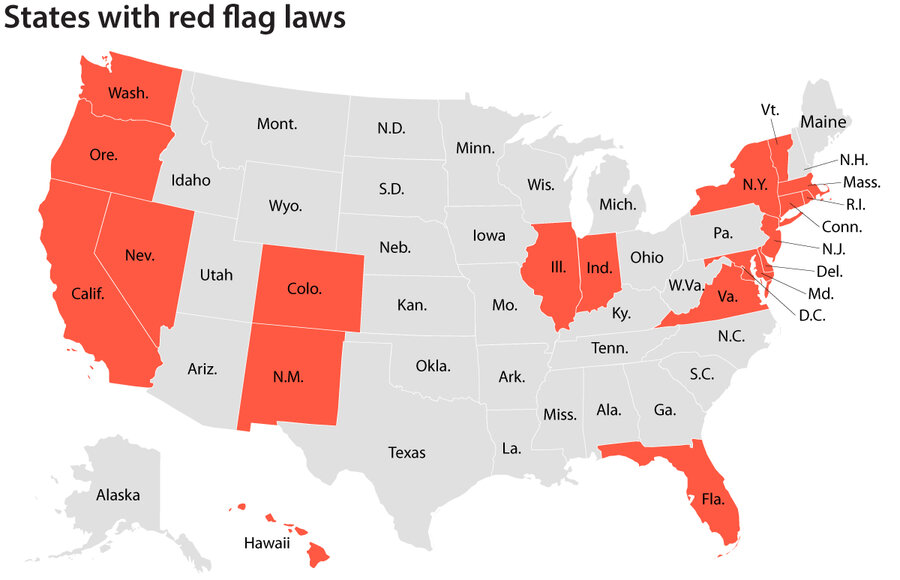

Also known as extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs), these were gun control measures similar to those that exist in 19 states (plus the District of Columbia) and allow police to temporarily remove firearms from someone a judge deems highly dangerous. Both of Sen. Johnson’s bills failed.

“It really hit me,” he says. “It hit me as a legislator. It hit me as a dad. It hit me as somebody who just voted in elementary school. It hit me as a senator who had just visited a local elementary school a month before and got cards from kindergartners. We can’t even have a red flag law?”

In the three days since 19 students and two teachers lost their lives in Uvalde, many Americans have felt a similar sense of futility. One in 5 reported in a Yahoo News/YouGov poll this week that there is nothing the country can do to stop more mass shootings.

But pleas for reform continue, and red flag laws may be one compromise solution. Uncommon before 2014, such laws have now been passed in 19 states and the District of Columbia – including gun-friendly Indiana and Florida. Half of all Americans now live in states with a red flag law, and the legislation is overwhelmingly popular in polls.

That doesn’t mean more will pass. Still, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has hinted in the past he might support one, as have some Republican senators in Congress, like Susan Collins of Maine and Lindsey Graham of South Carolina.

If any public safety legislation emerges from this week’s shooting, it’ll likely be an ERPO.

We “don’t have to wait until the trigger is pulled to intervene,” says Joseph Blocher, a professor of gun rights and regulation at Duke Law.

Red-flagging behavior, not identity

The argument for an ERPO is that not all people who are armed and dangerous have a criminal record that would prevent them from purchasing a weapon – nor will they even come in contact with police, says Richard Bonnie, director of the Institute of Law, Psychiatry, and Public Policy at the University of Virginia.

Red flag laws are like a protective order for guns. Family members, police, or other close contacts can argue in court that someone they know may harm themselves or others, and that law enforcement should remove that person’s weapons. If the judge issues an order, police may take the firearms for a short period – usually less than two weeks. Then, at a hearing, the person who lost their firearms can argue to get them back. The burden of proof, says Professor Bonnie, is usually on the court to keep them, not the citizen to get them back.

Part of what makes these laws so popular is their specificity, says Professor Blocher. “This is what I call retail-level gun control,” he says. “It’s focusing on the individual rather than the group.”

Even more, says Professor Bonnie, on an individual level the laws focus on behavior, not identity. They maintain everyone’s right to bear arms, he says, while acknowledging that people can be temporarily unstable. That, itself, is something of a check on gun control. “You want to actually be able to prove your basis for the worries ... to protect the rights of the person from an unwarranted intervention,” says Professor Bonnie.

Because the laws are designed to prevent gun violence, it’s hard to measure their exact effectiveness.

But Connecticut has seen a 14% reduction in its firearm suicide rate after increasing enforcement of the law, and another study estimated that for every 10 to 20 guns detained there, one life is saved. California has seen dozens of seizures from people who made terroristic threats – none of whom carried out any attack after the civil order was issued against them. Florida, which enacted its ERPO after the mass shooting at a high school in Parkland in 2018, is one of only two Republican states with a red flag law. But it’s also one of the most active, averaging multiple uses a day in some years.

“Whether something would have happened or wouldn’t have happened, obviously, is an unanswerable question,” says Professor Bonnie. “But I think what you can demonstrate is that you definitely reduce the risk in these cases.”

Promising results

To be sure, red flag laws are no panacea for mass violence.

Such laws are more effective in preventing suicides – the majority of gun deaths each year – and not mass shootings. Most often, one study in Connecticut found, they help address personal problems among older married men, sometimes veterans. Mass shooters are often much younger, and haven’t had much time to establish a criminal record.

Even in states that have them, ERPOs aren’t always invoked when needed. New York has such a law, but it didn’t stop the shooting in Buffalo earlier this May. Red flag laws require someone to act on red flags.

And the deadly impact of gun violence on society and its most vulnerable keeps mounting. 2020 marked the first year ever when more American children died by gunfire than in car accidents. For a confluence of factors, mass shooting events are up 50% since FY 2018-19, the FBI reported this week.

“These are promising [laws], but they are very new,” says Lisa Geller, state affairs advisor at the Center for Gun Violence Solutions, at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore.

As with any new law, misconceptions abound. Professor Blocher, of Duke, says many people fear permanent confiscation of their guns or criminal penalties if they act on the laws. Neither of those strictures are part of red flag laws.

For some, like Mark Pennak, the problem isn’t misconceptions; it’s disagreement. The president of the gun-rights group Maryland Shall Issue, Mr. Pennak says ERPOs threaten Fourth and Second Amendment rights of due process and to bear arms.

“They’re going to go in and take his equipment, something he has a constitutional right to possess, because they think he might commit a crime in the future,” he says. “This has huge due process problems.”

Having an armed government employee confiscate a law-abiding citizen’s firearms is, in some ways, a gun advocate’s nightmare. But even Mr. Pennak concedes there are circumstances that should disqualify someone from gun ownership. He mentions existing laws in Maryland and elsewhere that permit a court to take weapons after an interview with a mental health professional.

“There is a whole existing separate ... procedure for doing that and we never have opposed that,” says Mr. Pennak.

It doesn’t always work

Existing procedures didn’t work this week in Uvalde. Hence, on Tuesday, Sen. Johnson found himself frozen in moments of legislative failure.

“I’m never one to claim that passing a single law, gun safety law or otherwise, is necessarily going to avert the next tragedy,” he says. “But the failure to try struck me as just sickeningly ironic.”

He says he’ll be talking to his Republican colleagues before the legislative session begins this year, looking for a compromise. Sometimes, he struggles to remain optimistic.

In conversations with gun-owning friends, he still finds himself convinced that some gun safety laws are better for their right to bear arms. Texas passed Constitutional Carry last year, allowing residents to carry a gun in public without a permit or background check. “Could that reassure Texans that their rights aren’t in danger?” he wonders aloud on the phone.

“The more tragedy and damage that’s inflicted by guns, the less stable is their right to keep one, because eventually people are going to get sick of this,” says Mr. Johnson.

“Or are they? I don’t know.”