Police reform: Why it’s so tough to get – and keep – the right chief

Loading...

In his 32-year career in the Miami Police Department, Capt. Delrish Moss served under 11 different police chiefs. He learned something from each one, but when he left to become chief of police in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2016, one piece of advice stood out.

Being a police chief means working on a three-legged table. Politicians are one leg, the community another, and the rank-and-file another.

“You have to make sure all the legs are sturdy and balanced,” says Captain Moss, who now works in the police department at Florida International University in Miami.

Why We Wrote This

Police reform can sometimes depend on getting the right police chief. But cities might be churning through them too quickly to create real change.

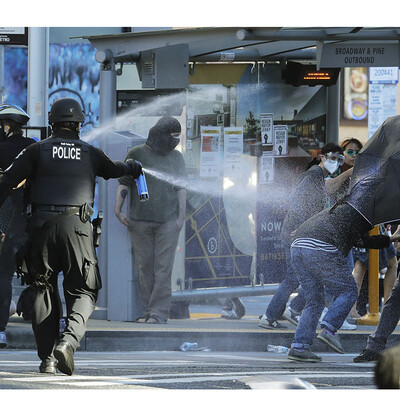

In Ferguson, he took charge of perhaps the most precarious three-legged table in the country. He was the city’s first permanent chief since the police shooting of Michael Brown triggered a federal investigation and consent decree, as well as nationwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism. The community didn’t trust local police, and it didn’t trust out-of-town police brought in to fix things either – a protest greeted Captain Moss on his first day.

He left Ferguson 2 1/2 years ago to care for his ill mother. He’d accomplished some of his goals by then, he says, such as increasing the number of Black and female officers in the department. But many needed more time.

“It takes about five years to create a cultural shift,” he says. Changing a chief in the middle of that, when they’ll “want to put their stamp on things,” he adds, “can be confusing.”

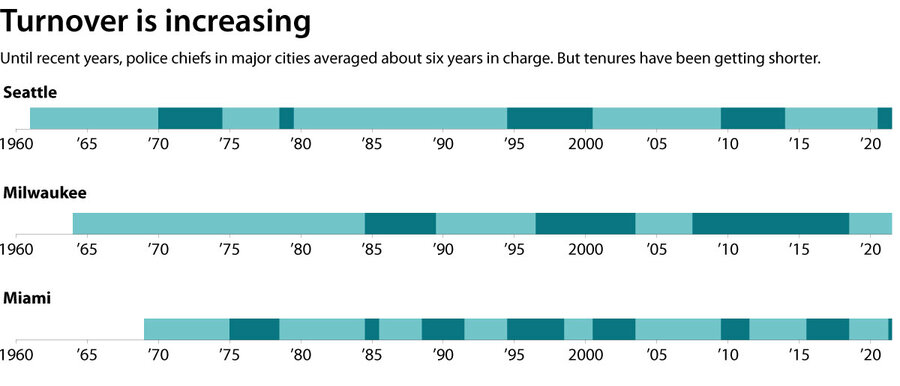

Changing a police chief can be a powerful lever for reform. But changing them too often can be a hindrance. Historically, chiefs averaged five to seven years at a department, according to Laura Cooper, executive director of the Major Cities Chiefs Association. Today, the average tenure is around two to three years. And in the past 18 months or so, top cops around the country have been turning over with unusual frequency.

That intensified churn is a product of efforts to reimagine policing in the wake of the murder of George Floyd last year. Amid intense scrutiny from the public – and spikes in violent crime – 40 major cities have changed police chiefs since January 2020, says Ms. Cooper. The question: How much churn is too much?

“To institute culture change and really see reforms come to fruition, it takes a little bit of time,” she says. “With turnover every two or three years, you’re not going to see it.”

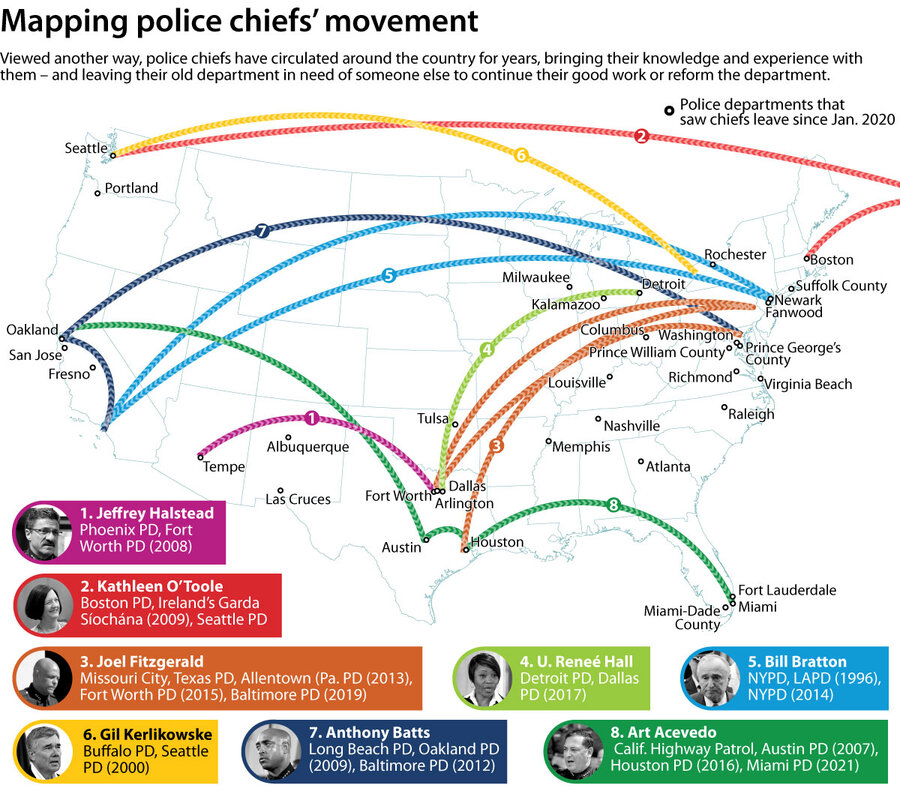

Cities often turn to new police chiefs much like struggling sports teams turn to new head coaches or general managers, hoping to reverse their fortunes. Many police chiefs, in turn, have spread their philosophies as they’ve moved from city to city.

Bill Bratton, for example, controversially pioneered the use of aggressive, data-driven policing to reduce crime over a three-decade career running police departments in Boston, Los Angeles, and New York (twice). Charles Ramsey moved from Chicago to Washington to Philadelphia, developing a model that emphasized community policing and improving recruiting and hiring standards.

In the past 18 months, however, police chiefs have increasingly been leaving not only departments, but also the profession entirely. That’s partly due to a generation of chiefs reaching retirement age. But some younger, reform-minded police chiefs are being forced out, too.

For “old school” chiefs who are “uncomfortable” with increased oversight and questioning about policing, “they’re making a wise decision by leaving the profession,” says Alex del Carmen, a criminologist at Tarleton State University in Fort Worth, Texas.

But there’s also “an incredible amount of institutional memory leaving the ranks of law enforcement,” he adds. “That concerns me.”

Ms. Cooper says that policing is experiencing a drain of “thought leaders.” For example, former Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best resigned last August after the city council voted to downsize the department. She said the move would disproportionately harm officers of color she’d recently hired.

“That’s an instance where you have a good chief, a forward-thinking chief, who’s dedicated to reform and wants to do the right thing,” says Ms. Cooper, “and she was pushed out.”

Periods of high turnover have happened before.

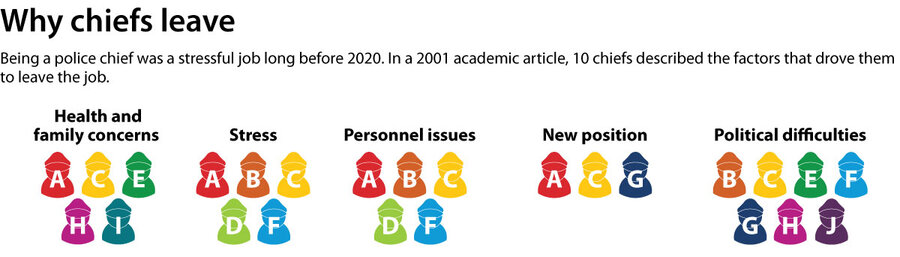

In 2001, Mary Dodge – a professor of criminology at the University of Colorado – co-wrote a paper examining what she described as “alarmingly high rates of police chief turnover.” Chiefs’ balancing acts are never easy. “They’re trying to please the public, the rank-and-file, and the politicians. You can’t possibly make every constituent happy,” says Professor Dodge.

Cities, departments, and chiefs need to better ensure that a change in top cop isn’t “a traumatic event to an organizational culture,” says Professor del Carmen. When a reform-minded chief leaves, the reform process doesn’t have to leave with them.

In Ferguson, Captain Moss lobbied publicly for one of his assistant chiefs, Frank McCall, to succeed him.

“Frank and I had fashioned that vision [for the department] together,” he says. “Had [he] stepped in I think it would have been a smooth transition. … That would have kept fluidity, consistency and momentum.”

Ferguson officials chose someone else, but earlier this year that chief announced that he was leaving to take over a police department in North Carolina. Assistant Chief McCall, who had stayed on after Captain Moss left, became Ferguson’s police chief last week.

Ferguson is now on its sixth police chief in six years. That may be too much turnover for one city, but Captain Moss doesn’t think having churn at the highest ranks of policing in the country is a definitively good or bad thing.

“Every department, every city has to assess what direction they want to go in,” he says. “It really depends on the dynamics on the ground, and who you bring in.”

One thing cities should do, he adds, is heed the lesson of another chief of his in Miami: Everybody knows that police officers don’t study history.

“We need to be better at learning from [the past] and better at examining those things,” he says, “in our profession but [also] on a larger scale.”

That three-legged table, he adds, nationwide, “is in a super precarious position right now.”