'Above normal' hurricane season coming. Is New York ready for another Sandy?

Loading...

| New York

Weather forecasters are saying the East Coast could be in for another wind-whipping storm season, but is New York City prepared?

It’s been less than 10 months since hurricane Sandy sent surges of flooding saltwater into city streets and tunnels, devastating coastal residences and shutting down much of Manhattan’s southern tip.

But while the city continues to work tirelessly to clean up Sandy’s ravages – helping more than 20,000 residents rebuild, distributing more than 3 million meals, and clearing nearly 700,000 tons of debris – it is still sifting through a dizzying host of recommendations, both large and small, as it tries to make the nation’s largest metropolis more resilient to future storms.

Yet most of these efforts remain in planning stages – or rather, as discussion topics. To date, city agencies have been able to do little more than shore up existing emergency procedures.

"The City has done an enormous amount of planning, and there are a number of concrete steps that have been taken, including the new evacuation zones and the reconstitution of our stockpile for our shelters," says Christopher Miller, spokesman for New York's Office of Emergency Management. "But some of the larger mitigation efforts will take more time."

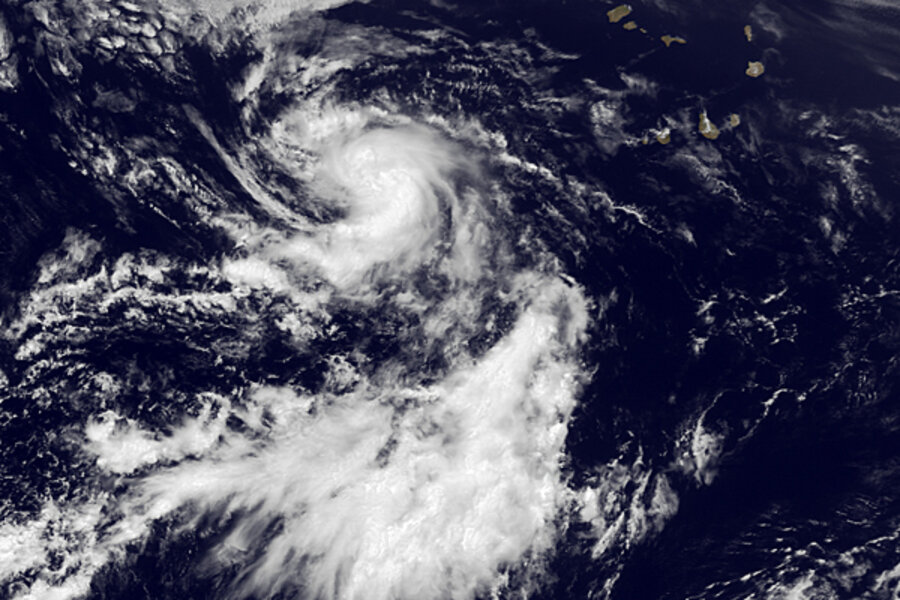

Though experts say the likelihood of another Sandy-like storm hitting New York is minuscule, on Thursday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said there was a 70 percent chance this year’s Atlantic hurricane season would be “above normal,” predicting about six to nine hurricane-grade storms with sustained winds topping 74 mph. More ominously, the agency also said three to five of these storms could develop into major hurricanes, with winds of 111 mph or higher churning up the Atlantic Ocean and potentially threatening US coastal communities.

“I think if we had another Sandy this summer, I think there’s no question that the city would be better prepared,” says David Reiss, a professor at Brooklyn Law School who teaches the impact of climate change on cities. “But I don't think they've made massive changes to how we do things – they have just dealt with it once, and know what the challenges are, and can be better able to implement and execute [emergency procedures.]”

In May, the city released its “After-Action” report, an extensive review of how well city agencies were able to implement such procedures, offering suggestions for improvements. Among these were improving the city’s 311 and 911 services, expediting the purchase of public safety equipment, and developing more comprehensive power backups for street lights and city residences. But most of these recommendations are simply that: recommendations.

In June, Mayor Michael Bloomberg outlined a massive and far-reaching series of steps the city could take to protect itself from the threat of rising sea levels – as well as the kind of storm surge seen last October. The 438-page report had over 250 recommendations, including systems of levees and flood walls and long-range improvements to the city’s infrastructure – a $20 billion plan Mayor Bloomberg himself called “incredibly ambitious.”

“You have to realize that we're only 9 to 10 months since this all happened, and the universe of New York City can’t change that quickly,” says Dan Wurtzel, president of property management at FirstService Residential New York, which oversees about 600 residential apartment buildings in the city. Nearly 50 were damaged and 75 more lost power in last October’s storm.

But the city has been doing smaller, less-ambitious preparations, such as shoring up its beaches with higher sand dunes, revamping its evacuation zones for more efficient first responses, and restocking emergency supplies for city-wide emergency shelters.

And as the city rebuilds, officials are writing new codes for more hurricane-resistant buildings – especially for older structures. Mr. Wurtzel explains, “If your building is located in a flood zone, you may have to relocate your equipment above the ground floor, or you’ll have to put it in a watertight room. These are things that will probably come into effect, if they haven’t already done so.”

Yet experts continue to say that informing people how to prepare themselves remains a key part of hurricane preparation.

“Last year people had no idea in the Northeast that there is such a thing as a hurricane season,” says Alan Rubin, a New York-based government relations specialist with Cozen O'Connor law firm. “So at least now there’s information about it.... I think [the Bloomberg administration] has done a very good job in letting people know the hurricane season is here, what they should do, and people are paying attention to it.” [Editor's note: The original version of this story said Cozen O'Connor is based in New York. It is based in Philadelphia with offices in New York.]

But Mr. Rubin, also a former vice president with the Miami-Dade Economic Development Agency, where he led major reconstruction efforts after Hurricane Andrew in 1992, believes that in addition to stockpiling electrical generators, water, and ready-to-eat food supplies, the city should also have a more decentralized structure to deal with the fog of emergency situations.

“We should have command centers in the boroughs that are independent of a central command center, because sometimes those communications are damaged," he says. “You should also be dealing with the utility companies, to make sure that they have set up a separate command center for first responders.”

In the end, however, New York may be at the mercy of Mother Nature this summer. “They took real steps before Sandy last year,” says Wurtzel. “Then the storm hit and it was a mess afterwards."

“The fact remains, if you live near water, and you get a bad storm, you’re going to feel those effects,” he continues. “There’s not much you can do to prevent the water from coming up, and we have to recognize the fact that we may be prone to a very strong hurricane that inflicts damage.”