My electrifying experiment in elocution

Loading...

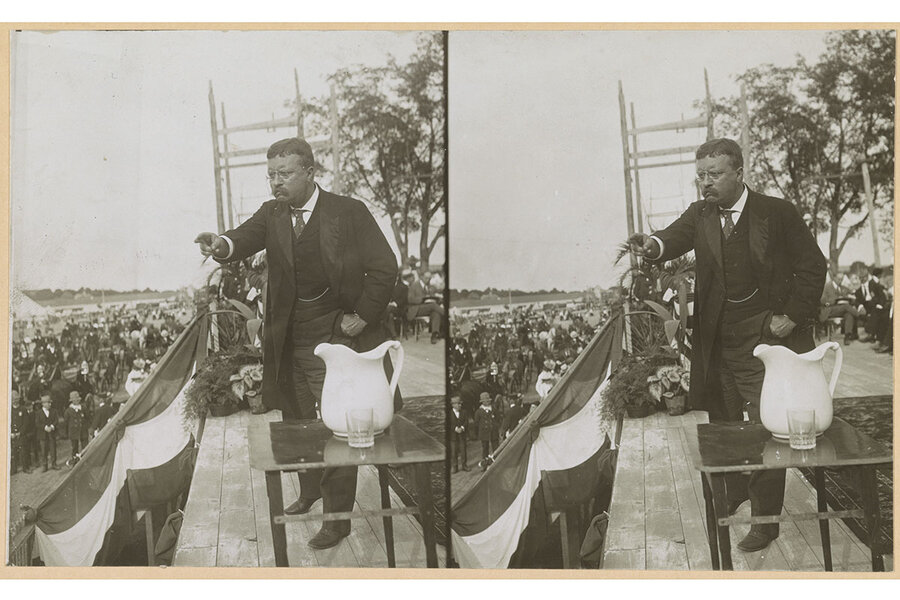

I was noodling on YouTube recently and came across a clip of Theodore Roosevelt giving a speech to a clearly rapt audience. Teddy did not read his speech, nor did he refer to any notes, but his delivery was still lucid, dynamic, and clearly enunciated. To quote him: “Our task as Americans is to strive for social and industrial justice, achieved through the genuine rule of the people.”

The next day, when I got to the university class I teach, I was still glowing. I asked my students if any of them knew what “elocution” was. One responded, “Like, when you touch a live wire?”

Bless her heart. She’s blameless, of course. Elocution in American public schools went out with high button shoes.

For the uninitiated, elocution is the art of formal speaking, with due attention paid to pronunciation, grammar, style, and tone. It had its heyday in the 19th century and was still extant in the early part of the 20th. Soon thereafter, such instruction rapidly declined.

There was still an echo of it when I was in elementary school in the 1960s. In sixth grade each of us had to commit a poem to memory, and then recite it before the class using appropriate dramatic gestures and clear enunciation. I was terrified. But I got up the courage to recite Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Village Blacksmith” and was relieved when the ordeal had passed.

It wasn’t until years later that I appreciated what my teacher had been trying to do: get us to be mindful of the clean, clear, and confident delivery of language, thereby investing it with power.

So, is elocution really a thing of the past? When one listens to the halting utterances of contemporary politicians or pop culture celebrities, one might be tempted to think so. But although elocution is no longer being taught, it does erupt from time to time as a natural talent, in the same way that someone may have a head for math or an ear for music. I think of the soaring rhetoric of Martin Luther King Jr. (“I have a dream”), the civic boosterism of John F. Kennedy (“Ask not what your country can do for you”), and the hopefulness of Barack Obama (“We can acknowledge that oppression will always be with us, and still strive for justice”).

Would elocution stand a chance if it were formally reintroduced into the school curriculum today? It’s an intriguing question. Elocution was born when there were no means – other than the written word – of communicating across distance. No radios, phones, TVs, or computers. To have an educated man or woman come to one’s town to give a formal speech about things that mattered was a real event – it showed what language was capable of in the hands of a master of rhetoric. Ralph Waldo Emerson could pack a huge hall, speaking on subjects as diverse as poetry, politics, and self-reliance. The irony is that today we are all about communication, awash in a sea of language, but despite its abundance, very little attention seems to be paid to its refined usage.

In this light, I decided on an experiment. I took some time to commit Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address to memory. And then, alone in my room one evening, I recited it aloud as if I were presenting it to an attentive audience. And then I repeated it. And then a third time. With each repetition I understood it better, grew in confidence, and felt myself being transported by its wisdom. By the third iteration its power, import, and beauty sank in, like a shock of recognition.

It was, in the words of my student, like touching a live wire.