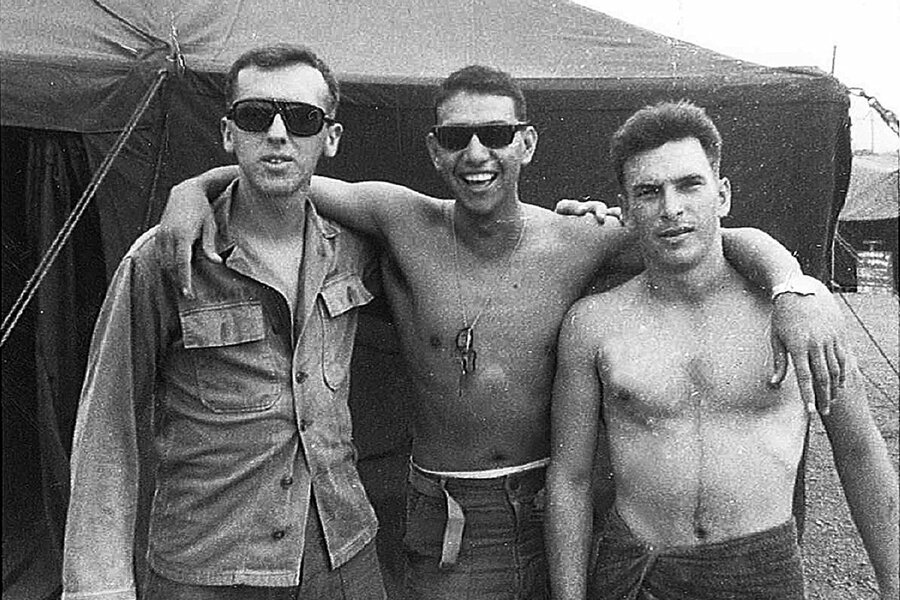

Chu Lai, Vietnam, 1966: My life lesson in leaping

Loading...

Until recently, I’d almost completely forgotten about jumping off the cliffs into the South China Sea when I was 18 – nearly six decades ago. Maybe it was the pandemic that pulled the memory back, or maybe it was my wife mentioning French philosopher Albert Camus and his notion of jumping off a cliff. (“Or should I step back from the edge, and let the others deal with this thing called courage,” he mused.)

I had volunteered for service in Vietnam after being posted at a Marine Corps air station in North Carolina. When we landed on the metal strips of the runway in the port of Chu Lai, I felt the heat reflecting off the metal even before we got off the plane. It was one of the hottest summers I’ve ever experienced.

***

My orders were for Force Logistics Support Group Bravo, where I helped unload boxes of cargo coming off the ships at the base for a month or two before I was ordered to report to another outfit.

The sergeant in charge of our makeshift platoon in Chu Lai was a Korean War vet. I think he knew where we new guys would be going once our work was done there.

So, in the late afternoons when our 10-hour shift was over, he’d take six or seven of us to the high cliffs above Division Headquarters in Chu Lai, and there he told us we were going for a swim in the South China Sea. But in order to do so, we had to leap off the cliffs into the water below – a 35- or 40-foot drop. There were rocks below, jutting out from the froth and waves, but if you ran and jumped, you could make a clear landing in calmer water.

Or course, our sergeant went first. Then, laughing and waving from the ocean below, he urged us on.

One by one, we joined him. It was a crazy, wild kind of thing to do – and to keep doing. It took a good 15 minutes to climb back up the cliff and do it again, which is just what we did.

Looking back now, I realize that the Sarge already knew then that we would all be leaving soon; he was also the guy who refused to let me volunteer for a line outfit, a combat group. One night, a call came out for men, and Sarge cut me out of orders for an infantry company that was taking 50% casualties in late July. He knew that we all would face severe challenges when our orders finally came through. There was no sense getting ahead of things, of rushing toward the inevitable. For him, I think, the cliff jump was a metaphor for what lay ahead. But only now do I discern his purpose in taking us to the cliffs. Back then, I had no clue.

***

Six decades later, when the pandemic hit, I remembered that sergeant – Sergeant Bethlehem – again. I recalled his lesson of leaping into the unknown. It was his way of facing adversity, his notion of staring down into the crashing waves of the ocean and leaping off those cliffs. And although I lost contact with him after I was transferred and he returned home when his tour of duty was finished, I never forgot him or his challenge to us – his need to make us face adversity and the unknown future without flinching. I wish I could thank him, even though he’d probably shrug it off with a wry smile or a laugh. I’d thank him for enabling me to face my own future with a confidence I hadn’t had before, a confidence that has stayed with me all these years.