How I stumbled upon a work of art in Greenland

Loading...

I have only one small piece of original art in my home, but I do have my fair share of kitsch – a ceramic frog sponge-holder, a slate shingle with a hand-painted largemouth bass, a statuette of an Icelandic troll, and a crudely hand-carved wall hanging of a moose titled “Maine.”

I don’t consider this a failing. I long ago made peace with having a poor eye for art, especially art of the modern ilk. But in the company of friends who consider themselves art mavens, I have learned to nod sagely when looking at a pile of broken dishes titled “Flight” and utter, “Very interesting.”

Be that as it may, not long ago, I unexpectedly came into an art piece that has become my pride and joy.

It was like this:

Two summers back I took a trip to Greenland. Because it was different. Because I knew it wouldn’t be crowded. And because I wanted to visit the Viking ruins, which have fascinated me since childhood.

I caught a flight out of Iceland and landed on Greenland’s southern tip to mercifully balmy weather. Then I traveled by boat up a breathtaking fjord, along which the Vikings had settled. Greenland is otherworldly, so much so that, seeing it for the first time – with its muscular mountains, drifting icebergs, and endless expanses of boreal nothingness – it was difficult for me to grasp that such a place really exists.

My first stop was a settlement called Igaliku. It was the Greenlandic trifecta of my dreams: different, uncrowded (pop. 55), and sporting Viking ruins. What more could I ask for?

I found a bed in a small hostel at the edge of the fjord. Other guests included some native Greenlanders: two grandmotherly Inuit women and three children. The children, two boys and a girl, were all around 5 years old. That evening, at dinner time, I went into the common kitchen and found them eating together. I introduced myself and found that one of the women spoke some English.

I felt comfortable asking them questions: Where were they from? Were these their grandchildren? How do you say “Thank you” in their language? Qujanaq (GOY-ee-nak). They seemed happy to oblige me. It turned out that the women were social workers from a settlement on the other side of the fjord and the children were three of their charges. I asked if I could take a few pictures for my travelogue. The smiling response – “Aap” (Yes).

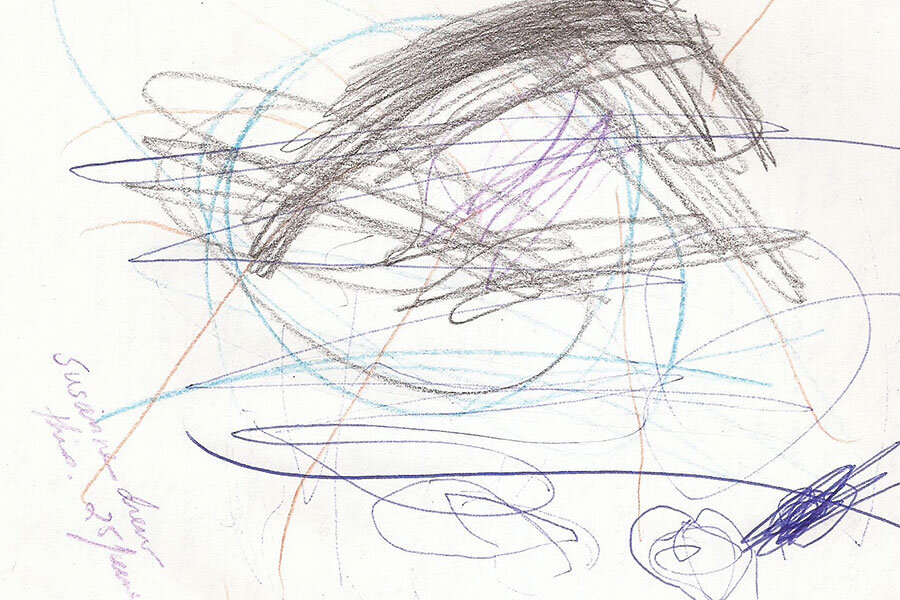

The thing is, the children saw this as an opportunity for play and began to climb all over me and reach for my camera, which I tried to hold out of reach, to little avail. Little Susanne – a brown-haired, brown-eyed girl with the loveliest native features – was the most curious, and insistent. I finally arrived at an accommodation with her: I let her examine the camera as she sat in my lap. I took advantage of the lull to open my journal and jot a few notes. Without warning, Susanne produced a set of crayons, grabbed the journal, and began to scribble in it.

One of the women interceded on my behalf. I could tell from her tone that she was scolding the child. When she moved to take Susanne by the arm, however, I gestured for her not to. “Please,” I said. “Let her draw. What you see is a mischievous kid, but what I see is genuine Greenlandic art.”

And so we all hung fire for the next five minutes or so, while Susanne indulged her creativity. “Qujanaq,” I said once she was done, and she beamed.

That’s how I came into my one piece of original artwork, which hangs proudly on the wall. When visitors pause to admire it, I remark, “I find this artist very mischievous, don’t you?”

And my guests wonder at my sagacity.