Ken Burns on why he lassos stereotypes in ‘Country Music’

Loading...

Few categories in American popular music are subject to more contentious debate today than country. The genre finds itself rocked by questions of inclusivity: Is there room for women and minority groups in a category that has become closely identified with white males?

Superstar Sara Evans has said that she feels disconnected from many of the male-oriented songs that receive radio play, including the sometimes chauvinistic songs belonging to the “bro-country” subgenre. And, earlier this year, African American artist Lil Nas X found his genre-sampling hit “Old Town Road” dumped from the country chart of Billboard.

Into this controversy enters acclaimed nonfiction filmmaker Ken Burns, whose eight-part documentary “Country Music” will air starting Sept. 15 on PBS. Although conceived years before the present debates, the film tackles the multifaceted, sometimes contradictory roots of a musical form that is distinctively American.

Why We Wrote This

Country music’s twangy reputation has long rested on white guys singing about lonesome hearts. But as a new PBS series notes, country’s roots go back to the influences of the black banjo and white fiddle.

“It comes from what we call our first episode, ‘The Rub,’ the friction, in the American South between white and black,” Mr. Burns says. “It is the product of the white fiddle from Europe and the black banjo, and it is suffused with the blues.”

A filmmaker usually drawn to large historical topics, including the Civil War and Prohibition, Mr. Burns was distantly familiar with country music, but when a friend suggested a documentary on the genre, he saw the possibilities. “I make films about subjects I want to know more about,” he says, “and then share the process of discovery.”

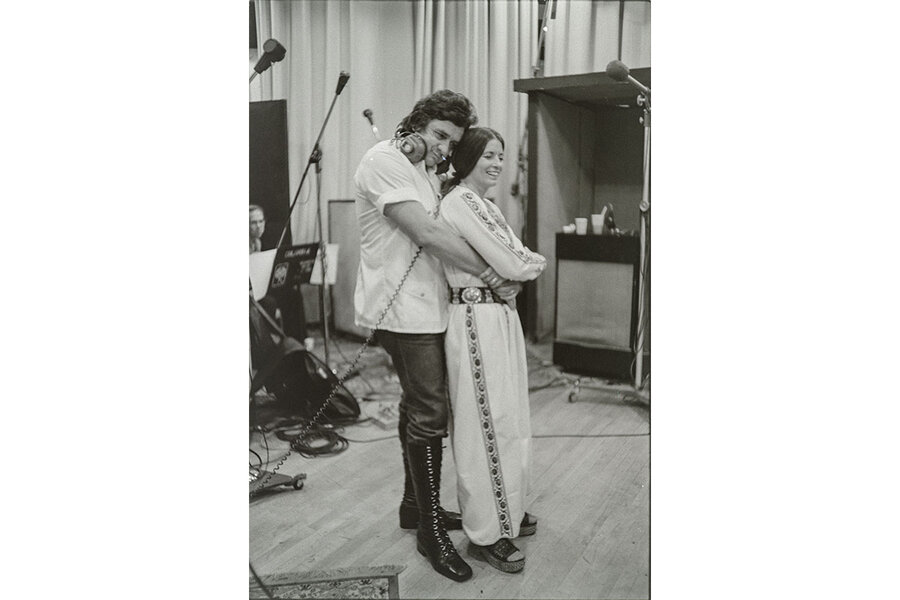

Working with writer and producer Dayton Duncan, Mr. Burns discovered a genre whose roots reflect the nation’s racial diversity. Among the five members of what he calls the pantheon of early country music – A.P. Carter, Johnny Cash, Bill Monroe, Jimmie Rodgers, and Hank Williams – four had African American mentors. “This music that comes down to us as somehow white has at its origin a black story,” he says.

Those who make the music are conscious of the crossing of borders, Mr. Burns says, pointing to the example of soul music titan Ray Charles. “When he’s given creative control of an album ... he chooses to record ‘Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music,’” he says, referring to Charles’ 1962 record that integrated country and soul. “Blacks are listening to supposedly white music, and whites are listening to supposedly black music.”

Mr. Burns lays the blame for the exiling of Lil Nas X from the country charts at the feet of “convenience and commerce.” “You can easily understand why Billboard is going to screw up,” he says, but he encourages listeners to keep their ears open. “Why get stuck in their dialectic when the people have spoken” and made this the longest-running No. 1 song ever – by a gay black rapper.

For his part, Mr. Duncan says that he hopes the documentary helps shed stereotypes, including that of country as “white guy-only” music. “The Carter Family was two women and a guy, and the guy only sang a little,” Mr. Duncan says, referring to pioneers A.P. Carter; his wife, Sara; and his sister-in-law Maybelle.

Mr. Burns notes that Loretta Lynn recorded “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ on Your Mind)” the same year that the National Organization for Women was founded. He compares country music to baseball (the subject of an earlier Burns documentary): Both, he says, are seemingly conservative institutions that can accommodate agents of radical change. “Baseball, this sort of harbinger of every traditional value, is the first real progress in race since the Civil War, when Jackie Robinson [goes] out to play first base on April 15, 1947,” he says.

Although the story told in Mr. Burns’ film mostly wraps up with the 1996 death of Bill Monroe and the simultaneous peaking in popularity of Garth Brooks, some current voices in country hope that the genre will embrace its surprisingly diverse heritage.

“We are experiencing such an exciting time in music right now,” says Staci Griesbach, a singer in Los Angeles who borrows from country and jazz in a new album, “My Patsy Cline Songbook.” “Definitions of musical genres are being questioned, lines are blurring, and the cross-pollination between genres and artists encourages exploration and growth arguably more than ever.”

Mr. Burns identifies the source of the genre’s appeal: love and loss. Country music speaks to human experience, he says. “We hide it with these tropes of pickup trucks and good ol’ boys.”

While conceding the resiliency of such staples, Ms. Griesbach sees a future in which such clichés are less pronounced. “Perhaps we can loosen our grip and find some space to see what surfaces when we provide a little breathing room,” she says.