What ain’t country about ‘Old Town Road’?

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga.

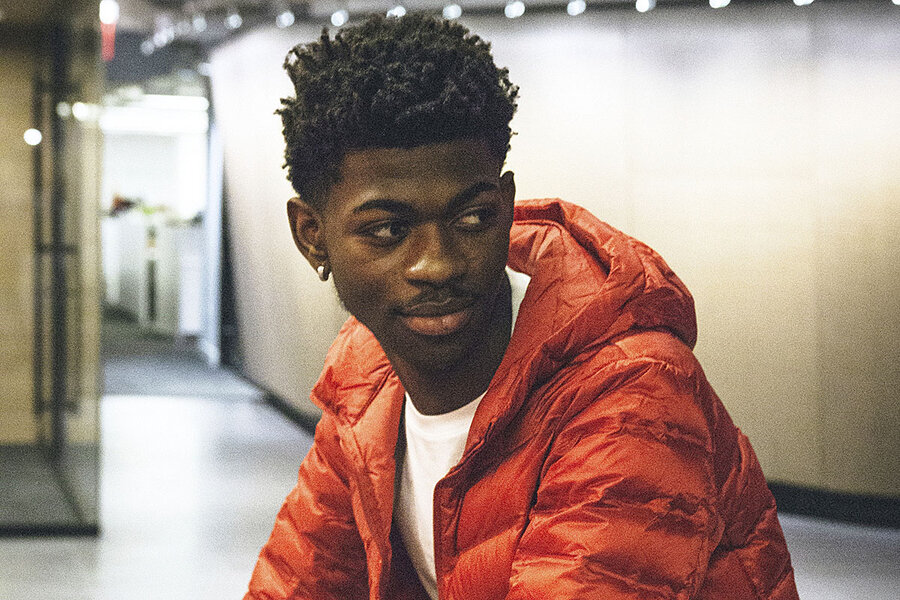

Broke, living at his sister’s house, fighting with his parents after quitting college, 19-year-old Montero Hill of Atlanta put his angst into a song.

The result, “Old Town Road,” is a head-bopping mashup of banjo twangs and cowhand motifs, clocking in at under two minutes. There’s a real sense of longing and comeuppance, but with some meme-ready lines – like “horse” rhymed with “Porsche.”

Known now to the world as Lil Nas X, Mr. Hill wrote what he called “both” a country and a hip-hop song – “country trap,” as his label, Columbia, put it. Goosed by his media savvy on platforms like TikTok, the song broke onto the Billboard country chart at No. 19.

Why We Wrote This

What is a country song? “Old Town Road,” the No. 1 song in America, blends two music genres that in some ways couldn’t be further apart, but which are both based on sense of place, truth-telling, and outsider status.

The song shot to No. 1 on the Hot 100 this week. Only two country songs have topped that chart in the past 30 years. “Old Town Road” would have been No. 3, if Billboard had recognized the track as a country tune.

A week before, citing a lack of “modern country elements,” Billboard yanked it from country charts under pressure from the industry. “Get in line,” the Brothers Osborne fumed.

The rejection raised, for some, new questions about race, culture, and a Nashville-based studio and marketing system that plays on specific references to rural white culture – even as country has grown to play on urban stations from Boston to San Francisco.

For many other music fans – and industry experts – the song also provided a touchstone moment for two music genres that in some ways couldn’t be further apart. But for all of their differences, both are based on sense of place, truth-telling, outsider status, and a shared fascination with the mystery of a good hook.

“This is about commerce – what people want – even more than a controversy about genre and race,” says James Elliott, the legendary songwriting coach at Belmont University, on Nashville’s Music Row. “But is it a country song? [long pause] Well, it’s hard to say what is country anymore.”

Yanking “Old Town Road” may have been a business decision for Billboard, feeling pressure from the $10 billion country music industry in Nashville.

To traditionalists like Mr. Elliott, the song was just too much of a “novelty” and failed to reflect country’s adherence to stringed instruments like the dobro and the banjo.

Yet a lot of artists rushed to Mr. Hill’s defense, including Billy Ray Cyrus, who noted country’s long “outlaw tradition” in which it is a badge of honor to be rejected by Nashville – and, by extension, country radio. (Other famous outlaws include now-revered names like Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, and Willie Nelson.)

Mr. Cyrus called the song “honest,” “humble,” and “infectious,” qualities that for him define country music on an emotional level. He worked with Lil Nas X to create a remix.

“Creatively, I think it’s always a good idea when there’s a hybridization of genres, with cross-cultural conversations going on,” says recording veteran Tom Willett, president of Dark Horse Institute on Music Row. “It makes for some real interesting new music sometimes.”

Boundaries are falling all over the place.

Despite receiving no airplay, the songwriter Kacey Musgraves won the 2019 Country Music Association Album of the Year, as well as Best Country Song and Best Country Album at the Grammys. She’s part of a populist push by industry people to increase airplay of women artists in Nashville. And multiracial singer Kane Brown fought his way back from Nashville rejection by building a YouTube audience so large that it basically forced the industry to sign him. Mr. Brown has become a breakout country artist with hits such as “Lose It.”

“Billboard welcomes the excitement created by genre-blending tracks such as Lil Nas X’s ‘Old Town Road’ and will continue to monitor how it is marketed and how fans respond,” Billboard wrote in a statement to Rolling Stone. “Our initial decision to remove ‘Old Town Road’ from the Hot Country Songs chart could be revisited as these factors evolve.”

This week Country Airplay listed “Old Town Road” at No. 53. Billboard says that chart is based solely on what is playing on country stations – indicating that ”Old Town Road” is picking up some radio time, after all.

Honky-tonk DJs have been spiking the line dancing with hip-hop tracks for a decade. “Hick-hop” artists like Upchurch and Jelly Roll are straight-up hardcore rap – just with Mossy Oak caps and mud-slathered pick-up trucks.

Before he recorded his 9/11 anthem, Toby Keith became the first country artist to rap on a record. Today, artists like Sam Hunt and Luke Bryan experiment with booming hip-hop beats, interspersed with banjo. Truth be told, much country radio fare is nearly indistinguishable from pop.

In that way, Nashville is changing from the inside. Kris Kristofferson, remember, started as a Music Row janitor. New crops of songwriters graduating from the city’s music programs are cross-referencing a variety of styles as they put their mark on country music.

“Right here in Nashville we have a blend of musical styles – pop people and rock people, Kings of Leon, Jack White – and it’s a fun time to be here,” says Mr. Elliott. “But it’s all still about trying to write great songs and melodies and lyrics that move people.”

Indeed, to at least one hip-hop executive, the rejection of Lil Nas X wasn’t as much about race as control – of power, but also musical integrity. Country music has been far more adept than hip-hop in protecting its brand, he says.

“[Lil Nas X] uploaded a song and called it country, and [the industry] said it’s not, and the rest of the world backed off – I think that’s admirable,” says Atlanta-based kingmaker Ray Daniels, the Epic Records executive who helped sign Future in 2016. “They are preserving their culture. They say it’s the good old boy system. I don’t have a problem with that. What I have a problem with is that we [in hip-hop] don’t have our own good old boy system.”

Bob Lefsetz, author of the influential industry newsletter Lefsetz Letter, noted this week that “times changed, the future is here, why can’t the industry and its chart catch up with it? Because radio and labels don’t want it to. ... [In truth,] it’s all about the Benjamins and building careers.”

Of course, the controversy has only helped the song, except perhaps on some country stations. But in the streaming era, that doesn’t mean not being heard. This week “Old Town Road” is on track to reach 80 million streams.

“These kids are growing up today without a genre; streaming is no genre,” says Mr. Daniels of Epic Records in Atlanta. “It’s the new boys. And Lil Nas X is new country.”