'Listen to Me Marlon' is an amazing look at the legendary thespian

Loading...

Marlon Brando died in 2004, leaving behind almost 300 hours of audiotapes of private memories and self-hypnotic musings. In the amazing documentary “Listen to Me Marlon,” which is playing in theaters and will later run on Showtime, British director Stevan Riley intersperses these tapes with a trove of TV and radio recordings. He tracked down rare color footage of Mr. Brando on the set of “On the Waterfront” and shows us snippets of his “Godfather” screen test, in which he wadded his cheeks with cotton, and much else. The result is an unprecedented voyage into the tortuous life of our greatest actor, with the actor himself serving as narrator and navigator, as dissembler and penitent.

Brando changed the face of acting and yet, especially as the years wore on and his weight ballooned, he came to detest his profession. As I wrote about him in my book, “Rainer on Film,” “The gods must have had a good laugh when they created this man; he despised what he did and no one did it better.”

And yet what comes through in this film is his tremendous ambivalence. When he discusses, say, “A Streetcar Named Desire” or “The Godfather,” it’s clear he cared deeply about what he was doing. For his debut movie performance in “The Men,” in which he plays a paraplegic Korean War vet, we see clips of him preparing strenuously for the role in a veterans hospital. On the tapes, he quotes liberally from his acting coach and mentor, Stella Adler, about not being afraid onstage to be who you are.

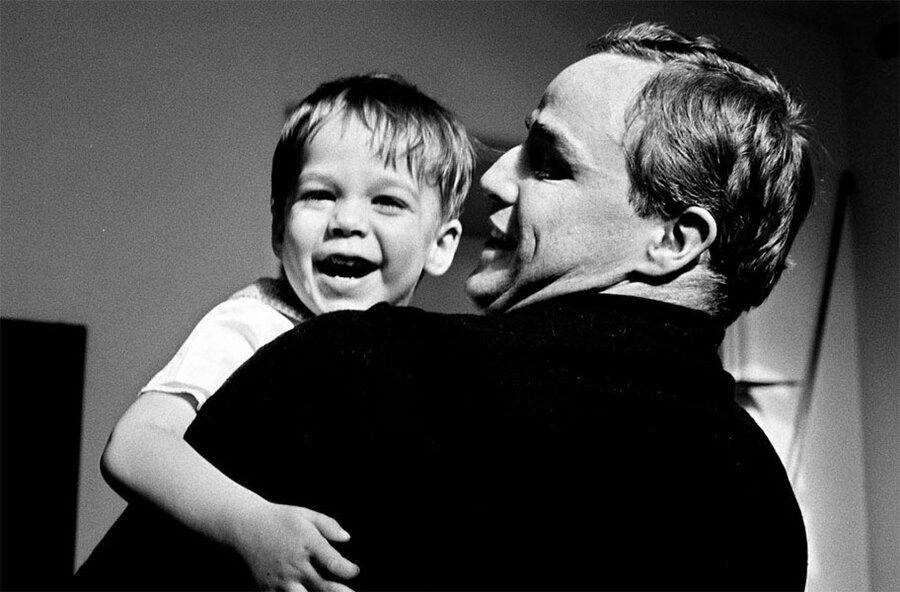

Brando says at one point that “acting is surviving,” and he meant it literally. His childhood was crippling. Of his adored, alcoholic mother, he says wistfully, “I loved the smell of liquor on her breath.” His abusive father was uncaring even after his son achieved worldwide fame. A clip of Brando and his father being interviewed by an off-camera Edward R. Murrow is harrowing – the father mutters his disdain for his son’s acting as Brando’s fake smile freezes into a rictus of disbelief. It was after this interview that Brando refused his father any involvement with his first-born son, Christian (whose tragic life, along with his sister Cheyenne’s, is the death knell that sounds through this movie).

Some of the tapes clearly reflect Brando’s many years in psychoanalysis. “Lying for a living is what acting is,” he says, but then adds, “You lie for peace, you lie for tranquility, you lie for love.” He saw himself as a con man but seemed unable to fully understand how his conmanship could mutate into something higher, into art.

He believed, as do many actors when they become rich and famous, that acting is not a fit profession for an adult. His forays into political activism for African-Americans and Native Americans justified in his own mind his self-worth. He never really comprehended his own genius because greatness as an actor was, for him, no greatness at all.

What does he have to say about his acting in Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris,” perhaps the greatest performance ever put on film? He resented Bertolucci for compelling him to reach way back into his own life. “He felt betrayed,” says Bertolucci, “because I stole from him so many sincere things.”

One should not expect actors to be their own best explainers. Even the finest of them, for all the high-flown talk about technique, operate on an intuitive level that is essentially beyond the reach of rationality. Despite the armature of theories that have built up around the profession – the Method and all else – the kinesthetic essence of acting may be uniquely resistant to self-interpretation.

Brando could provide more emotional levels, more intuitive leaps, than any actor I have ever seen except, perhaps, Laurence Olivier. And yet, even in these audiotapes in which he is basically talking to his most private self – Listen to me, Marlon! – he is mostly clueless about how he achieves his effects. He speaks not so much about what he does but, rather, about how people react to what he does. “People will mythologize you no matter what you do,” he says, and he derives no great satisfaction from this revelation. On the contrary, the public spectacle of being an actor is part of what drove him from the profession, except for the occasional, extravagantly lucrative late-stage cameos in mostly bad movies.

I was torn watching this film. You feel Brando’s pain, and yet it is the fundament of all those great performances. He had the power to do anything he wanted in the movies and he mostly threw it all away. But despite all his hedges and denigrations about the profession, he finally knew what was most important in the actor’s art. “You want to stop that movement of the popcorn to the mouth,” he says, speaking of his audience. “You do that with the truth.” Grade: A (Unrated.)