Trump decries ‘anti-Christian bias.’ Which religions are targeted in US?

Loading...

Donald Trump says God has a “glorious mission” for America.

“We have to make religion a more important factor now,” he said, during remarks at the National Prayer Breakfast at the United States Capitol last week.

Later, at a second event, the president announced the creation of an anti-Christian bias task force to be chaired by Attorney General Pam Bondi. Mr. Trump also said God “saved” him last summer, and that his relationship with religion “changed,” when a gunman began shooting at a campaign event. A bullet grazed Mr. Trump’s ear before he was rushed offstage.

Why We Wrote This

With President Donald Trump creating a task force to stamp out anti-Christian bias, what does religious discrimination in the United States look like today?

Religious liberty has been threatened in recent years, said Mr. Trump.

The new task force will “eradicate” anti-Christian targeting and discrimination in the federal government and around the country, the president said, and will “move heaven and earth to defend the rights of Christians and religious believers nationwide.”

In the first weeks of his term, Mr. Trump has earned both praise and criticism from religious leaders.

“In the aftermath of the Biden Justice Department targeting parents attending school board meetings for possible prosecution and the FBI targeting faithful Catholics as a possible domestic threat, it has never been more important to eradicate all forms of targeting, bias, and discrimination based on faith at the federal level,” said Ralph Reed, chairman of the Faith and Freedom Coalition, in a statement.

The day after his inauguration, the Right Rev. Mariann Budde, the Episcopal bishop of Washington, called on Mr. Trump, sitting in the front pew at the National Cathedral, to “have mercy” on immigrants and transgender children. Mr. Trump later said that Ms. Budde was “not very good at her job.”

And 27 religious groups have sued the Trump administration this week, after an earlier suit by the Quakers. These groups argue that their religious liberty is infringed by changes to immigration enforcement guidance to no longer treat houses of worship as “protected areas.”

While Christians around the world face persecution, aggression against Christians in the United States is rare and happens in isolation, experts say. Some wonder whether the new task force will protect all faiths, pointing to the high rates of antisemitic and anti-Muslim incidents in the U.S. How the Justice Department will define anti-Christian bias, and how it will enforce against that, is not yet clear.

Are U.S. Christians frequently targeted?

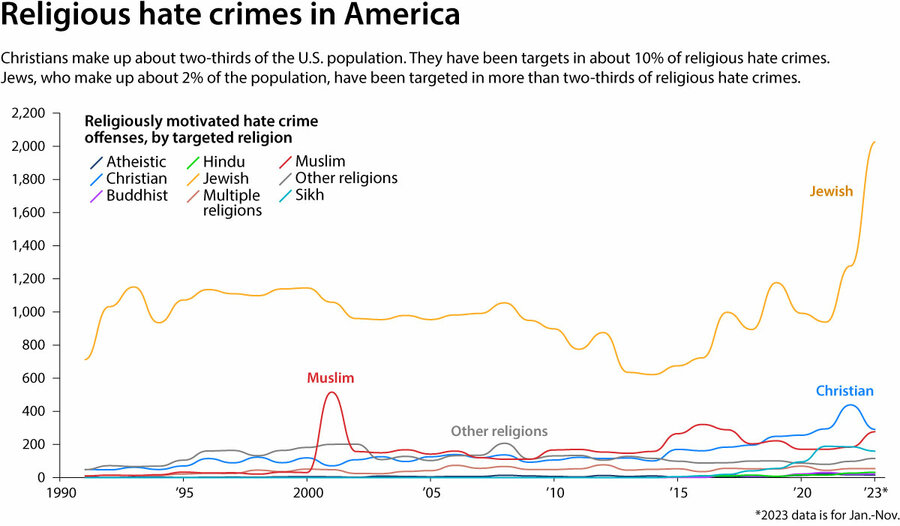

The most common religious hate crimes in the United States are against Jews, followed by hate crimes targeting Muslims. Sikhs also experience more hate crimes than Christians in the U.S., though Jews, Muslims, and Sikhs together make up a much smaller share of the population than Christians. Catholics are the target of more hate crimes than other Christian groups.

Over the past five years, hate crimes targeting Jews numbered more than four times those motivated by anti-Christian bias, according to the FBI hate crime database. Two-thirds of Americans are Christian, and just 2% are Jewish, according to the Public Religion Research Institute in 2024.

To focus the task force on anti-Christian bias deepens the misconception that aggression against Christians is rampant in the country, says Amanda Tyler, executive director of Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.

“These claims also undercut the very real Christian persecution that happens in countries around the world,” says Ms. Tyler.

What is religious privilege?

Religious freedom is constitutionally protected. Religious privilege is simply a social advantage, says Ms. Tyler. And it’s one that Christians often enjoy in the U.S., which is still majority Christian. Some people interpret religious freedom to mean religious privilege or dominance, but that actually runs counter to the principle, she says.

“Just because your particular view is not reflected in law and policy does not mean you are not free to live out ... your religious convictions in the United States,” she says.

Of course, anti-Christian bias exists in some circles, says Dennis Petri, international director of the International Institute for Religious Freedom (IIRF). “There are certainly liberal groups that have a very rigid understanding of the principle of the separation of church and state, of secularism, and of the belief that there should be no public expressions of Christianity whatsoever,” he says.

That can lead to pressure on the government to cut any support to faith-based charities, for example, even though many are engaged in humanitarian work. It’s important not to ignore what may be anti-Christian bias, but also not to exaggerate it, Dr. Petri says.

And, there have been hate crimes against houses of worship. A shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, killed nine people. In 2018, 11 people were killed in an attack on a Pittsburgh synagogue. And of course, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on Sept. 15, 1963, killing four girls.

Mr. Trump has received praise for last week’s announcement of the task force from politicians and Christian leaders who say anti-Christian bias is an underacknowledged problem.

“It’s never been a tolerance for people of all faiths. There has almost always been an outright hostility that is shown towards people of the Christian faith,” said House Speaker Mike Johnson on a recent podcast episode with Tony Perkins. Mr. Perkins is a former Louisiana state lawmaker and current president of the Family Research Council. Both he and Mr. Johnson said the president’s announcement was a step in the right direction.

Does religion get special protections?

Because religious freedom is enshrined in the Constitution, government restrictions on the practice and expression of faith in the U.S. are rare. However, societal discrimination by nonstate actors has increased in recent years, according to a report by the International Institute for Religious Freedom.

“The United States really shows that secularism doesn’t need to be anti-religious,” says the IIRF’s Dr. Petri.

Religious and secular voices can be represented in the public sphere, he says, something he sees as part of healthy democratic debate. That plurality is one protection against a counterintuitive challenge to religious freedom: politicization of the concept.

When certain groups use the term “religious freedom” to promote their particular agendas, “it takes away a lot of the credibility for religious freedom,” he says.

And, in instances around the world in which the state represses a certain religion, it encourages acts of violence by other actors against that particular group.

In the case of the new Department of Justice task force, Ms. Tyler is concerned it might enforce a particular theological view.

It’s not the government’s job to endorse a particular denomination of Christianity, or give support or protection to any one faith, she says. “The government’s job is to stay neutral when it comes to religion and to enforce our laws, including our civil rights laws and protections, to protect everyone from persecution and bias.”