Free movement or privacy? Pandemic forces new trade-offs.

Loading...

| Amherst, Mass.; Basel, Switzerland; and Seattle

When Jung Won Sonn flew from London to Seoul over Easter, he traded one freedom for another.

“In the U.K., you are allowed to go out just once a day, and if you go to the park and gather in a group of four or five people, police will approach you and disperse the crowd,” says Professor Sonn, an associate professor at the Bartlett School of Planning, University College London. “That’s not democracy.”

Now in Seoul, Professor Sonn enjoys freedom of movement, but he had to download a pair of smartphone apps that would keep the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Ministry of the Interior and Safety informed of his whereabouts.

Why We Wrote This

In times of crisis, protecting human rights often involves a delicate balancing act. In a pandemic, it can mean exchanging some of our privacy for freedom of movement.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

South Korea’s pandemic response has been honed through past exposure to SARS and MERS outbreaks. For one thing, testing is widespread, fast, and convenient. Public health authorities have also marshaled the country’s sophisticated tech infrastructure – widespread GPS-enabled mobile phones, cashless payments, and closed-circuit video cameras – to monitor the population.

Along with Taiwan, which takes a similar approach, South Korea has drawn praise for containing the virus while avoiding strict lockdowns. This system has also likely spared lives: South Korea, whose population is about 50 million, has reported about 240 deaths. By contrast, Great Britain, population 65 million, has seen more than 26,000 deaths.

But this model comes with its own costs. In Korea, those suspected of carrying the virus are expected to have their phones on them at all times so that authorities can locate them and inform anyone who may have been infected, a method called “contact tracing.” (Authorities may also call at random during waking hours.) And the locally broadcast text messages that share the age, gender, and location data of those who have tested positive for the virus are fueling public shaming.

Countries seeking to relax their lockdowns by emulating South Korea’s approach face a delicate balance between freedom of movement and freedom of privacy. On one hand, stay-at-home orders inhibit citizens’ rights to assemble and engage in commerce. On the other, to lift those restrictions while monitoring the spread of the virus would require newly invasive forms of state surveillance.

“We are making a hard choice between two undemocratic options,” Professor Sonn says.

Who is mobilizing “disease detectives”?

In the United States, much of the burden for contact tracing has been carried by state and local governments, working under guidelines provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies. Since the novel coronavirus pandemic has placed about 65% of the U.S. population under lockdown, some states have organized armies of “disease detectives.” But the disparities between states remain vast, as the Monitor’s Simon Montlake reported last month.

Silicon Valley hopes to narrow that gap. Apple and Google announced in an April 10 joint statement that “in the coming months,” the companies would be developing an opt-in “Bluetooth-based contact tracing platform.”

Germany and France initially rejected this system, seeking a more centralized approach called Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing. Germany and Italy eventually came around to Google and Apple’s approach, while France, Great Britain, and Spain are pursuing their own apps.

Advocates of centralizing data cite the scientific value of large datasets. Critics worry that governments will use the data for other purposes.

“Google and Apple got it right this time,” notes Jovan Kurbalija, head of the Geneva Internet Platform, a Swiss initiative. “For the tech industry, COVID-19 also poses a unique opportunity to get out of the ‘tech-lashing’ phase of avoiding taxes and not dealing properly with users’ data.”

He expects that Apple and Google’s approach, which protects data by leaving it on users’ devices, will prevail because they already have billions of users worldwide. What remains to be resolved, he says, is the extent to which the contact-tracing apps being developed in Europe and beyond will be compatible with the contact-tracing systems that are expected to be native to Android and iOS devices.

Does it work?

Contact tracing long predates the mobile phone. The concept emerged in early modern Europe in an attempt to limit the spread of syphilis among sex workers. Before the coronavirus pandemic, contact investigators have sought to limit STDs, tuberculosis, Ebola, and other perceived threats to public health.

Modern technology opens up new avenues for authorities to track and limit the spread of a disease, but it still faces challenges.

Contact tracing apps require usage by at least 40% to 60% of the population before they are useful. This raises the question whether the voluntary approach favored in Europe will yield the same results as compulsory methods in Asia.

What’s more, Bluetooth technology is not flawless. For example, the virus does not penetrate walls. Bluetooth signals do, which may lead to a false positive. Connectivity problems – familiar to anyone who uses a Bluetooth speaker – could return a false negative.

“Beware of the false reassurance that an app can provide,” says Luciano Floridi, director of Oxford’s Digital Ethics Lab. “No bad news is just that. ... It doesn’t mean everything is OK. Of all the weapons we have, this is probably the smallest and least important. The app, if it is useful, is only useful within a much bigger strategy that is medical and social. Concentrate on the wider strategy.”

Professor Floridi worries that governments could make the mistake of linking incentives – such as the right to socialize or work – to ensure enough people download the apps. This, he says, risks dividing the population into those who can afford a smartphone and have the digital skills to manage the app and those who don’t.

“That would be a disaster,” he says. “The privacy problem could be solved if we do the right thing. It is the social justice that worries me.”

An invasion of privacy?

Digital contact tracing is no substitute for human health care workers and medical testing, cautions Margaret Hu, an associate professor at Washington and Lee University School of Law. “If you don’t have widespread testing, and if you don’t have accurate testing,” she says, “are you, through this warning system, going to have a very large rate of false warnings or under-warnings?”

And, Professor Hu notes, state powers enacted during extraordinary times have a way of being repurposed once the crisis passes. “Emergency state powers lend themselves to normalizing surveillance in day-to-day governance,” she says. “If you don’t fight to protect the liberties, freedoms, and privileges afforded by the Constitution, it’s very hard to claw them back once those rights are ceded to the government.”

If done right, digital contact tracing could be compatible with privacy rights, argues E. Glen Weyl, founder and chairman of the RadicalxChange Foundation, a nonprofit focused on improving democratic systems and market economies.

“There are ways to implement that sort of thing that are not major problems for civil liberties,” he says. He describes a decentralized contact-tracing system similar to the one used in Taiwan. “No individual person’s location history is ever stored anywhere other than on their own private device. This is not rocket science.”

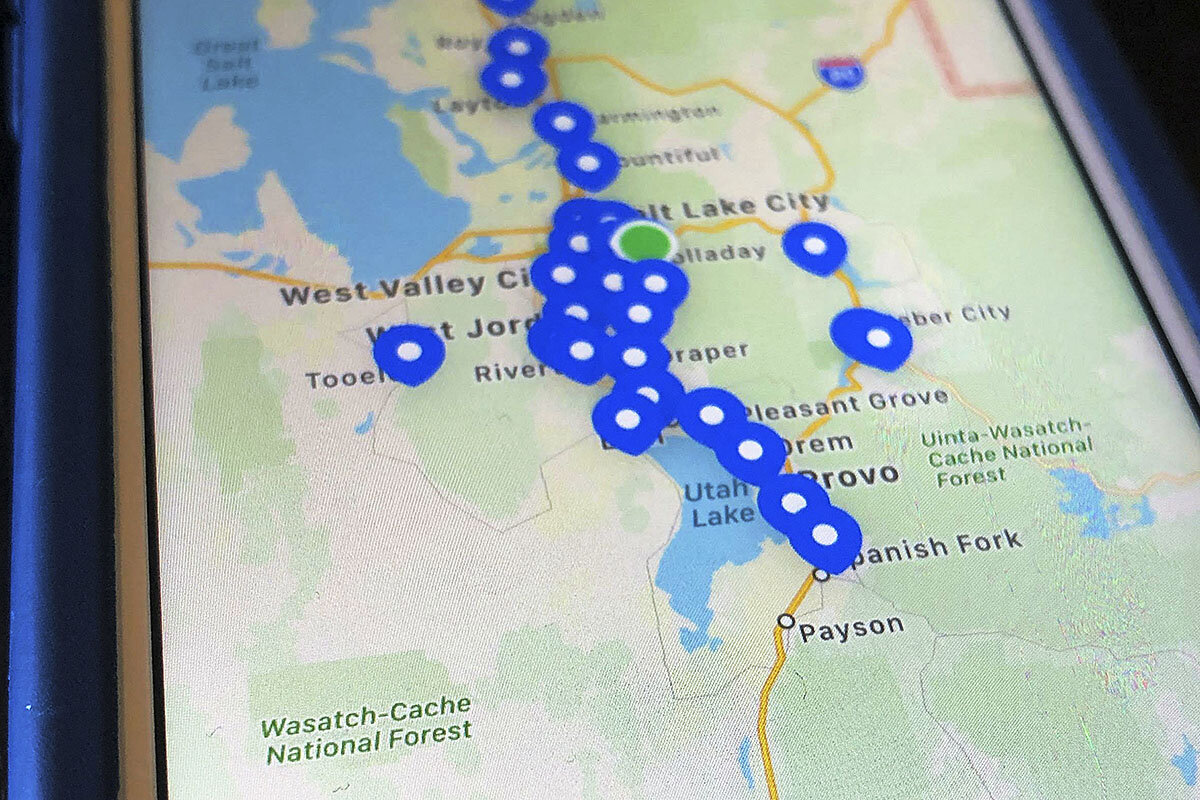

Such a system would share only certain location data, which would be compiled into heat maps that could be used to locate potential outbreaks. “There is not a fundamental impediment here to doing it in a way that is consistent with American values,” says Mr. Weyl.

Professor Sonn says that on the balance he thinks South Korea’s test-and-surveil approach is best, but he cautions against binary thinking. “Most journalists are using this dichotomous framework of ‘surveillance versus democracy’ because it’s familiar,” he says. “Once you get a framework, you tend to use it in new situations.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.