How the Great Barrier Reef is going from bad to worse

Loading...

Though the corals of Australia's Great Barrier Reef historically have managed to adjust to gradually warming seawater of the summer months, they will likely lose their defenses when the ocean warms overall in the near future, say scientists.

This was the latest finding from a team of American and Australian coral reef experts from James Cook University, the University of Queensland, and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

These same scientists recently reported that their aerial surveys of some of the 3,000 coral reefs that make up this iconic natural wonder off Australia's northeastern coast have showed that coral bleaching this year is the worst that has ever been observed. This is largely due to a recurring weather event known as El Niño, a storm system that is expected to become more frequent and more severe in the future.

"I agree that El Niño is a natural variability; it's a part of nature, but that variation in patterns and temperatures is superimposed upon a trend of warming," Scott Heron, a NOAA coral reef scientist based in Australia, tells The Christian Science Monitor in an interview. "There are ups and downs, but now there are just higher ups than ever before, and the downs are not as low," he says.

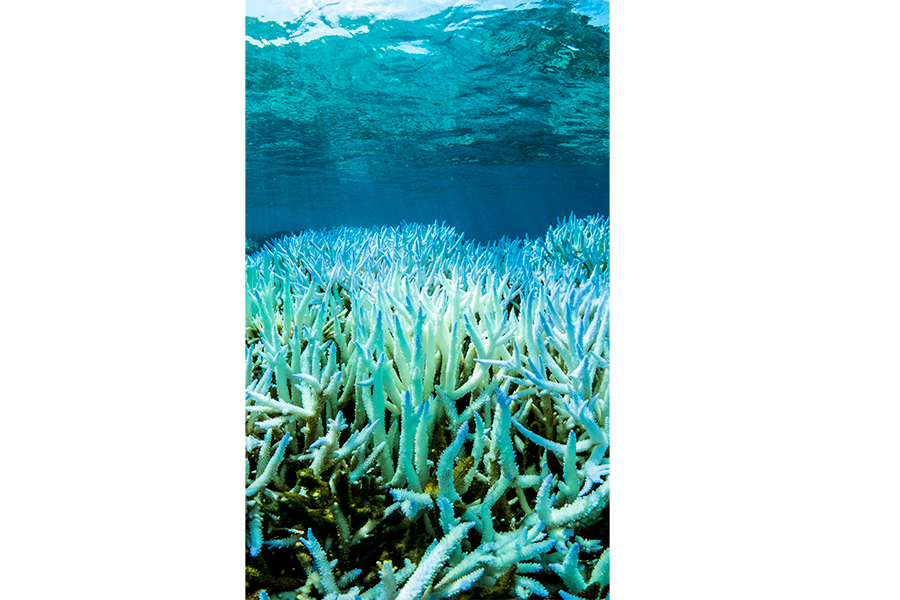

Coral bleaching happens when ocean temperatures rise to a point that zooxanthellae – tiny algae that live on corals and provide them with nutrients and their radiant colors – leave their coral homes, thereby rendering coral white or "bleached." When corals go without zooxanthellae for too long, they die. This affects about a quarter of marine species that depend on coral reefs for shelter, and the humans who depend on those species for their livelihoods.

This year's is the third major bleaching event in recent history for the 2,300-kilometer-long Great Barrier Reef, which is home to one of the most diverse ecosystems in the world. But this one is much worse than the bleaching events that occurred in 1998 and 2002, say scientists who recently found bleaching in almost 1,100 kilometers of northern barrier reef, from the island of New Guinea to the Australian coastal city of Cairns. The researchers estimate that 30 to 50 percent of the corals there are already be dead.

Now the scientists have found that the coping mechanism barrier reef corals use to prepare themselves to face warm summer water is also under threat from global warming, and from human activities such as agriculture, shipping, and fishing.

"As temperature warms, the evidence is that this protective mechanism will no longer function," C. Mark Eakin, a scientist with NOAA Coral Reef Watch, tells the Monitor in an interview.

In a paper published Thursday in the journal Science, Dr. Heron, Dr. Eakin, and their team report on years of study of how weather patterns affect coral, including an analysis of 27 years' worth of satellite data on surface sea temperatures.

By looking at satellite temperature data and recreating the weather patterns in tanks of corals in a lab, the scientists found that they were healthiest during a weather pattern where there is a period of warming in early summer, followed by a quick dip in temperature before the weather reaches a summertime peak.

"That little pulse of warming followed by cooling period is a key shape," says Heron. The cooling period forces corals to create proteins that protect them from the stress of heat, so that by the time it gets warm for good, the invertebrates are somewhat used to it.

"The cool relaxation in between the prepulse and peak is helping the coral to have the time to get their ducks in a row before they prepare for the stress that's to come," explains Heron.

But with temperatures expected to continue to rise, corals will likely not get enough of that cool dip.

It is possible that barrier reef corals will adapt to warmer waters over many generations, but no one knows how long that could take or if there will even be any coral left to do the adapting.

The most viable immediate remedy, say paper authors, is to reduce the carbon emissions that cause warming and restrict other human activities near the reefs that add more stress, including runoff from agriculture, unsustainable fishing practices, and physical damage to the reef from ship groundings.

"These are all human stressors on reef that have to be minimized or eliminated for reefs to be able to bounce back from these bleaching events, even in a decade or two," Eakin says.