How you can help find ripples in spacetime

Loading...

An idle home computer could find the next evidence of one of the largest scientific discoveries of the last century: gravitational waves.

Last month, scientists announced the first detection of the cosmic phenomenon that astrophysicists proclaim will revolutionize our understanding of the universe. First proposed 100 years ago by Albert Einstein, gravitational waves are ripples through spacetime caused by far-off, violent collisions.

The waves were first detected on September 14, having rippled through spacetime for 1.3 billion years before reaching Earth. Researchers are eager to see them again – and they’ve recruited citizen scientists to help.

In 2005, scientists launched the Einstein@home project to help analyze the massive amounts of data collected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which recorded the waves that the collision generated.

The Einstein@home screen saver automatically downloads and searches chunks of LIGO data and sends the results back to a central server. But the project has come up empty handed over the last 11 years.

That could soon change now that the project has expanded its analysis to data collected by the upgraded observatory, known as Advanced LIGO, between September and January.

The upgrade vastly increased the amount of sky that LIGO could scan for signals and led to the discovery of gravitational waves, which was announced Feb. 11.

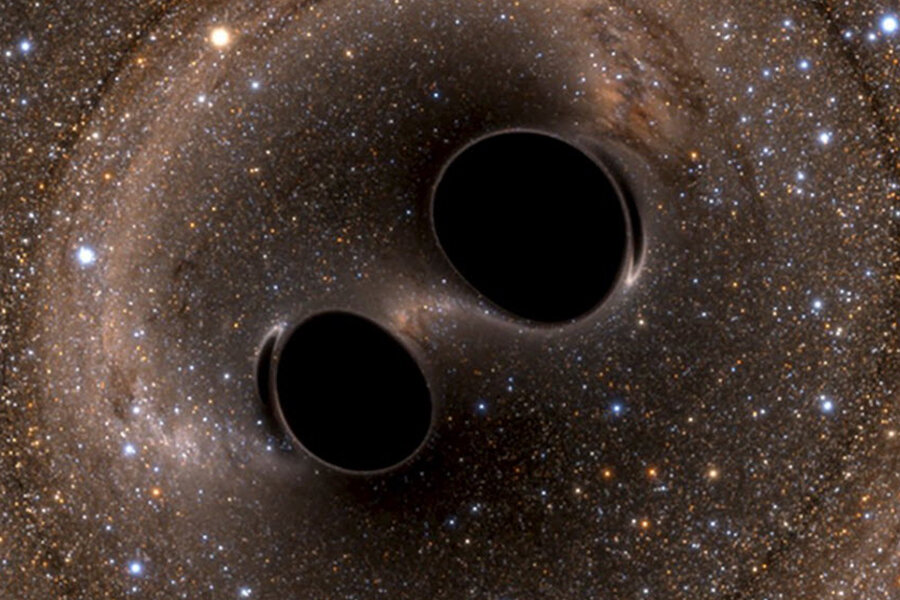

Einstein@home isn’t designed to look for dramatic sources of gravitational waves, such as the black hole merger that LIGO detected in September. Instead, the program looks for quieter signals that might be emitted by fast-spinning objects – such as some neutron stars – that could help scientists better understand the remnants of supernova explosions, some of the least well-understood objects in astrophysics.

“Einstein@home is used for the deepest searches, the ones that are computationally most demanding,” Maria Alessandra Papa, a LIGO astrophysicist based in Hannover, Germany, told the journal Nature. The hope is to extract the weak signals from the background noise by observing for long stretches of time. “The beauty of a continuous signal is that the signal is always there,” she added.

Einstein@home is modeled off of SETI@home project, which searches radio-astronomy data for messages sent by alien civilizations.