Astronomers spot glimmer of a galaxy that dates back to universe's infancy

Loading...

A team of astronomers say they have discovered a hot, star-popping galaxy that – at 13.4 billion light years away – is much farther than any galaxy previously identified, both in time and distance.

Using a technique that has raised some skepticism among rival astronomers, they say they’ve identified a galaxy from a time when the universe was only about 400 million years old. That’s a time period commonly believed to be impossible to observe with today’s technology.

The discovery far surpasses previous records for distance and time, and may be farthest that can be seen until a new space telescope is launched, the astronomers report in a paper published Thursday in Astrophysical Journal.

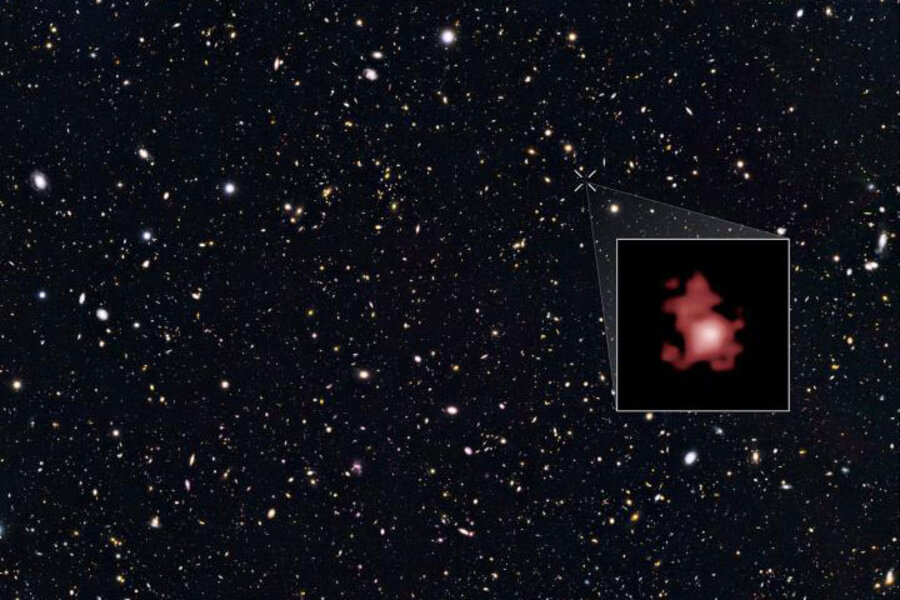

Using a light light wave signature detected by the Hubble Space Telescope, the astronomers were able to produce a photo of this galaxy that is fuzzy and even deceptive in color. Though really hot enough to burn bright blue, it appears darkish red and fuzzy in a photo because the light has traveled so long and far enough that it has shifted to the very end of the color spectrum, to a dark reddish color.

The galaxy’s photographed fuzziness masks a rate of star formation that is 10 times more frenetic than our Milky Way, according to study co-author Gabriel Brammer, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute.

“It really is star bursting," Dr. Brammer told AP. "We're getting closer and closer to when we think the first stars formed ... There's not a lot of actual time between this galaxy and the Big Bang."

The new galaxy, named GN-z11, is right at the edge of Hubble's limits.

“We’ve taken a major step back in time, beyond what we’d ever expected to be able to do with Hubble. We managed to look back in time to measure the distance to a galaxy when the Universe was only three percent of its current age,” says Pascal Oesch of Yale University, the paper’s lead author, in a statement.

Astronomers determine distance of an object by calculating how much the light changes from blue to red, a measurement known as redshift. The new galaxy has a red shift of 11:1, a milestone that goes bar beyond the previous redshift of 8.68, or about 580 million years after the Big Bang. For a long time, competing teams of astronomers hoped to reach a redshift of 9, about 580 million years after the Big Bang.

But the new discovery went far beyond that goal, surprising even the researchers, Dr. Oesch says.

They discovered the galaxy by jettisoning the traditional method of using a standard light wave signature marker, with the spectrum of light measured precisely using a ground telescope.

Instead, they looked beyond that bright line to a longer, but also messier light wave spectrum using what is considered a rougher tool, Garth Illingworth, another co-author at the University of California Santa Cruz, told AP.

Richard Ellis, a competing astronomer at the European Souther Observatory, who found the galaxy that held the previous record, was more skeptical.

The light signatures used by Oesch’s teams are “noisier and harder to interpret” and may overlap with competing nearby stars and galaxies, he says.

For the next galaxy to be as visible as it appears in the photo, it would have to be three times brighter than typical galaxies, he told AP in an e-mail.

But Oesch responded that his team ensured that “this was as clean as possible a measurement” with little contamination. The technique they used is starting to become standard he said.

The new galaxy allowed the researchers to peer much farther back in time, the researchers say.

“The discovery of GN-z11 showed us that our knowledge about the early Universe is still very restricted. How GN-z11 was created remains somewhat of a mystery for now. Probably we are seeing the first generations of stars forming around black holes?” says team member Ivo Labbe, of the University of Leiden, in the statement.

If we could get closer, and journey far back in time, we’d likely see extremely bright blue, young stars and messy, just-formed galaxies, Dr. Illingworth says.

The new discovery could be the standard-bearer for the oldest and farthest galaxy for at least the new few years, the astronomers say, until the next NASA space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, launches, likely in 2018.

Dimitar Sasselov, an astronomer at Harvard University, who wasn’t part of the research, called the discovery exciting and interesting. “Seeing and understanding the first galaxies and the first stars is an essential part of our origins story,” he told AP.

This report contains material from the Associated Press.