How digital 'tree of life' embodies the potential of open science

Loading...

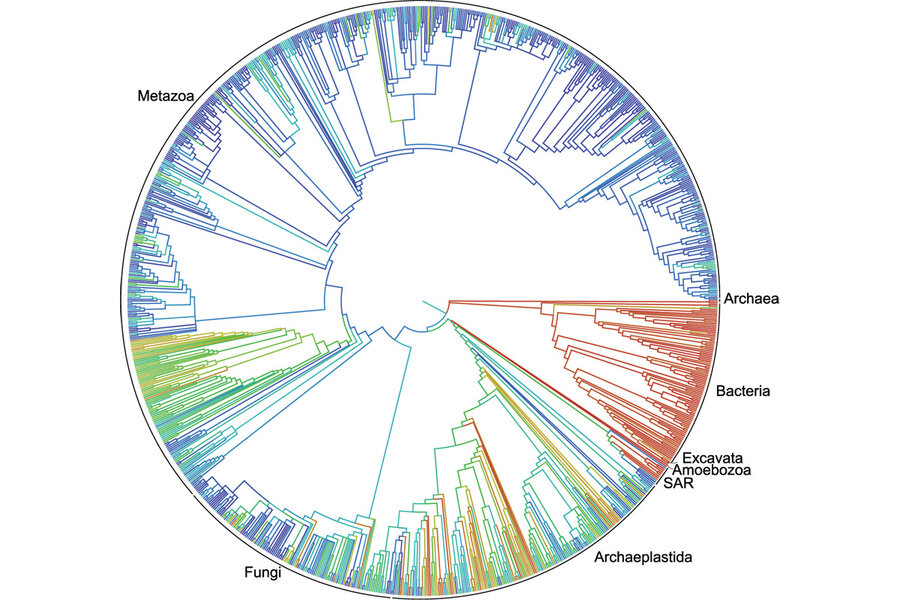

Scientists over the weekend released the first draft of a digital “tree of life” that visualizes everything we know about the planet’s roughly 2.3 million named species and how they are related to one another.

The project, a collaborative effort among scientists from 11 organizations, traces relationships between living things as far back as the dawn of life on Earth 3.5 billion years ago. The result is an online resource that encompasses tens of thousands of smaller evolutionary trees published over the years in a format that anyone can use or edit – an effort that illustrates on a broad scale how open-science principles and digital technology can bring together information to expand understanding of a complex subject.

"Twenty-five years ago people said this goal of huge trees was impossible," said co-author Douglas Soltis, a genetics professor at the University of Florida. "The open tree of life is an important starting point that other investigators can now refine and improve for decades to come."

Open science advocates promote “the free, immediate, availability on the public Internet of those works which scholars give to the world without expectation of payment,” according to the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, an international alliance of academic and research libraries. Through open science, users can “read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full text of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software or use them for any other lawful purpose.”

As writer Rose Eveleth explains in The Atlantic:

Open-access publishing advocates want papers to be available to anybody, open-data supporters want data to be downloadable, and those arguing for open source want the software scientists use to be shared with everyone.

“The idea is simple,” she continues. “The more people who have access to papers, data, and software, the better it is for the world.”

The movement has seen growing support within the scientific community. In November, CERN – the European Organization for Nuclear Research – made public for the first time the data from experiments its scientists conducted using the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator. That same month, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation said that come January 2017, any research it funds would have to be published only in journals that offer immediate open access.

Critics of the movement – many of whom belong to established institutions and publications – say the model is not economically sustainable.

“I would love for it to be free,” Alan Leshner, executive publisher of the journal Science, told The New York Times in 2012. But “we have to cover the costs,” which hover around $40 million a year to produce and publish his nonprofit flagship journal.

The open tree of life, however, focuses on an alternative angle to the discourse around open science: the practical applicability of shared information. For the researchers behind the project the goal is to collect and analyze existing data on all the world’s known life forms and use that knowledge toward advancements in the study of life, disease, agriculture, and other industries.

The tree of life isn’t “just for figuring out whether aardvarks are more closely related to moles or manatees, or pinpointing a slime mold's closest cousins,” according to the researchers’ statement. “Understanding how the millions of species on Earth are related to one another helps scientists discover new drugs, increase crop and livestock yields, and trace the origins and spread of infectious diseases such as HIV, Ebola, and influenza.”

The only way to do that, they said, is to fill in the gaps in our knowledge using data and information for millions of species that researchers around the world are discovering, naming, and collating every day.

"There's a pretty big gap between the sum of what scientists know about how living things are related, and what's actually available digitally," said principal investigator Karen Cranston of Duke University. "It's critically important to share data for already-published and newly-published work if we want to improve the tree."