Prehistoric 'cow' may have been the first to walk on all fours

Loading...

This week, a new study, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, reveals that a pre-reptile, known as Bunostegos akokanensis, may have stood upright on all fours. The findings suggest that the creature, approximately 260 million years old, could be the earliest known animal to have done so.

Previous estimates placed the earliest evolution of walking creatures at 210 million years ago, with the 2000 discovery of the two-legged Eudibamus lizard.

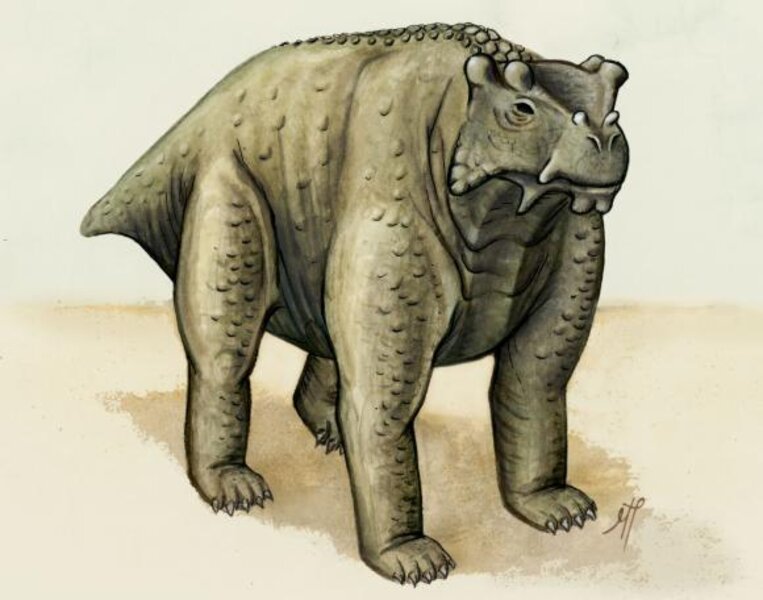

The creature, which according to projections resembled a pit bull or perhaps a small cow, belongs to the pareiasaur group. These were herbivores that lived during the Permian Period nearly 300 million years ago, and included species such as the Dimetrodon, which had a lizard-like body and a "sail" fin on its back, or the Lystrosaurus, a herbivore with tusks. Among these counterparts, the Bunostegos akokanensis would have fit right in.

“Imagine a cow-sized, plant-eating reptile with a knobby skull and bony armor down its back,” said co-author Linda Tsuji, of the Royal Ontario Museum. She and her co-authors discovered the fossils in Niger with a team of paleontologists in 2003 and 2006.

During the Permian, the last geological era of the larger Paleozoic, many animals had upright or semi-upright hind limb posture - a bone structure also seen in some modern lizards. Initial research seemed to indicate that the Bunostegos would also have short and wide-spread forearms, yet examination of its forelimbs yielded an entirely different conclusion: The animal stood differently from its counterparts. It had legs which were entirely beneath its body.

"A lot of the animals that lived around the time had a similar upright or semi-upright hind limb posture, but what's interesting and special about Bunostegos is the forelimb, in that its anatomy is sprawling-precluding and seemingly directed underneath its body – unlike anything else at the time," said lead author Morgan Turner in a statement. She was involved with analyzing the creature's bones while studying at the University of Washington, and is now a graduate student at Brown University.

Other evidence appears to suggest that because of the Permian’s geography, the Bunostegos lived largely by itself in an extremely arid habitat.

“Bunostegos was an isolated pareiasaur [large herbivore],” Turner said.

Its long limbs enabled it to trek for long distances in search of food and water, say researchers, and would have been possibly more effective than a sprawling posture, in which the forelimbs do not match up directly underneath the shoulders. The Permian was much drier than previous geological eras due to rainforest collapse, and the supercontinent of Pangea, Bunostegos’ home, would have been dominated by extremes in temperature fluctuation. Over time, plants became more drought-resistant, and some reptiles adapted by becoming more warm-blooded.

“Posture, from sprawling to upright, is not black or white, but instead is a gradient of forms,” Turner said. “There are many complexities about the evolution of posture and locomotion we are working to better understand every day. The anatomy of Bunostegos is unexpected, illuminating, and tells us we still have much to learn.”