Butterflies in space? Hubble beams back specular image of iridescent 'wings'

Loading...

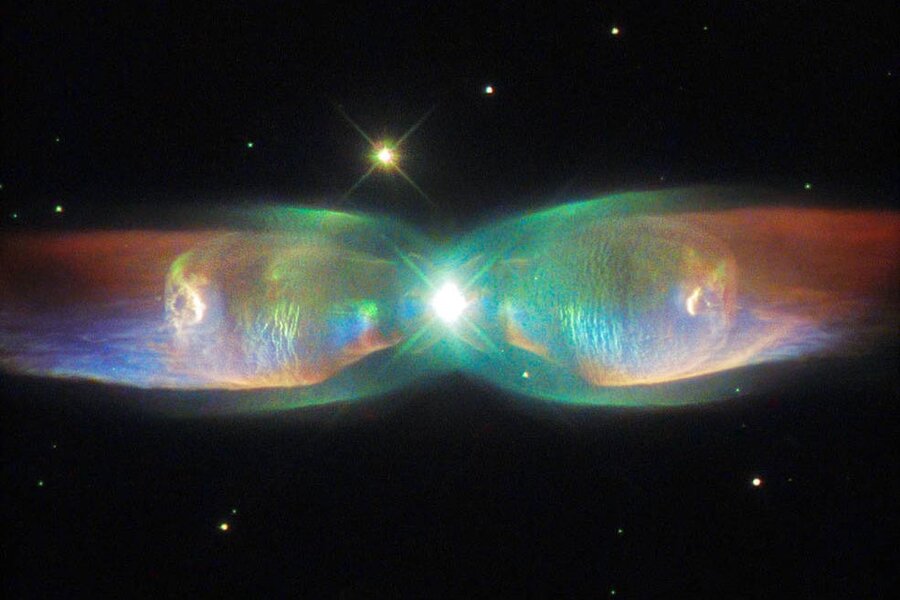

In space, stardust can mimic familiar Earthly shapes. An example of this was recently beamed back from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope: stunning images of a butterfly nebula.

The butterfly in the cosmos is actually called the Twin Jet Nebula, as well as the much less descriptive (to non-astronomers) PN M2-9.

The phenomenon is created through a bit of good fortune, NASA acknowledges, as well as a large amount of dust surrounding a slowly dying larger star, accompanied by a smaller star, in this case a small white dwarf, which come together with the effect of two shimmering wings. Both "wings" stretch from the central two-star system. The winged shape is believed to be created from the binary stars orbiting a common mass and fueled by two enormous gas jets speeding through space at 621,400 mph, each jet on a trajectory that is curved with the orbit paths of the two stars. The expansion has been measured, according to NASA, and scientists estimate the nebula was created a relatively short 1,200 years ago.

The glowing and expanding shells of gas clearly visible in the image represent the final stages of life for an old star of low to intermediate mass according to NASA. "Astronomers have found that the two stars in this pair each have around the same mass as the sun, ranging from 0.6 to 1.0 solar masses for the smaller star, and from 1.0 to 1.4 solar masses for its larger companion," NASA reports.

The multitude of colors captured by the Hubble image demonstrates the complexity of the so-called Twin Jet Nebula, which glows because the larger dying star has shed its outer layers, with help from the white dwarf's orbit, revealing a core that illuminates the surrounding action. The image highlights the nebula’s twin shells and tendrils of expanding gas in great detail. Hubble has captured many butterfly nebulae before, and this one in particular was imaged previously in 1997, but Hubble captured PN M2-9 in June of 2015 using newer technology, and therefore capturing greater detail.

PN-M2 9 is in fact descriptively named. The M refers to Rudolph Minkowski, a German-American astronomer who first discovered the nebula in 1947. The PN references the fact that M2-9 is a planetary nebula.

Another research team at the European Southern Observatory in Chile also captured images, released in June, of another butterfly nebula; this one believed to be much earlier in its formation, and therefore that much more important to observe, according to the research team. A lead researcher in its study, Pierre Kervella, called the origin of butterfly nebula "one of the great classic problems of modern astrophysics."

Mr. Kervella said his team is trying to track the evolution of this butterfly nebula. He hopes to determine "how, exactly, stars return their valuable payload of metals back into space – an important process, because it is this material that will be used to produce later generations of planetary systems."