In latest close-up images of Pluto, details of big heart take center stage

Loading...

New close-up images of Pluto, released Friday, as well as fresh information about its atmosphere, are presenting the New Horizons science team with an ever-expanding set of puzzles.

As it hurtles away from the Pluto-Charon system, the spacecraft has returned only about 1 to 2 percent of the data it has on board. And it continues to gather more on the outbound leg of its journey. The craft is now some 2.4 million miles from Pluto.

New Horizons is completing a solar-system reconnaissance effort that saw its first success 53 years ago when Mariner 2 conducted a flyby of Venus – the first successful flyby of another planet in human history.

"I'm a little biased, but I have to tell you that I think the solar system saved the best for last," said Alan Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., and New Horizons's lead scientist, during a briefing Friday.

Among the images the craft has beamed back: the first well-resolved image of Nix, an elongated moon about 25 miles across whose brightness falls midway between that of Pluto and of Charon.

But Pluto's big heart, which the team has informally named Tombaugh Regio, or Tombaugh Region, for the planet's discoverer, Clyde Tombaugh, currently is serving as center ring for the Pluto-Charon show.

The team has identified a concentrated patch of carbon-monoxide ice that has been observed from Earth for years. New Horizons data show that it covers much of the western half of Tombaugh Regio.

"It definitely catches the eye," said Dr. Stern. Across the rest of the hemisphere in which it appears, "there's no other carbon-monoxide concentration anything like this. It's a very special place on the planet."

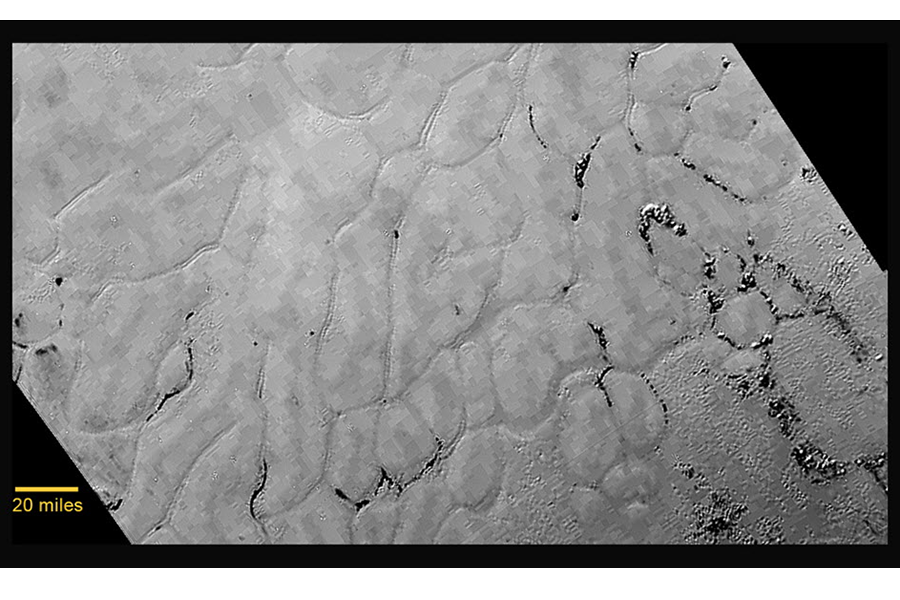

The western region also hosts a broad, crater-free expanse of frozen plain that the science team has dubbed Sputnik Plenum, in honor of the first artificial satellite to orbit Earth. Seen from above, the plain looks as though it's been put together in segments that resemble odd-shaped garden pavers. The segments range in size from 12 to 20 miles across.

The region's lack of craters suggests that it could have formed within the past 100 million years, or "it could be only a week old, for all we know," said Jeff Moore, a planetary geologist at NASA's Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif., and a member of the New Horizons science team.

The giant polygon segments are separated by narrow troughs. Some troughs host collections of mounds and hills that rise above the surrounding plain. Other segments are pitted. The interiors of some troughs appear to be coated with dark material.

Researchers are sorting through possible explanations for these features. Something could be pushing the hills up from underneath, or they could represent knobs of material that stubbornly refuse to bow to forces that may be eroding and lowering the general landscape.

The segments themselves could be surface evidence of convection, Dr. Moore offered. The convection, driven by modest amounts of heat from Pluto's interior, could give the surface layer of nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane ice the look of boiling oatmeal.

Or the segments could form as the surface contracts, forming patterns similar to those in desiccated mud flats on Earth.

"We have various ways to test those ideas," Moore said.

The New Horizons science team also has gotten its first detailed glimpses of data on Pluto's atmosphere, gathered after the spacecraft zipped past the dwarf planet.

Previous measurements from Earth, using stars to backlight Pluto's atmosphere, could detect the presence of an atmosphere only to within 30 miles of the surface and as far out as 170 miles.

Once New Horizons finished its close approach to Pluto, it used the sun to backlight the planet's upper atmosphere, while radio signals sent from Earth probed conditions in the lower atmosphere.

The initial data show that the atmosphere is evenly distributed around Pluto, and it's being carried away by a constant flow of charged particles from the sun, known as the solar wind. Energy from the sun heats nitrogen molecules, which begin to rise into the upper atmosphere. There they are ionized by ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Once the nitrogen is ionized, the solar wind can strip it from the dwarf planet and carry it away.

New Horizons has detected the tail of ionized nitrogen that this process generates – a tail analogous to a comet's tail.

The team has yet to put numbers to the losses, noted Fran Bagenal, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a member of the mission's science team. But models suggest that Pluto's weak gravity and the loss process are pulling nitrogen, the atmosphere's main gas, from the planet at a rate of about 500 tons an hour – a loss rate 500 times larger than the pace at which Mars is losing its atmosphere.

Over Pluto's lifetime so far, that pace would have liberated enough nitrogen to form a layer of nitrogen ice up to 9,000 feet thick, Dr. Bagenal said.

Back on Sputnik Plenum, researchers have spotted dark smudges that could signal wind-borne dust that has settled in the lee of high spots on the landscape.

The material could be evidence of local erosion. The smudges could consist of hydrocarbons, perhaps, that have settled out of the atmosphere. Or the material making up the streaks could originate in plumes or geysers, features also associated with subsurface heat.

No such features have been observed, but data released since Wednesday suggest to the science team that such processes might be active today, replenishing the atmosphere's stock of nitrogen.