Comet ISON now an ex-comet, says NASA

Loading...

Comet ISON sprang into public awareness shortly after its discovery, when its early brightening inspired hopes that it would blaze like the full moon. Quickly dubbed the "Comet of the Century," ISON continued its plunge from the Oort Cloud to the sun, but despite predictions, it failed to brighten much. It buzzed by Mars, where NASA's HiRISE observed it, then it passed through the orbits of all the inner planets before skimming the sun on Nov. 28.

Scientists were riveted. Would ISON's ices melt completely in the sun's heat? Would it get drawn in by the sun's gravity? Or – as amateur astronomers everywhere hoped – would it survive, achieve its early promise, and light up the sky?

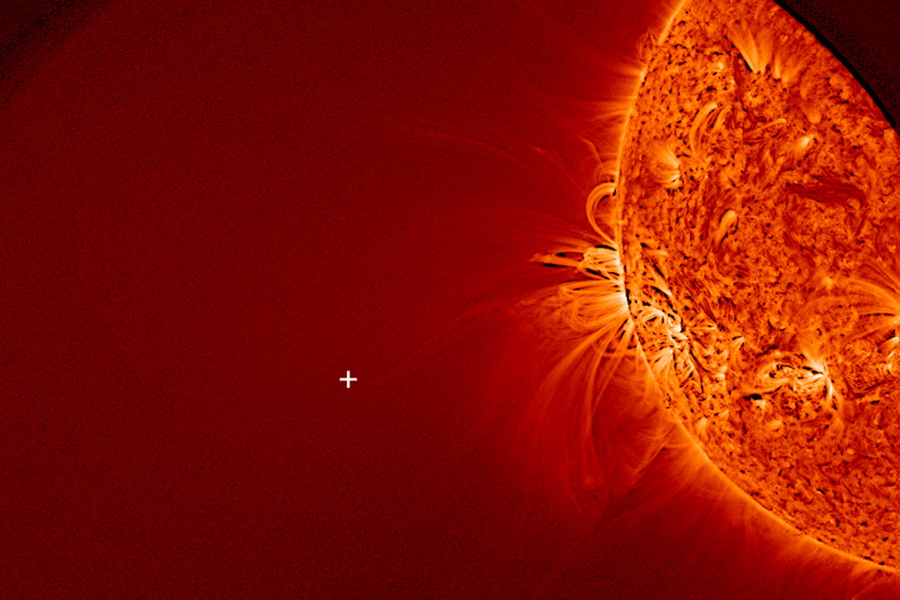

ISON got lost in the sun's glare, ultimately passing less than 1.2 million miles from the sun's surface. Even sun-observing instruments couldn't keep track of it at the most critical moment, since they block out the brightest part of the sun to protect their instruments.

Within hours, astronomers saw something faint emerge from the other side of the sun-blocking disk. Maybe ISON hadn't broken up completely? A glowing cloud continued ISON's parabolic path before dissipating so completely that it's now indistinguishable from interstellar dust, says NASA.

"We see the comet going in, and the object formerly known as ISON emerging from the other side," joked astrophysicist Karl Battams at a meeting of astronomers last week.

The Comet ISON post-mortem

"The comet essentially eroded to nothing," explains Zdenek Sekanina, a senior research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

In fact, says Dr. Sekanina, ISON had ceased to exist as a comet even before it reached "perihelion," the moment of closest approach to the sun. So what happened to ISON, known to scientists as C/2012 S1?

Sekanina has monitored the comet closely for months, comparing it to past comets to try to understand its behavior.

As ISON swept through our solar system, it passed through four or five "cycles" of brightening and dimming, he found. Each cycle corresponded to a source of some ice (or a mixture of ices) sublimating into gas. First was probably carbon monoxide and/or carbon dioxide, he says, converting from dry ice to gas. Then came other ices in turn, until the most stable, water ice, began to turn to water vapor around the time ISON crossed the orbit of Mars.

By mid-November, the nucleus – the "dirty snowball" of ices, dust, and rock that make up the core of the comet's glowing head – had started to fragment severely, says Sekanina. "Parts of the interior became exposed to sunlight," he says, accelerating the rate of ISON's demise. By Nov. 21, one week before perihelion, scientists recorded a huge increase in water vapor production. "At that point," he says, "the nucleus was fragmented into multiple pieces."

Within a few days, all the water vapor and other gases had burned off, he says. With no volatiles left to sacrifice to the sun's heat, the comet began to vaporize its smallest dust fragments and disintegrate into boulders, pebbles, and dust.

"I'd call this the advanced phase of fragmentation," says Sekanina.

"From 3.5 days before perihelion to 3.5 hours before perihelion – that is the time during which, apparently, (the comet experienced) a very intensive fragmentation of the really, really last stuff that remained in the nucleus," he says. And then the fragmentation stopped.

"There was nothing, afterwards," he says. "That was the end of comet activity. The end of fragmentation... After that point, nothing in the comet can change its state."

Comets are constantly changing – growing, shrinking, vaporizing, consolidating – so once nothing "changeable" remained, it stopped being a comet, says Sekanina.

"It was over. About three and a half hours before perihelion, that's it. What you see afterwards is inert fragments and dust. They can be subjected to processes from the sun and corona, sure, but the comet was dead."

Inertia demanded that the "dead" fragments continue on their path around the sun, prompting the term "zombie comet."

With the gases burned away, there was nothing to hold the head of the comet in its typical ball shape, he says. "The sunward tip got ever sharper, indicating that whatever was coming out of the remnant of the the nucleus had no velocity and was subjected only to solar light pressure."

The nose of the comet lengthened into an increasingly sharp needle, made up of the rocks and boulders that were too big to evaporate.

"That's why, one to two hours before perihelion, you see this very faint, narrow extension from the tip," says Sekanina.

And then the comet skimmed through the sun's corona and emerged, continuing to glow in the sunlight, but no longer the master of its own fate. "Comet ISON is dead," announced Dr. Battams at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. "Its memory will live on." NASA says scientists will continue to mine the data obtained from the "unprecedented" number of space-based, ground-based, and amateur observations of ISON during its final months.

Battams, an astrophysics with the Naval Observatory, wrote an obituary for the comet, ending with these words: "Survived by approximately several trillion siblings, Comet ISON leaves behind an unprecedented legacy for astronomers, and the eternal gratitude of an enthralled global audience. In ISON's memory, donations are encouraged to your local astronomy club, observatory, or charity that supports STEM and science outreach programs for children."

Rest in peace, ISON.