Zombie comet: Is Comet ISON really dead? Maybe not.

Loading...

As the minutes ticked by, the palpable sense of disappointment grew in Karl Battams's tweets.

Dr. Battams, a scientist at the Naval Research Laboratory, had for all intents and purposes become the emcee of a highly anticipated celestial event. The alluringly bright Comet ISON, discovered last year, would be swooping within a hair's breadth of the sun, cosmically speaking, on Thanksgiving Day, and if it made it out the other side, we earthlings would all be in for a treat as it swung by Earth a few days later.

Some were saying it could be the comet of the century – a can't-miss event that would make the entire Northern Hemisphere a community of sky-watchers.

But first it had to survive the searing heat of the sun's atmosphere, or corona, unscathed, and much of the sky-watching community was hanging on Battams's @SungrazerComets Twitter feed for updates.

On Thanksgiving Day, as ISON neared the sun, it flared so brilliantly that the Twitterverse essentially responded with a chorus of "oooohs."

And then nothing.

The comet disappeared behind the sun and nothing came out the other side. Like a Viking funeral, Comet ISON had seemingly given onlookers one last spectacular conflagration before heroically plummeting to its demise.

"Sorry we had to break such bad news ...," Battams said in one tweet.

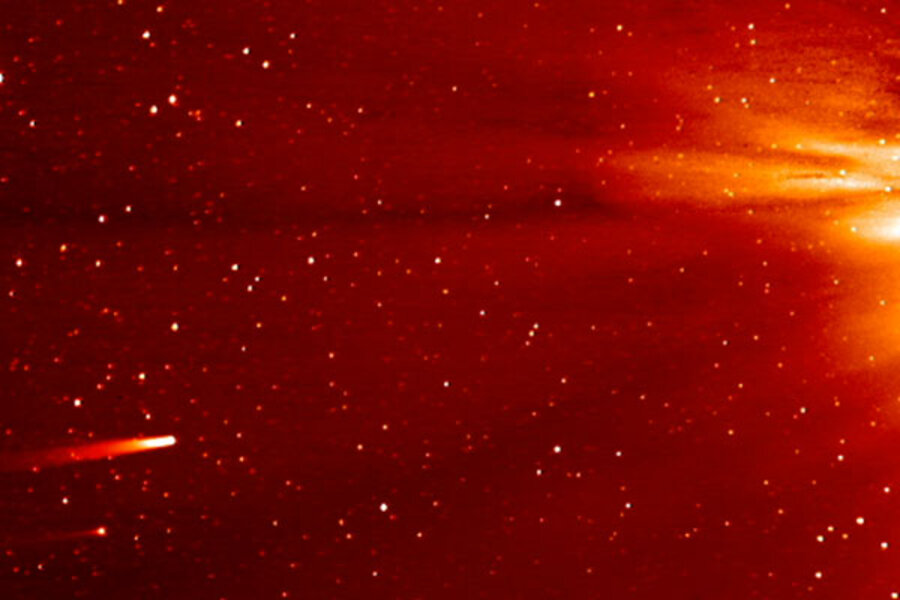

Images were searched and searched by Battams and others for any trace of survival. And there were traces, but nothing that looked organized – that had a clear nucleus.

And then, responding to romantic followers who were holding on to faint hopes: "We do think #ISON is dead but would love to be wrong!"

But that is the thing about comets. That is why stargazers were fixed on ISON since it was discovered last September by astronomers in Russia. Comets are delightfully unpredictable things.

On a Comet ISON Google+ Hangout online chat on Thanksgiving, scientist David Levy had the foresight to quip a traditional line about comets: "Comets are like cats; they have tails, and they do precisely what they want."

Scientists were already abuzz over the opportunity to study Comet ISON as it swept through the sun's corona. How it interacted with the sun's atmosphere could help astronomers better understand both comet and corona.

Now, they have a new challenge: figuring out what the heck happened behind the sun.

That faint trace, after all, did not dissipate as expected but began to strengthen again, suggesting that, perhaps there was still a nucleus – suggesting that Comet ISON is still a comet. With undisguised glee, Battams tweeted Friday morning:

Will Comet ISON survive to give Earth a show, which would begin at its brightest near the eastern horizon near dawn on Dec. 2 and 3 and then tail off as the month passed? No one is foolish enough to guess. Two years ago, Comet Lovejoy made a similar pass by the sun and came out the other side, smaller but still intact. Within days, however, it had broken apart.

Still, the past 24 hours have assured the astronomical community's affection for the comet that wouldn't die.