Dinosaur-era bird tracks: Proof of 100-million-year-old flight?

Loading...

It's all about the fourth toe. While birds and dinosaurs both left three-toed footprints, few dinosaurs have the backward-facing fourth toe that birds use to grab a branch or provide drag during landing. So when Anthony Martin saw the four-toed impression left in an Australian rock more than 100 million years old, he knew he was looking at something special.

"The track seemed familiar, like a face I had seen before but couldn’t quite identify," writes the Emory University paleontologist in a blog describing the find. "Then I realized who it belonged to, and where I had seen many others like it. It was a bird track, remarkably similar to those in the sands and muds of the Georgia coast, made daily by the herons, egrets, and shorebirds."

Within minutes, he was sure that he was looking at the footprint of a small shorebird, similar in size to a modern-day snowy egret or tricolored heron, both of which leave distinctive four-toed footprints. His findings appear in the current issue of "Palaeontology."

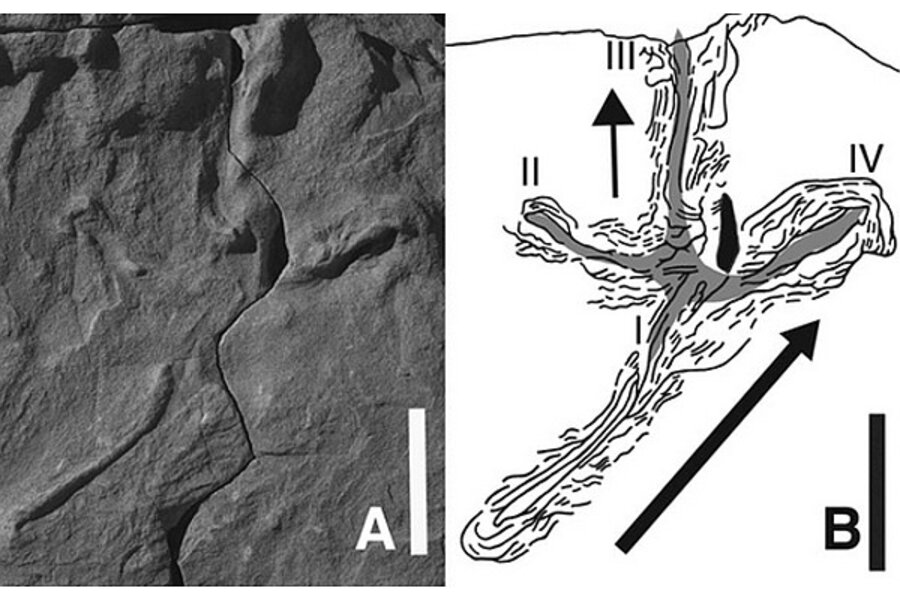

While not all Cretaceous-era birds had a "hallux," a backward-facing fourth toe, and in fact some theropod (bird-like) dinosaurs did, four slender toes splayed out like an off-kilter peace sign nearly always means bird, says Dr. Martin. Tyrannosaurus rex, for example, had a vestigial rear toe up near his Achilles tendon, but an elevated toe wouldn't show up in a footprint, he notes. "In bird feet with that fourth toe, the hallux was down on the ground with the tracks, where that same toe on non-avian theropod dinosaurs was usually raised."

What's more, this hallux had left a long groove behind it, which Martin's thousands of hours watching birds make tracks along the Georgia shoreline told him was the sign of a bird coming in for a landing.

"The then-soft, wet sand had been sliced by the sharp claw on the hallux, which contacted the sand first before the rest of the foot registered. As this toe slid forward and stopped, the other digits came down, and forward momentum caused their leading edges to push against the sand, mounding it in front of these toes," he writes.

The footprint in question appeared on a slab of sandstone with two other footprints. They were all about the same size, but only two of the three showed signs of a hallux, leading Martin and his colleagues to conclude that two birds and a bird-sized dinosaur had made the three prints. Because wet sand dries quickly, the three footprints must have been made within a narrow window of time, possibly within the same day, says Martin. The dinosaur and the birds must have shared an ecosystem, just as modern animals might share a watering hole or visit the same stream.

The rock containing the footprints was found on November 29, 2010, by Sean Wright and Alan Tait, two volunteers from the Museum Victoria in Melbourne, Australia. They were scouting the shore for more of the dinosaur bones that gave Dinosaur Cove its name when they found what looked like dinosaur footprints. Four months later, Mr. Tait went back to the site, broke the slab into four backpack-friendly pieces, and schlepped the 100 pounds of sandstone back to civilization.

When the footprints were made, about 105 million years ago, Australia was much farther south than it is now. Dinosaur Cove, which is now near the southeastern tip of Australia, was then in a temperate region close to the South Pole. Birds and non-avian dinosaurs were still in the process of separating on their evolutionary journey. Many scientists now class birds as theropods – the class of dinosaurs that includes T. rex and velociraptors – and they're searching for clues into how modern birds diverged from their giant cousins, and how feathered flight evolved.

These footprints provide important clues toward those questions, especially if Martin is right that the long groove is evidence of flight, and not just hopping or foot-dragging.

"Could we all be wrong, and none of these tracks are from birds, but from some theropod dinosaurs that were very close to birds in their foot anatomy?" Martin asks. "Sure, that’s possible, but not likely at this point. Could I be wrong about taking one track and interpreting it as evidence of flight? Again, that’s possible. Alternate explanations include that the bird just hopped – perhaps with a flap or two – before landing. Or its foot just slipped on the wet sand as it was walking forward. However, in my experience with modern birds, such tracks are even more rare than volichnia (flight traces). Could Cretaceous birds in polar Australia have been more clumsy than those today, hence their slipping tracks would have been more common? OK, now that’s just silly. Let’s just celebrate this find for what it is."