Ancient mammal beat the dinosaurs, was outdone by rodents

Loading...

Some 66 million years ago, an entire ecosystem – one packed with the largest animals that ever lived – was torn from the planet in a catastrophic event often pinned on a rogue meteor. But not everything died. The non-avian dinosaurs were gone, but ancient crocodiles soldiered on. So did some birds and some fish.

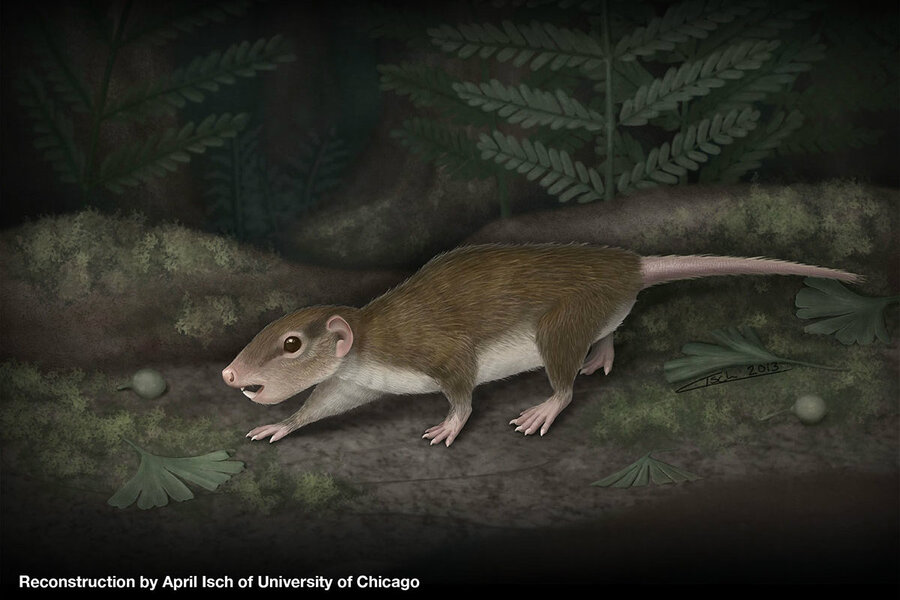

And so too did some of the meekest-looking of that ancient ecosystem’s animals: the multituberculates, a lineage of small, ratlike mammals that originated some 170 million years ago and lasted for about 135 million years, before finally succumbing to natural selection’s pruning shears.

Scientists have now recovered the oldest complete skeleton ever found from that lineage, a 160-million-year-old fossil called Rugosodon eurasiaticus. Found in Liaoning province, in northeastern China, Rugosodon is a telling data point in scientists’ effort to plumb the stops and starts – the roots and tree tips and dead-end buds in-between – in the mammalian evolutionary tree, which tops out with the three modern mammal lineages familiar to us.

In that complex tree, there are big questions: Where did the features we associate with modern mammals first evolve? What foreign-looking attributes and behaviors appeared in the animals that were pruned from that tree? Why did multituberculates make it through the mass extinction event but not to the modern age?

Rugosodon does not deliver a solid answer to those questions, but its discovery does begin to pull back some of the thick branch-work to let scientists peer into the mammalian tree, says Zhe-Xi Luo, a professor of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago and an author on the paper, published in Science.

Rugosodon, a petite, rodent-like animal, has several features that turn up in modern mammals. Most notable among them are its flexible, 180-degree-turning ankles, the earliest known examples of the hyper-mobile ankle. That means that the anklebones found in some modern marsupials, including opossums, existed at least 160 million years ago.

And that anklebone, a universal feature in all multituberculates, might also be a clue as to how these ancient mammals managed to proliferate around the ancient world to such numbers that the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period could not obliterate all of them. Perhaps, that versatile anklebone was an adaptive feature, one that was re-purposed again and again to support whatever niche the multituberculates were called upon to fill, Luo said.

“Multituberculates were very, very successful, says Dr. Luo. “When the big, clunky dinosaurs got wiped out, multituberculates managed to hang on.”

But the multituberculates did not survive everything: the lineage went extinct around 35 million years ago, just about the time that the modern rodent’s lineage emerged. It’s possible that rodents, who are better breeders than multituberculates, could have out-competed the more ancient mammals, Luo said. “It’s a very puzzling case.”

The paper follows a recent paper in Nature that Luo also co-authored, describing a pre-mammal, Megaconus. That 165-million-years-old precursor to modern mammals suggested that mammal characteristics, such as fur, well predate the existence of actual mammals.