Tibet shepherds live on climate frontier

Loading...

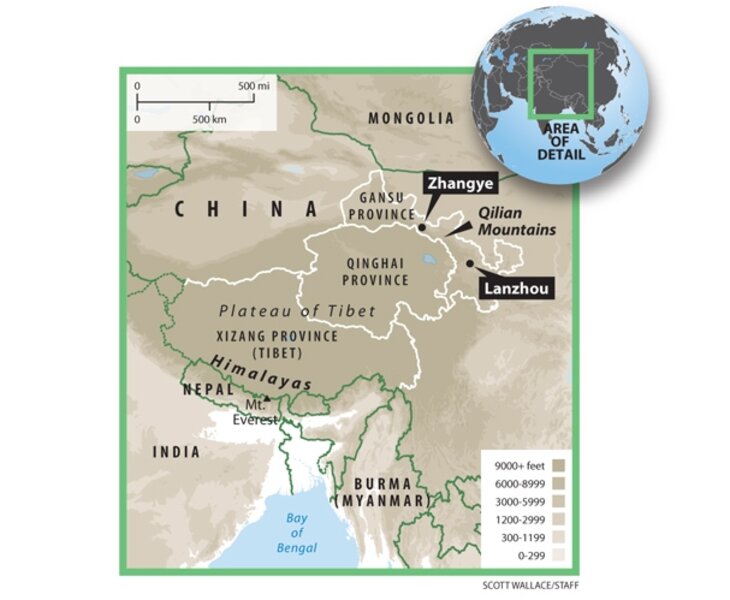

| Lanzhou, China

For Tenzin Dorje, the road home keeps getting longer. Each year the Tibetan shepherd must walk farther to find streams where his sheep can drink.

“I am an old man,” he says, clutching the neck of his cane. Sometimes he trudges six hours a day, twice his old route. He has contemplated learning to ride a motorbike like his grandson, but fears it might be too discomfiting for an 80-year-old man.

The problem is that streams in the province of western China where he lives are drying up, receding into the mountains.

As recent years have brought higher temperatures and altered how snowmelt trickles down from glaciers on the Tibetan-Qinghai plateau, water is becoming scarce.

Mr. Tenzin lives in a small village nestled amid dramatic mountains peaks. Strings of Tibetan prayer flags flap against a still-brilliant blue sky. Yet this apparent purity and timelessness masks another reality: He is living on the frontier of climate change.

Tenzin’s village is on the slopes of the rugged Qilian mountains in western Gansu province. Glaciers on the mountains are the primary source of water for humans, farms, and industry in his village of Baijiaowan and for others north and south of the range.

The streams distinguish the landscape, including a string of oasis towns along the Old Silk Road, from the abutting Gobi Desert. Today, the desert is expanding.

“The climate is changing,” says Zhang Mingquan, a professor of earth and environmental sciences at Lanzhou University, in the provincial capital. “Snow is the source of the stream water, and now the stream water is less than before.”

Recent years have seen higher temperatures and less precipitation. As a result, mountaintop ice is receding.

The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences estimates that the glacial area on the Tibetan-Qinghai plateau, the world’s largest ice sheets outside the poles, is shrinking about 7 percent each year.

It might seem that melting glaciers would bring more water in the short term. But that isn’t necessarily the case, says Michael MacCracken of the Climate Institute in Washington.

“Glaciers and snow on mountains serve as a storage mechanism for water, holding it for later,” he says. “The area of the glaciers is an indication for how well that system is working.” Think of glaciers as a

bowl, and snowfall as rice – a shrinking bowl holds less rice. Receding glaciers capture less annual snowfall.

“Without the glaciers, snow and rainfall tend to seep into the soil – usually mountain soil is quite porous – and then it later evaporates,” says Dr. MacCracken.

In nearby Minqing county, instead of walking farther for water, farmers dig deeper. Fifty years ago, wells tapped groundwater at 50 feet. Now they must drill 100 feet or more. With less snowmelt, groundwater is not fully replenished.

Glaciers stretching across the towering Tibetan-Qinghai plateau sustain all the great rivers of Asia – the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers in China; the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra in India; the Mekong and Salween in Southeast Asia.

“With climate change, all these rivers will have greatly reduced flows,” says Carter Brandon, director of the World Bank’s China environment program in Beijing. “There will also be much more seasonal variation – when flow is more dependent on rainfall, as opposed to the steady inflow of snowmelt from glaciers.”

The glacier system delivers water to more than 300 million people in China – and 1 billion across south Asia.

The region is among the globe’s most rapidly warming. Average annual temperatures on the “rooftop of the world” have climbed 2 degrees F. in two decades.

Chinese scientists expect the total area of the glaciers to halve every 10 years. By 2100, they predict, the glaciers may have largely vanished.

Those hit first and hardest by climate change, like Tenzin Dorje, tend to live in poor communities on the margins, on mountaintops or by the sea. Typically they have contributed little to global carbon emissions.

There is now a new push to address their concerns. In 2007, the Rockefeller Foundation established a five-year, $70 million “climate-change resilience initiative” to assist developing countries. In December 2007, during climate talks in Bali, Indonesia, United Nations negotiators drafted a framework for a new “adaptation fund” to aid poor countries and communities.

The critical issue of what practical measures can be taken remains. A team of scientists in Switzerland has begun to research the possibility of shielding glaciers from rising summer temperatures with blankets of insulating foam. But such investigations are only preliminary.

Other research on addressing global water shortages includes promising (if costly) ways to desalinize seawater and recycle wastewater. But such approaches will work better in coastal areas and cities, not landlocked villages like this.

Research into solutions is attracting more attention from scientists and policymakers today. “Now we’re beginning to focus more seriously on these issues,” says MacCracken, the climate scientist.

“I used to think adaptation subtracted from our efforts on prevention,” former vice president Al Gore recently told the Economist magazine. “But I’ve changed my mind. Poor countries are vulnerable and need our help.”

But who will foot the bill? According to the UN, by 2015 approximately $86 billion annually will be needed for adaptation efforts.

The small home of Zahxi Rangou is perched on a mountainside overlooking a snowy valley and a white pagoda temple. He is one of 15 lamas residing on the grounds of the Tibetan Midi Temple, tucked in the Qilian mountains in Gansu province. The young monk has two rooms: One is warmed by a stove for visitors. One is cold and full of books and a computer.

Here he spends his days in prayer and study. He has Internet access, and is well-read on climate science.

“The glacier is depleting,” he says matter-of-factly. “It’s melting in the summer. And the weather is getting drier.” His knowledge is power, but there are limits on how he can use that power. Tibetans, an ethnic minority in China, are closely watched by the government. It is difficult for leaders of his community to organize around environmental or other issues in China.

He says he doesn’t use e-mail, because it can so easily be monitored. Many Internet news sites are blocked.

At nearby Zhuanlong Temple, no one answers a knock at the door. The lama there has left on a special mission this winter: He will spend two weeks praying at the source of each stream for its bountiful return.