U.S. scraps ambitious clean-coal power plant

Loading...

Prospects for nearly emissions-free coal power in the United States have dimmed in the wake of the US Department of Energy's decision to pull the plug on a "clean coal" demonstration plant called FutureGen, observers say.

Instead of the $1.76 billion project, which was expected to capture and store underground 90 percent of its greenhouse-gas emissions, the Energy Department is budgeting $241 million for several commercial power-plant projects that will capture and store a smaller share of their emissions. Federal officials called it a money-saving move.

"This restructured FutureGen approach is an all-around better investment for Americans," Samuel W. Bodman, secretary of Energy, said in a statement. The smaller projects will still show that at least 1 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions can be captured annually for underground storage, he added.

While the new projects will together sequester more carbon emissions than FutureGen by itself, and could be valuable demonstrations in a commercial setting, some observers questioned the wisdom of backing off FutureGen just as it was about to get going.

"This is a backward step for clean-coal technologies, very unfortunate," wrote Steve Jenkins, vice president for gasification services at CH2M Hill, one of the nation's leading power engineering firms based in Denver in an e-mail responding to the decision.

The high-concept power plant appeared on the verge of becoming a reality December when the FutureGen Alliance, a business consortium, announced it would locate the project in Matoon, Ill.

Under the deal, 13 partners – including China, Australia, Britain, and Germany – would have paid 26 percent of the cost with the DOE paying 74 percent. A key part of FuturGen was the potential environmental impact, some environmentalists say because China's coal-fired power plants are among the largest emitters of greenhouse gases.

"A lot of environmentalists never really thought FutureGen was serious," says John Thompson, director of the Coal Transition Project for the Clean Air Task Force, an environmental group headquartered in Boston. "It shouldn't be an either-or question. We need both."

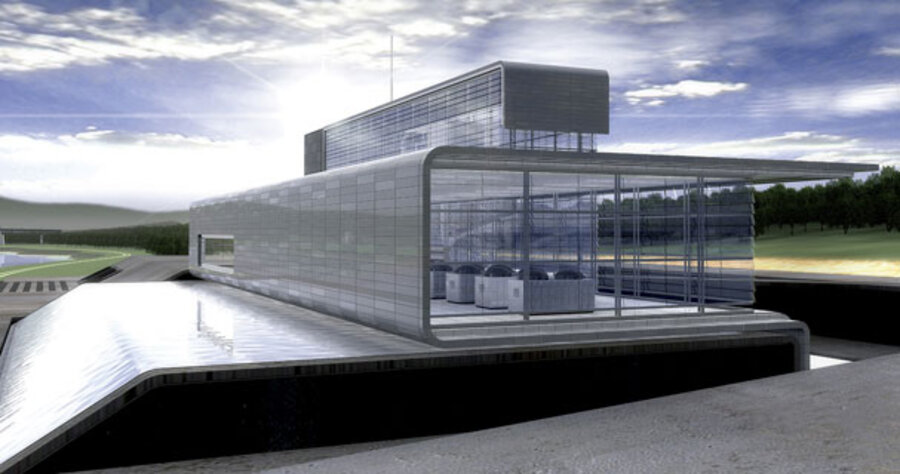

The result, he says, is to give ammunition to those who said the White House was just using FutureGen to show it is being active on stemming global warming – without doing too much more than a few engineering studies and an artist's rendering of a futuristic-looking coal-fired power plant.

"Retreating from FutureGen now just ends up making carbon storage as a whole seem less possible," Mr. Thompson says. "This was a project that only the feds could do."