Into the twilight zone: An age of discovery unfolds beneath the waves

Loading...

| Monterey Bay, Calif.

Some 20 miles off the Monterey Bay coast, Kelly Benoit-Bird lights up as a delicate, pink creature drifts onto the screen in front of her. After asking the drone pilot to zoom in for a closer look, she calls out, “A cockeyed squid! I’ve never seen one before.”

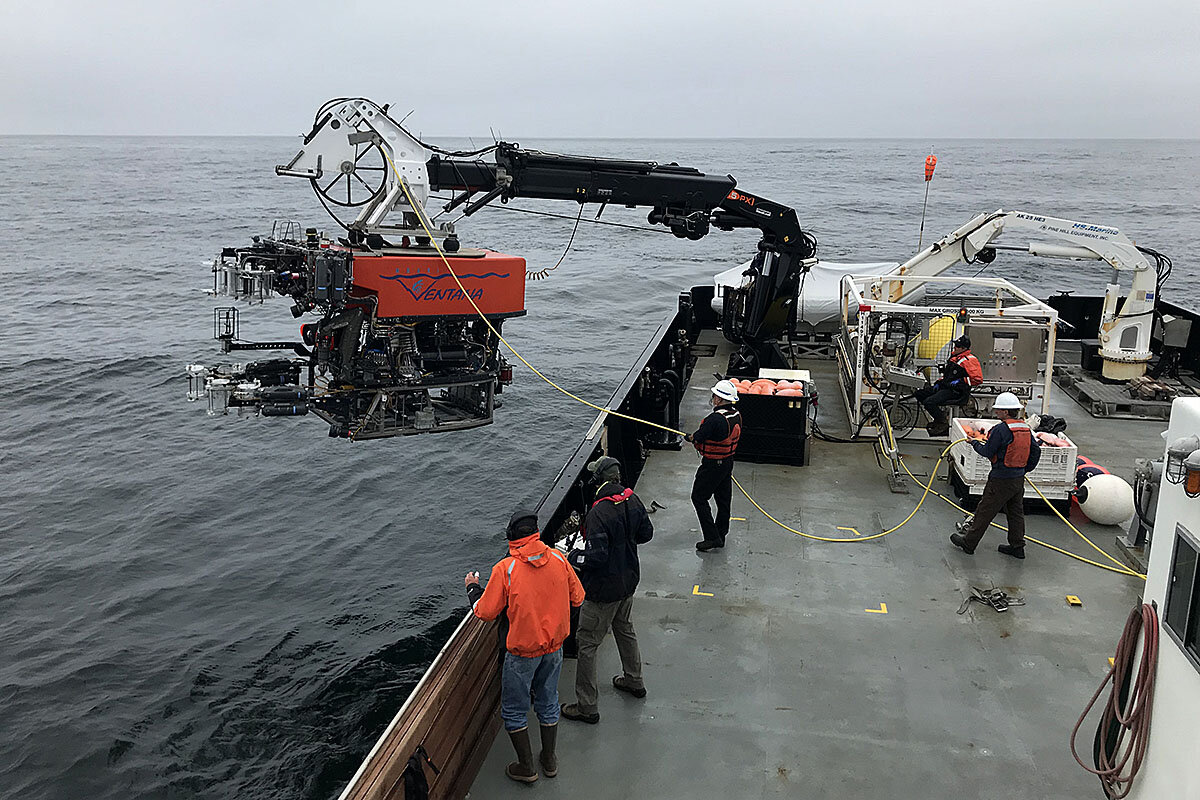

Dr. Benoit-Bird is on board the Rachel Carson, watching intently as live video streams in from the Ventana, a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) descending through the “twilight zone” of waters deep below the ship.

The robotic envoy’s mission: to glean insights into the twice daily swell of tiny critters traveling up and down the water column – likely the largest migration on Earth. The excursion is another data collection point in a long-running experiment to monitor these waters and to better understand the mysteries that lie beneath the surface of the sea.

The ocean covers more than 70% of the planet’s surface, constitutes 95% of its living space, contains 97% of its water, and is critical to life on Earth in myriad ways: as a source of food and oxygen, and as a driver of our climate.

But for most people, the ocean is a world almost as alien as the moon, a smooth surface that makes a pleasing backdrop to a sunset or a fun playground for kids on the beach. As scientists’ understanding of this world evolves – from shallow coral reefs to the depths beyond sunlight, from the complex living ecosystem to the ocean’s importance as a carbon sink and a climate regulator – so too are people’s perceptions of this unfamiliar world.

“The ocean is the most important thing you rarely think about,” says Janis Searles Jones, CEO of the Ocean Conservancy, an advocacy group. “You need a healthy ocean to have a habitable planet.”

An age of discovery

Getting people to care about that ecosystem has at times been an uphill battle, she says, but new research and scientific exploration have helped more people understand just how dynamic and varied an ecosystem the ocean is, and how vital it is to life on Earth, both for people who live near the ocean and for people who live thousands of miles away.

“The coolest thing about the ocean is you can still find new creatures you’ve never heard of or seen before,” she says. “Deep-sea creatures are beyond your wildest imagination, the stuff of science fiction or cartoons or dreams.”

For the scientists engaged in unraveling those mysteries, this is still an age of discovery. New technology is enabling them to look deeper and farther and to understand places and interactions that until recently were entirely unknown.

The equipment aboard the Rachel Carson and at today’s dive site is a testament to that technological progress. In addition to the remotely operated Ventana, autonomous underwater vehicles travel untethered, programmed to take measurements and collect video and water samples. An undersea cable on the seafloor nearly 3,000 feet below the surface powers acoustic sensors, tracking both ocean sounds and movement of organisms in the water above it.

As the ship heads to the dive site, Samuel Urmy, a postdoctoral fellow at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, points out the acoustic data, updating in real time, that shows how the mass of tiny creatures migrates between the mid-ocean and the upper ocean every morning and evening – equivalent, for them, to completing a 10K race twice a day.

Despite the wealth of data now available, these scientists are the first to say they’re just starting to scratch the surface of understanding the complex web of interactions between predators and prey in this mid-water zone.

“This is hugely unknown, so it’s exciting,” says Dr. Urmy.

And the more scientists learn, the clearer it becomes that the ocean, while incredibly resilient, is facing massive threats: from climate change and plastic pollution to overfishing and drilling for oil and gas.

The vast unknown

For many years, the deep-sea floor was once thought to be a largely barren environment. But in recent decades researchers have discovered thriving – and highly varied – habitats rich with biodiversity, says Lisa Levin, an oceanographer with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who has been studying the deep sea for almost four decades.

The ecosystems of the deep sea can be as different from each other as forests and grasslands and deserts are on land, Dr. Levin says. Scientists are just beginning to understand the “superpowers” that enable animals to survive in these extreme conditions: withstanding the hottest water, the lowest oxygen, the highest pressure.

“But at the same time that we’ve discovered all this biodiversity, we have begun to look to the deep ocean for resources,” says Dr. Levin. “Sometimes we’re destroying things before we even begin to discover them.”

What becomes increasingly clear with each discovery is just how much we still have to learn.

“The more we measure, the more we find things that – wow, we didn’t know the ocean worked that way,” says Mark Abbott, president and director of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

On the Rachel Carson, there is a palpable sense of excitement when the Ventana gets lowered into the water and the dive begins. The scientists may not be down in the ocean depths themselves, but immersed in the images in the ROV control room – and directing the ROV pilot to shift the view, or collect water samples, as Pink Floyd and Tom Petty play softly in the background – it feels as if they’re down there, too.

“Without the ocean, we’d already be toast”

Dr. Benoit-Bird, an expert on using acoustics to understand animal behavior in the mesopelagic zone and the director of this dive, characterizes these dives as “hours of boredom punctuated by moments of intense excitement.” On this dive, she loved seeing the cockeyed squid, and she’s struck by the diversity of species seen: jellyfish and shrimp, tiny anchovies and hake, copepods and pteropods, and giant larvacean houses.

The mesopelagic region – the ocean’s middle zone, or twilight zone – is hugely unexplored, says Dr. Benoit-Bird. “But these animals are an active conveyor belt moving hundreds of meters each night, moving all this carbon,” she adds, noting that the estimated biomass of the mesopelagic is now being revised, and may be 10 or even 100 times greater than was previously thought.

Dr. Levin says that thrill of discovery and sense of wonder continue to motivate her as well. Humans have seen only about 5% of the seafloor, she notes. “Every time we look at new places, we discover new things.”

In January, Dr. Levin was on a research cruise off the coast of Costa Rica when she discovered that fish lay their eggs in xenophyophores – fist-sized single-celled creatures that have long fascinated her. “For a long time I’ve studied [these giant protozoa] as little hotspots of biodiversity,” says Dr. Levin, her voice lighting up with the joy of discovery. “But having a fish use a single-celled organism as a nursery habitat is pretty amazing. ... It’s a small discovery, but it’s not an insignificant thing.”

When people ask her why the ocean and deep sea matter, Dr. Levin says she points to the climate system – “without the ocean we’d already be toast” – and the incredible biodiversity that hold pharmaceutical and bioinspiration potential: sea corals that are a template for bone implants, sponges with superconductor powers, microbes that absorb carbon dioxide.

“There’s an endless array and we’ve just scratched the surface,” says Dr. Levin. “There are also functions and services [the ocean provides] that we haven’t even discovered yet, that we don’t know that are important. And some people believe it’s just our responsibility to take care of life on the planet.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct Janis Searle Jones's title at the Ocean Conservancy. She is the CEO.