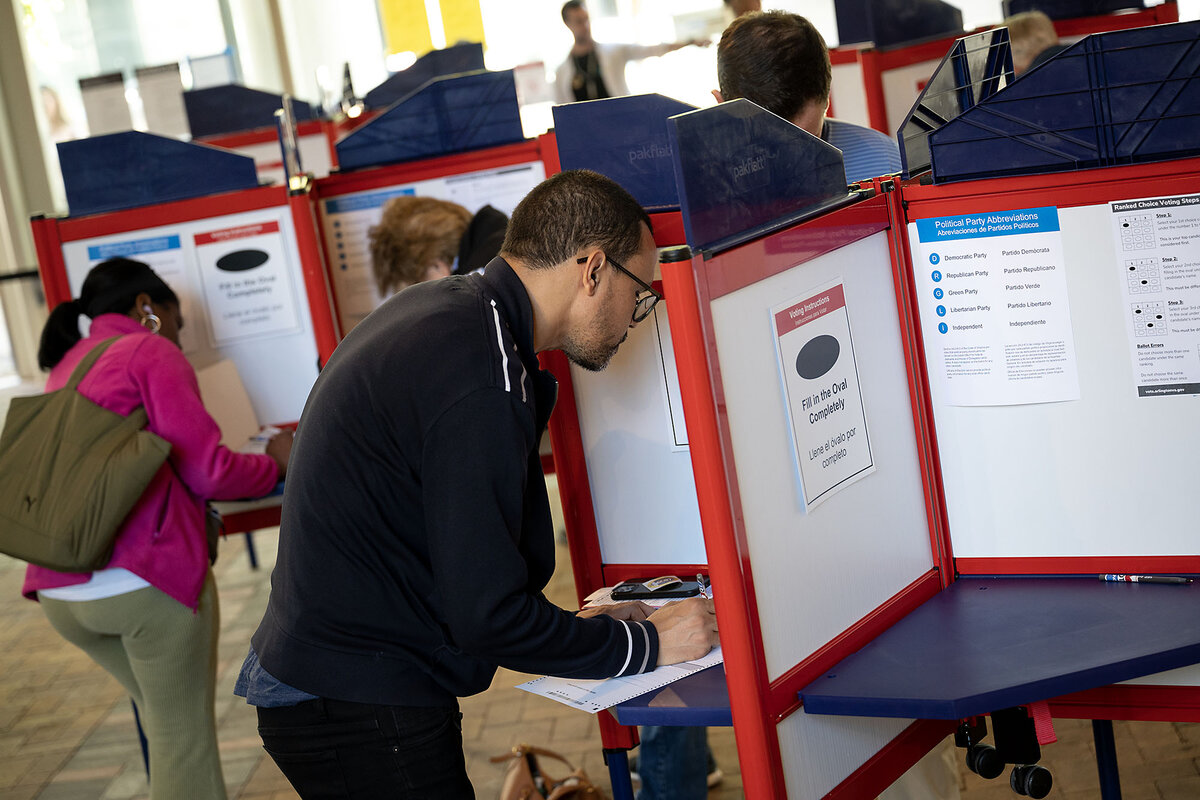

Election Day marks the end of a tense presidential campaign season of high drama and record-high spending. Voters across the United States largely agree on the problems, but are split on who offers the best solutions.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today, our live updates blog (which you can read here) will keep you up to speed on all the important developments of Election Day. With such a cascade of news, we wanted to make sure you had a place to go for news you could trust.

As I think about this moment, I decided to take a step back and look at how, some 230 years ago, one of the American founders was considering deeply the question facing American voters today – and what that means for the road ahead. You can read the column here.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Netanyahu fires defense minister: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has dismissed popular defense minister, Yoav Gallant, in a surprise announcement. Mr. Netanyahu and Mr. Gallant have repeatedly been at odds throughout the war in Gaza.

• Ukraine war: Ukraine’s defense minister says Ukrainian troops have engaged for the first time with North Korean units that were recently deployed to help Russia.

• Boeing strike ends: A strike by 33,000 Boeing factory workers concludes after more than seven weeks. Unionized machinists voted Nov. 4 to accept a company contract offer that includes a 38% wage increase over four years.

• Nigerian death penalty: Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu has ordered the release of 29 minors facing the death penalty after being arraigned for allegedly participating in protests against the country’s worst cost-of-living crisis in a generation.

• Redistricting case: The U.S. Supreme Court is taking up a new redistricting case involving Louisiana’s congressional map with two mostly Black districts.

( 5 min. read )

All U.S. presidential elections are consequential, but this year’s race stands out for its particularly momentous events, occurring in quick succession. The results will be historic, too.

( 6 min. read )

Amid falling trust in the electoral process, we look at the chain of custody for a ballot in the state that was ground zero for Republican attacks on mail-in voting in 2020: Pennsylvania.

( 9 min. read )

A major step in moving the dial on postsecondary career and technical education comes during a nationwide push to bolster middle-skill labor, and get Americans to work.

Profiles in Leadership

( 5 min. read )

Muhammad Auwal Ahmad’s app is meeting displaced young people where they are – and helping opportunities flow to them.

In Pictures

( 2 min. read )

Restoration work can leave a city feeling like a preserved tourist attraction. But Nelson, British Columbia, is a living, breathing place with an evolving history.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

A nation polarized by politics is having a clarifying moment. A week after an intense storm battered its eastern coast, Spain has seen thousands of volunteers come from all directions to help towns devastated by floods. Many traveled miles by bicycle or on foot.

“Humanity is still capable of forgetting its differences,” said Toni Zamorano, who spent hours on the roof of his submerged car in the town of Sedaví. “Here, race or economic level don’t matter. This solidarity makes you feel great,” he told The New York Times.

Political differences in Spain bore little relation to the unity felt by ordinary citizens during the disaster. That may be because most Spanish citizens rally around priorities such as dealing with the effects of climate change, according to Miriam Gonzalez and Begoña Lucena, founders of España Mejor, a civil society group. “Polarization is a major distraction,” they stated in the European Business Review last year.

The storm’s impact brought a visit by King Felipe VI on Sunday to the city of Paiporta, where floods had swept away thousands of homes and businesses. Some residents pelted him and his entourage with mud and insults out of anger over the government’s slow response to the disaster.

In an address a few days earlier, the king spoke of the need to build coherent societies based on dialogue and concern for the common good. “It is ... the obligation of institutions, but also [of citizens], to fight against everything that separates, even one iota, from that integral respect that we owe to the person, to any person, to the dignity of any human being,” he said.

In Paiporta, the king showed what that can look like in practice. His security detail begged him three times to leave the throng. He and Queen Letizia stayed. They listened, hugged, and wept with residents. Anger softened. In a poll published Tuesday in the online newspaper El Español, the townspeople expressed their gratitude for the monarchs’ visit. They acknowledged the risk they had taken to be there. Back in Madrid, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón said his government should have done more sooner.

Spain’s unity at this moment is from the bottom up. Or, as Spanish professional soccer player Ferran Torres wrote on social media, “The people are the ones who save the people. ... Long live Spain.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 1 min. read )

In God, this poem conveys, there are no winners and losers – we’re all divinely equipped with the innate grace, strength, and goodness we need to thrive.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thank you for checking in with the Monitor today. Please keep visiting our live updates blog at CSMonitor.com for the latest news. And if you have any thoughts on the blog, please let me know at editor@csmonitor.com.