Intel is coming. Ohio community colleges say the state’s workers will be ready.

Loading...

| Columbus, Ohio

On a 1,000-acre plot of land in New Albany, Ohio, 15 miles northeast of Columbus, dozens of cranes tower in the sky, their jibs and booms moving while hooks swing back and forth. They are building, and their work will beget more work for many years to come. Intel is coming.

The semiconductor behemoth based in Silicon Valley is building two chip manufacturing plants at a cost of $20 billion. The company estimates they will bring 3,000 new jobs to this Rust Belt state.

“Ohio is benefiting from reshoring that’s happening in the U.S., and [with] the investment that’s happening at a federal level as well as the state level, there’s no doubt about it,” says Scot McLemore, executive-in-residence at Columbus State Community College.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA major step in moving the dial on postsecondary career and technical education comes during a nationwide push to bolster middle-skill labor, and get Americans to work.

Like an NFL general manager, Intel has cast a wide net to recruit talent to fuel its workforce. CSCC is one of several community colleges that Intel has partnered with in Ohio to build curriculum. The company donated $50 million to these schools and other education initiatives across the state.

“We are becoming more focused on that talent demand, and we’re identifying barriers that are preventing us from getting more individuals in our communities into those pathways,” Mr. McLemore adds.

Columbus is the fastest-growing city in the state, and Intel is one of several Fortune 500 companies that have made major investments in the surrounding area. To prepare for its arrival, Intel wants to be sure that it has workers ready to go when the new campus opens in 2027 or 2028. In partnerships like the one with CSCC, the company has shared information on its chipmaking process with schools and designed curriculum to ready students for entry-level positions that require anything from a certificate of completion to an associate degree or higher.

This is a major step in moving the dial on postsecondary career and technical education, or CTE. It comes during a nationwide push to bolster middle-skill labor, and get Americans to work. It also coincides with companies dropping degree requirements for certain positions, and more Americans being skeptical about the high cost of a college degree.

“They want to revitalize Ohio back to the manufacturing hub that it once was,” says Mark Mahoney, assistant dean of the engineering technologies department at CSCC. Dr. Mahoney says that a big company like Intel coming to the area brings attention, and that attention will bring other companies. That’s already happening in Ohio.

Honda, which has had plants near Columbus going back to the early 1980s, announced a $700 million investment to retool them for production of electric vehicles. Additionally, the car company announced a $3.5 billion investment/partnership with LG Energy Solution to produce the batteries to power them, via a new plant in Fayette County, 40 miles southwest of Columbus. Biotech and pharmaceutical companies also are opening offices in the Columbus area.

“The whole fabric of society rests upon labor”

To capture the ethos of the area, look no farther than Front Street, near the entrance of the 14-story-tall Ohio Supreme Court building. The marble building has an inscription guarded by two female lions that reads, “The whole fabric of society rests upon labor.”

The state legislature in Ohio has invested millions in postsecondary CTE, such as the program at CSCC. These programs can be in the form of boot camps and one-time certificate-level accreditation for employees to get their foot in the door, or degree programs at community colleges. This helps fulfill the middle-skill jobs that President Joe Biden has repeatedly touted. Bolstering the economy with skilled workers has been a bipartisan theme. This comes as colleges are facing an expected enrollment cliff: Over the next 10 years, 15% fewer college-aged students are projected to enroll in universities.

Skylar Eastman and Addison Swartz are among those looking for a different path. When the high schoolers emerge from lockers in the welding lab at the Delaware Area Career Center, they already look like professionals. They wear fire-resistant jackets; helmets with auto darkening to protect against ultraviolet and infrared rays, as well as flying sparks; and welding caps to protect their hair. To add flair, Addison shows off inch-long pink-and-white nails that she designed herself.

The only two girls in the welding program are standouts, chosen as ambassadors for their community college and already capable of crafting metal chairs and barbecue smokers. Both of them want to get straight to work.

“My parents have the money for me to go to college, but one thing that I looked at was if I’m going into welding and I’m guaranteed a job, and I’m guaranteed to be working for the rest of my life,” Skylar says. She will be moving to Nashville, Tennessee, after graduation to work with her aunt and uncle at their welding business.

Addison is also sold on welding.

“I wouldn’t want to spend thousands of dollars and put myself or my family in debt,” she says. Neither of her parents attended college, and she says that they built good lives for themselves. Addison feels as if she got a leg up by learning a trade in high school. She and Skylar are set to graduate with three different welding certificates and one for operating a forklift.

“If you have the opportunity to go to a trade school for high school, it’s definitely a lot cheaper for people and it’s a way better experience because you’re able to go out into the field and make that money back,” Addison says.

Building an Intel curriculum

The Intel model for CSCC came with a $2.8 million grant to build out curricula for instructors to share with other community colleges. Industry experts from Intel saw what CSCC taught in its engineering technology program and added specifics to introduce students to life at Intel. Intel subject matter experts and faculty created new classes – manufacturing fundamentals, semiconductor fabrication, and vacuum systems technology. Students can get certificates in one year of study or associate degrees in two. They also have the opportunity to scale up later, which can lead to higher earning potential.

“It’s just not Intel coming along. Manufacturing is a multifaceted system, so when a big company comes, they are going to have to have support companies. They might not be as popular or well known, but these companies will basically work on the equipment that Intel uses, and that company will have a company that supports them, and it ends up being a domino effect,” Dr. Mahoney says.

That domino effect could go on to fill the 7,000 job vacancies in the manufacturing sector in Ohio that were listed as recently as 2020. The money invested is impressive. Under the CHIPS and Science Act, which Congress passed in 2022 to increase domestic production of semiconductor chips, the U.S. Department of Commerce gave $8.5 billion to Intel in direct funding and another $11 billion in loans. Ohio is getting its share of the investment, as are plants in Arizona. Other U.S. companies are building plants in Utah and Texas.

Can CTE shake its past stigma?

CTE started off as a vehicle to catapult people into the middle class more than a century ago, when it was still called vocational education. In 1917, Congress passed the Smith-Hughes Act to plug workforce labor gaps and amplify precollege education in agriculture and trades.

In the past, vocational education had a legacy of racism and classism, shuffling students of color and disadvantaged students into low-quality programs with little earning potential. Students who went to trade school had little chance for upward mobility, says Jeff Strohl, director of Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, citing past research.

Dr. Strohl believes that changing attitudes about the return on investment of four-year colleges could be a moment for CTE to thrive. However, he adds, more money needs to be invested to be competitive with other countries like Germany, whose dual system includes intensive secondary vocational education and apprenticeships. He adds that postsecondary CTE education needs to be trumpeted so job seekers can get some skills and education in degree-based programs, which push earnings higher. And while plumbing and other trades have led to recent headlines about millionaires wearing tool belts, he says it’s dishonest to push the notion that every middle-skill job will pay six figures.

Nor is CTE without criticism, with experts concerned that students could be pigeonholed in one trade, without the ability to pivot if the labor market shifts.

“My basic concern is that CTE might substitute for solid basic skills and might not give students the ability to adapt when the demands of the labor market change,” writes Eric Hanushek, an economist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University who has written extensively about the economics of education, in an email.

Dr. Hanushek says that the lack of adaptability was a key finding in a study he wrote that compared employees who had finished apprenticeship programs in 11 countries. It showed that while they started off with better job prospects than people with general education, over time their pay did not increase as high and they found themselves out of work after skill requirements changed.

“This lack of adaptability was the key finding,” Dr. Hanushek adds.

“Remember those positions? ... They’re ready.”

A month into fall semester at CSCC, the college held its annual Major Fest, when undeclared students learn about potential programs. The engineering and technology program placed a table in the center of campus, near where students played cornhole and ate snacks.

Christa Wagner stopped by to chat. She took the semiconductor fabrication class last year and is considering taking the other two.

“With the opportunity that Intel presents, I did want to add those courses onto my regular degree so that I will have those skills available,” Ms. Wagner says. She enrolled at CSCC after working 20 years in customer service and hopes the new skills she’s learned will lead to better-paying work. She is set to graduate before the Intel plants will be complete.

“I want to go out and get some experience in my major now, but when that opportunity becomes available, I would be able to transition into that,” Ms. Wagner says hopefully.

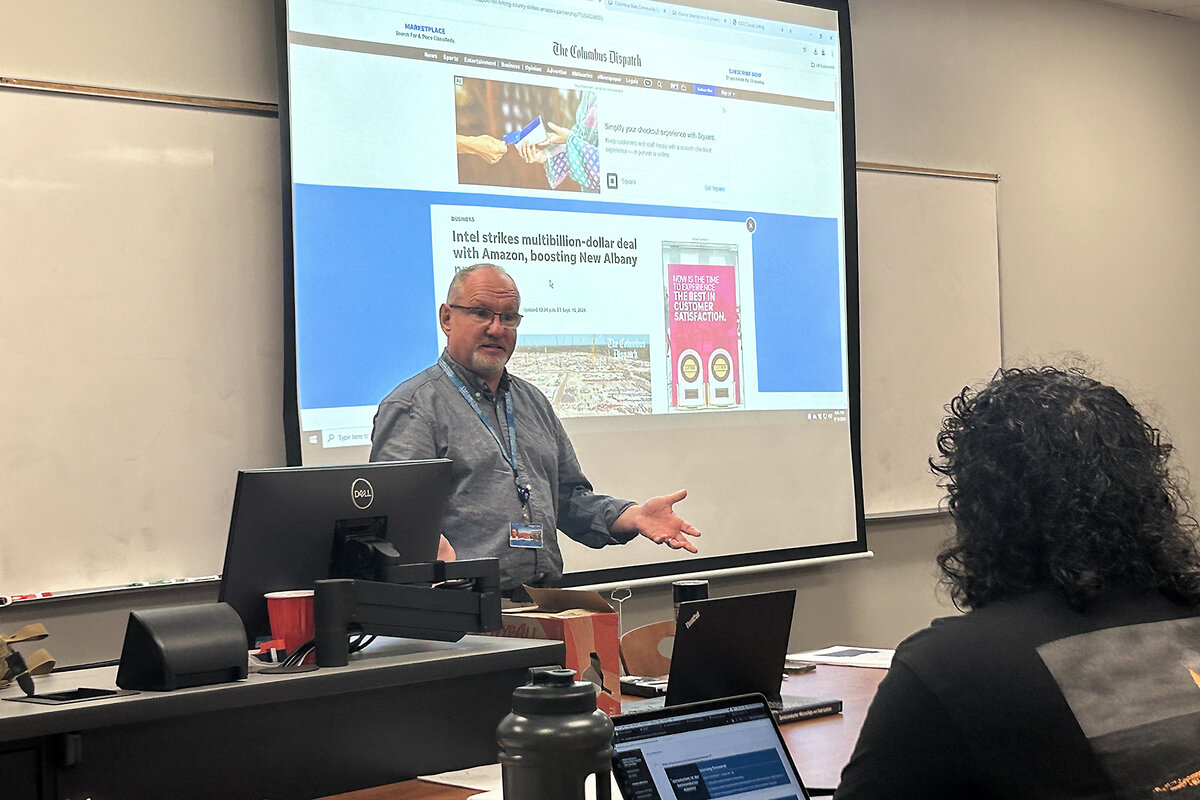

That hope is spreading. Since the Intel program revamp, enrollment in the engineering program has risen 20% per semester. Students and administrators at CSCC grew worried that Intel would pull out of the Ohio deal and sell the plants to another company after construction was delayed. But at Chris Dennis’ evening semiconductor class on a recent night, everyone was all smiles. He shared a newspaper headline about a multibillion-dollar partnership between Intel and Amazon to design chips for Amazon’s central Ohio data center. He also shared an update about Intel internships that caught students’ attention.

“Remember those positions that we’ve been talking about in Arizona?” he asks. “They’re ready.”

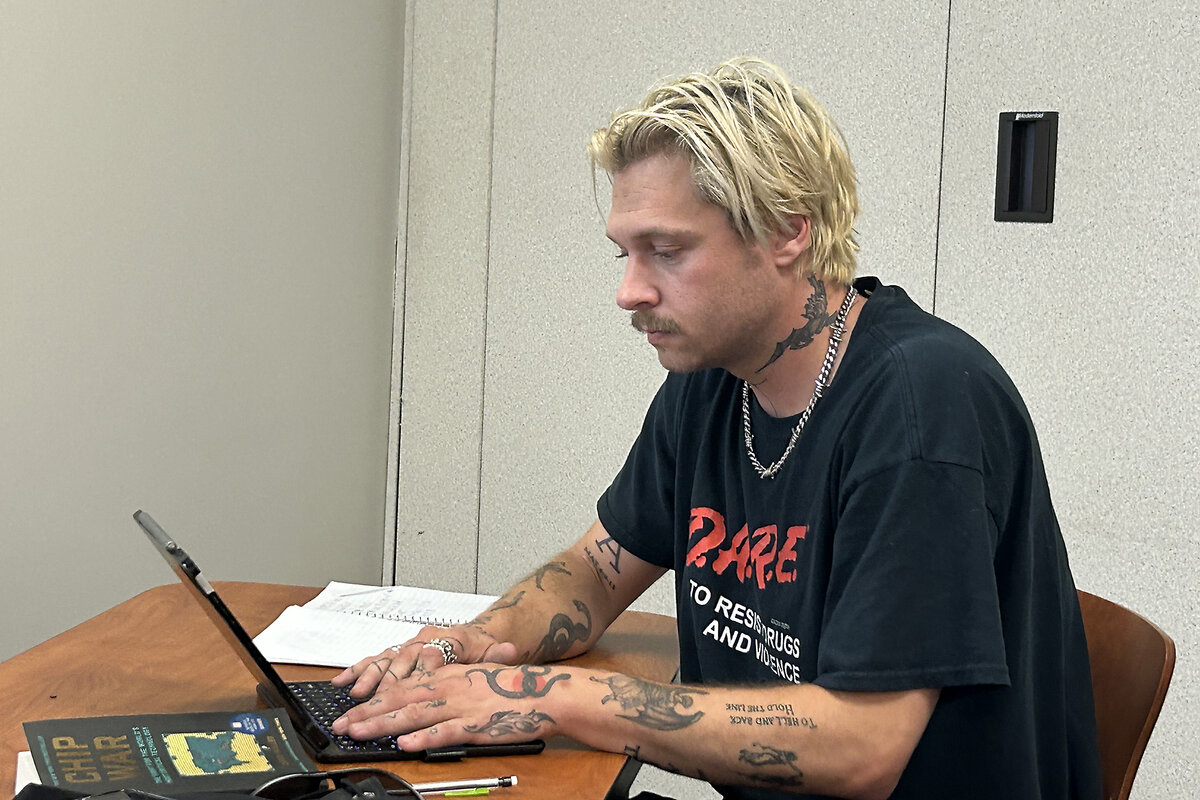

William Muir is interested in Arizona or Ohio, whichever is ready for him first. He’s a line cook at a French restaurant in Upper Arlington, his hometown, just outside Columbus. Mr. Muir is back at CSCC after starting 18 years ago and dropping out.

“It feels really good to be back in school and working toward something that has a higher potential, because before I would go to work and be like, ‘Why am I doing this if I’m not happy?’” Mr. Muir reflects.

He heard about Intel’s move to Ohio during a ride to work.

“My Uber driver and I were talking about how we weren’t making that much money,” Mr. Muir remembers. “She told me about the plant coming, and that they were investing billions of dollars.”

He visited campus a week after that conversation and started the enrollment process. Now he’s three semesters in, hoping to finish an associate degree next year. His teachers have told him he could start at close to $80,000 a year. That’s about $50,000 more than his current salary. He and his girlfriend could marry.

“Ever since I passed the 50% mark in this program, the whole thing seems a lot more doable,” he says. “I realize what I’m doing is pretty neat, and not only that, but I’m fully capable of being able to do it.”

Ira Porter’s reporting for this story was supported by the Institute for Citizens & Scholars’ Higher Education Media Fellowship.