Recent strikes by Israel on Hezbollah and Hamas leaders are part of a global expansion of targeted killings, including by the United States. We examine the legal basis for such operations.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

People have plenty of views on how best to raise children. Norway, the subject of our in-depth story today, has a 63-page law, too, designed to help its very youngest residents find a solid footing in a democratic society.

Mention of the power of play pops up a lot – as does respect and charity, equality and solidarity. You’ll learn, too, about “friluftsliv.” The story will likely make you think about what you’ve done or experienced. Most of all, it brings to the fore one of the most important indicators of a society’s values, especially as it evolves and diversifies: How it cares for all its children.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Boeing factory workers rally: CEO Kelly Ortberg faces mounting pressure to end a bitter strike that has plunged the troubled plane-maker further into financial crisis.

• Indian diplomats expelled: Canada says it has identified India’s top diplomat in the country as a person of interest in the assassination of a Sikh activist there and expelled him and five other diplomats.

• Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences: Prize winners Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and James Robinson at the University of Chicago, have documented that freer, open societies are more likely to prosper.

• Reining in gas prices: California Gov. Gavin Newsom has signed a law aimed at preventing gas prices from spiking suddenly when refineries go offline for maintenance.

• Maine shooting lawsuit: Lawyers representing 100 survivors and family members of victims of the deadliest shooting in Maine history, in 2023, have begun the formal process of suing the Army for failing to stop the tragedy.

( 5 min. read )

As China signals bold moves to revive its economy, all eyes are on its collapsing property market. Can the government restore the confidence of would-be homebuyers?

A deeper look

( 15 min. read )

How best to raise well-adjusted citizens in a democratic society? In Norway, the process starts early, with an emphasis on childhoods that are joyful, secure, and inclusive.

( 5 min. read )

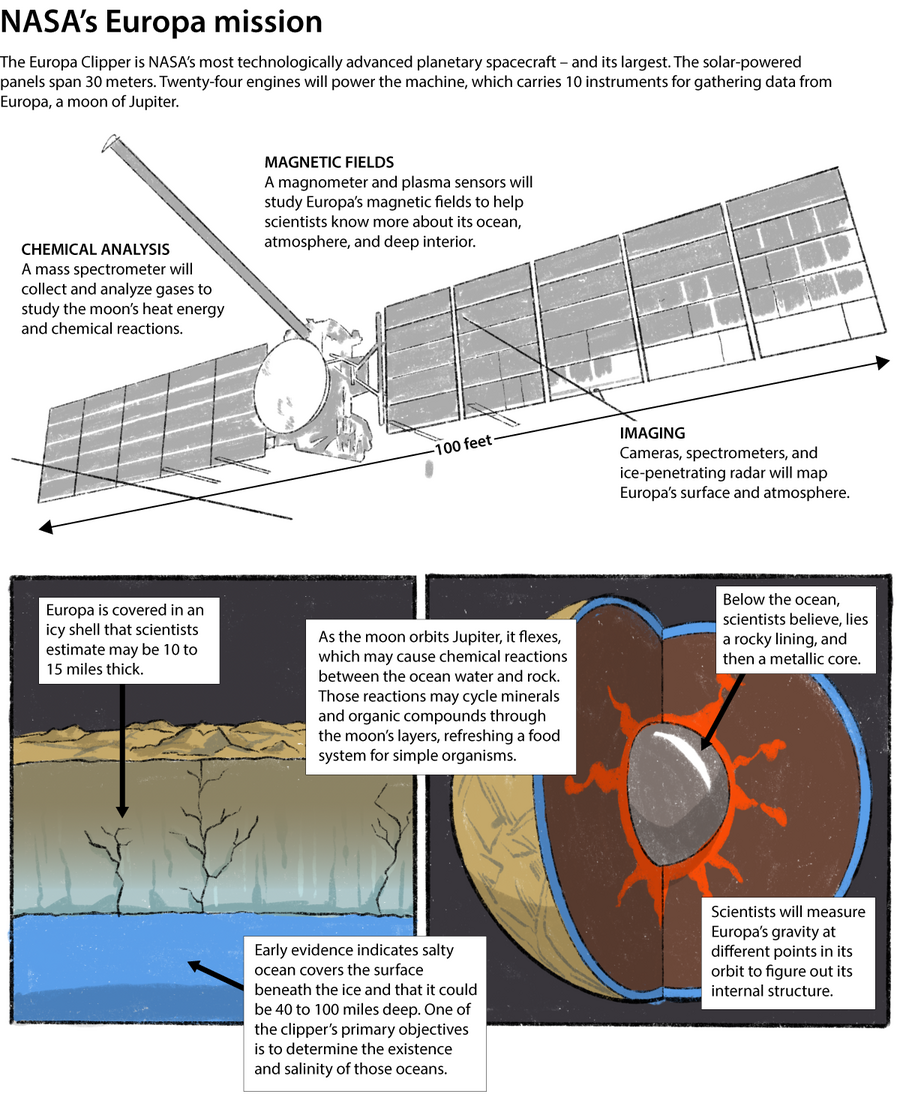

The launch of the Europa Clipper mission to a potentially habitable celestial body – a moon of Jupiter – is a leap forward in the quest to answer one of humanity’s greatest questions: Is there life beyond Earth?

Points of Progress

( 4 min. read )

In our progress roundup, technologies to recover precious resources range from a low-cost water harvester invented in Saudi Arabia, to the new factory in the United Kingdom that is taking gold from old electronics to make jewelry.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

The majority of U.S. presidential contests since 2000 have included a major-party nominee who was not white or male. This year, for the first time, two Black women are running for the Senate, an institution that in 200 years has had only two elected Black female members. Across the United States, roughly a quarter of state legislators are Black, Asian, or Hispanic.

Do the ethnicity and gender of candidates still matter to American voters? The answer is mixed, but probably less than they mattered before.

Polls show a gender gap in preferences for the two presidential candidates. Regardless of ethnicity, majorities of women back Kamala Harris over Donald Trump. Among Black and Hispanic men, however, the former president and the Republican Party have gained ground since previous elections.

Former President Barack Obama admonished Black men last week for not supporting Vice President Harris because of her gender. That premise may be only partially correct. Terrance Woodbury, president of Hit Strategies, a polling firm focused on minority voters, sees an ongoing realignment of Black, Hispanic, and working-class white men based on common economic concerns.

“Democrats have experienced erosion ... amongst Black men in every election since Barack Obama exited the political stage” in 2016, he told The New Yorker. “This is not just a Kamala Harris problem. This is a Democratic Party problem.”

One party’s problem may be democracy’s gain. During her short candidacy, Ms. Harris has focused far more on economic proposals and character issues than on her gender and ethnicity.

“We’re not going to lead with identity in the same way that Hillary Clinton did” in 2016 when she was the nominee, said Aimee Allison, founder of She the People, which supports women of color in political leadership. She told The Associated Press that candidates must now demonstrate that “You have a heart for people who you’re not like ... but deserve to be served by government and deserve representation.”

That approach echoes a lesson learned most recently in Mexico, which elected its first female head of state in June. In recent decades, as women there have achieved a record of expertise in leadership qualities and policy, the country’s still male-dominated culture has softened. The new president, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, is an engineer, climate scientist, and former big-city mayor with a proven record in reducing violent crime.

When a recognition of higher – or even spiritual – qualities “has prevailed,” observed Annie Knott, an American contemporary of the women’s movement a century ago and an early worker in the religious movement behind this news organization, “woman has been accorded her rightful place, at least to the extent of having an opportunity to prove her fitness for sharing in the heroic task of elevating” the human race.

Voters in this U.S. election may be recognizing that qualities of character and ideas define a candidate’s identity rather than identity defining those qualities. Many democracies have already moved in that direction.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

As children of the all-powerful God, we have the freedom and ability to make wise choices.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll take you to the southern tip of Texas, where SpaceX just successfully conducted a historic flight test of its Starship rocket. As the company ramps up, many nearby residents are inspired by the growing commercial space industry – and concerned about collateral damage locally in terms of noise and the environment.