The residents of eastern Ukraine’s Donetsk region have been resilient in the face of the Russian war. But Russia’s introduction of upgraded, highly destructive “glide bombs” is changing civilians’ calculus.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

When is it time to go?

Today, staff writer Scott Peterson plumbs the thinking of residents of Myrnohrad, Ukraine, making heart-wrenching calculations as the front lines of the war draw closer and Russian glide bombs target the cornerstones of their town.

Residents must cope with the daily dissonance of cleaning up a beautiful garden littered with detritus from a nearby bombing, or passing by a joyful family photo lying on rubble-strewn ground.

When is it time to go? Amid war, it’s a profoundly challenging question.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Paris gold: American gymnastics star Simone Biles powered a dominant U.S. women’s team in the finals, with a total score of 171.296.

• Israel strikes Beirut: The Israeli military says it targeted the militant commander accused of being behind the deaths of 12 children and teens in a rocket attack on the Israeli-controlled Golan Heights.

• Venezuela unrest grows: Protests and clashes over accusations of a stolen election have spread after President Nicolás Maduro was awarded a third term on July 29 despite opposition claims of a landslide victory.

• U.S. racial income gap: A study by Harvard University and U.S. Census Bureau researchers found the income gap between white and Black young adults was narrower for millennials than it was for Generation X.

( 7 min. read )

President Joe Biden had resisted calls to reform the Supreme Court. Then came the July decision offering former presidents immunity for any official act.

( 3 min. read )

At the Paris Olympics, Team USA’s swimmers have racked up the medals, building on legendary successes. But athletes from Australia and China have made their own statements.

The Explainer

( 5 min. read )

Although recycling is popular in the U.S., consumers still have questions about the process and its effectiveness. We sort them out here.

Points of Progress

( 4 min. read )

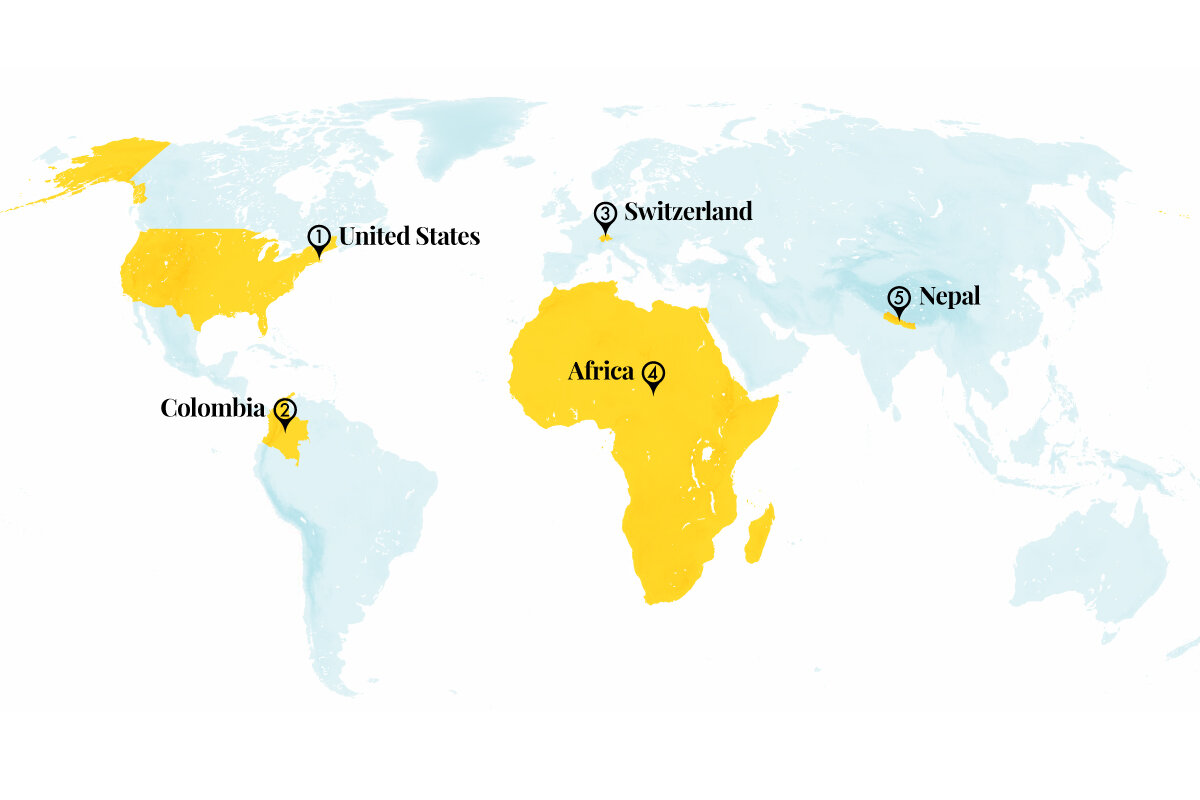

In our progress roundup, we found pioneers west of Boston, where a community became the first in the U.S. to pilot an underground system to replace gas furnaces. And in Switzerland, older women fought in court for protection against climate change.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

The watchdogs of good governance who say democracy is slipping seemed to gain traction Sunday. Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro claimed a hasty victory in a presidential election widely seen as flawed. By the next day, however, his opponents had gathered their own tally of votes, making a case to challenge his grip on power.

“I speak to you with the calmness of the truth,” said Edmundo González Urrutia, the opposition candidate regarded by many – even by Maduro supporters – as the rightful winner.

“A free people is one that is respected,” he added, “and we are going to fight for our freedom ... [with] calmness and firmness.”

His words are an echo of what many other pro-democracy leaders say in countries where rulers are suppressing democratic dissent.

“For us, there’s more than power; there’s truth,” said India’s opposition leader Rahul Gandhi after a strong showing in a recent election.

In dictator-ruled Uganda, opposition leader Bobi Wine defined the role of pro-democracy groups in a similar way. “We’ve been able to put truth on the table,” he said. “We don’t believe in revenge, but we believe in truth and reconciliation.”

In Iran, Narges Mohammadi, the imprisoned activist who won the 2023 Nobel Peace Prize, said the people are “the determining factor in the democracy equation.”

In Belarus, opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya said last year that the people “have chosen the path of non-violence against violence, love against hatred, creativity against brutality, solidarity against confrontation.”

Venezuela is the latest country to find itself midstream in a transition back to democracy. And it may be showing how tyranny unravels. “The superficial appeal of the rise-of-autocracy thesis belies a more complex reality – and a bleaker future for autocrats,” observed Kenneth Roth, then the executive director of Human Rights Watch, in a 2022 article in Foreign Policy.

Around the world, citizens keep affirming that power resides in calming truths, such as accurate vote counts and peaceful displays of equality.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 4 min. read )

Trusting God’s, Spirit’s, view of life enables us to move forward with confidence and gain progress.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

We hope you enjoyed today’s issue. Tomorrow, in addition to other news coverage, we’ll revisit the River Seine, which is still posing problems for Olympians despite a $1.4 billion cleanup.