Olympic glory isn’t just about medals. For these athletes, the honor and joy of competition are their own triumphs. Still, gold would be good, too.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Our profiles today of several Olympic athletes remind me of something we don’t always make space for in our lives: a sense of awe.

The Olympics can be clouded by any number of factors, including cities’ disinterest in hosting, big money, even frustrating and sometimes excessively gooey TV coverage (in the United States, anyway). But then there’s the outsize display of other things: the skill, tenacity, persistence, resilience, and sportsmanship of athletes we’ll first meet Friday at the opening ceremony in Paris. Few of them will make it to the podium. But many will offer us a moment to embrace a delight-filled wonder at what is possible.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 19 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

Secret Service director resigns: Kimberly Cheatle is stepping down from her job after an outcry following the assassination attempt against former President Donald Trump.

U.S. Sen. Bob Menendez resigns: Mr. Menendez bowed to pressure from fellow Democrats in the aftermath of his conviction on corruption charges.

China’s retirement age: China will gradually raise its statutory retirement age, as it struggles to relieve soaring pressure on pension budgets.

Haiti aid: The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, announced $60 million in assistance during a trip to the troubled Caribbean country.

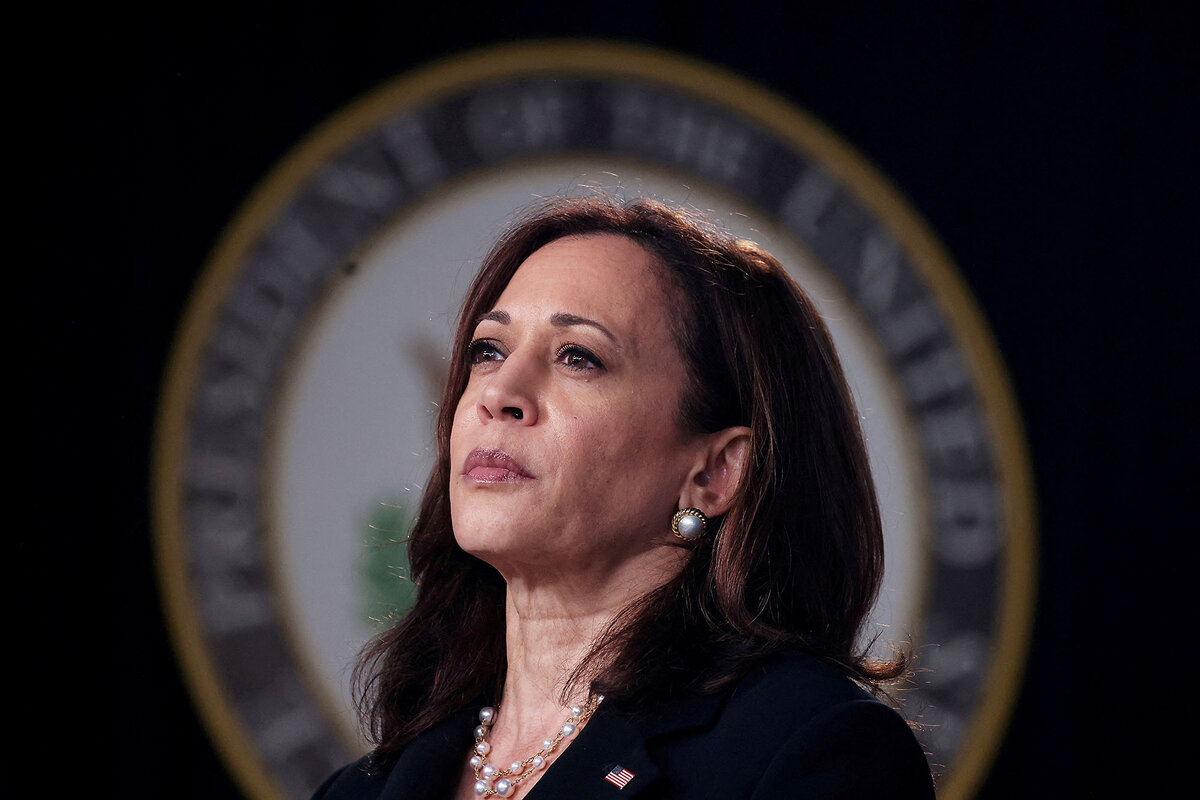

Harris heads to Wisconsin: Vice President Kamala Harris is making her first visit to a battleground state after locking up enough support from Democratic delegates to win her party’s nomination.

( 5 min. read )

U.S. President Joe Biden’s late-stage departure from the presidential race has led to complaints that the Democratic Party is imposing an undemocratic outcome on its voters. Will Republican criticism stick?

( 6 min. read )

Kamala Harris is a household name as vice president, but she’ll be reintroducing herself to voters as she moves toward the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Here are some key facts from her career and personal life.

( 5 min. read )

In the South China Sea, Chinese patrols are disrupting the livelihoods of Filipino fishing communities – and pushing more women into the workforce.

( 3 min. read )

Great reads abound in our 10 picks for this month. Travel to a tropical island, small-town Australia, or even 1950s Iran, without leaving your chair. Or take these books along on your vacation.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

One popular aim in the Olympics is to upend stereotypes, starting with presumed limits on what the human body and mind can do. In every Games, sports records are broken, akin to NASA outdoing past feats in space. But what about social stereotypes? For an example, keep an eye on swimmer Adam Maraana during the XXXIII Olympiad in Paris.

First, though, beware of labels too easily attached to this athlete by journalists. One facile tag is that he is an “Arab citizen of Israel” and the first of that description to compete for his country in nearly half a century. Or that he is Muslim because his father is. Or that he is Jewish because his mother is. (His parents met on a beach in Haifa. Arabs are about 20% of Israel’s population.)

Mr. Maraana does identify as Israeli – the easiest route for him to get into the Olympics other than being a refugee, or via what the Olympics calls universality placement. Yet he also says, “I’m great proof of integration” between Jews and Arabs – a rather bold statement as the world debates what to do in Gaza once the war ends or how to prevent a wider conflict.

Most of all, he sees himself as a walkin’, talkin’ ambassador for two particular values: dignity and respect. “I assume that most people were taught at home what dignity is,” he told Haaretz. “The question is if they were taught what dignity is without discriminating based on religion, race and gender.”

“I was taught that regardless of who’s standing in front of me, he or she deserves my respect,” he said. “Ultimately, I’m ready to talk about the most sensitive issues, and I don’t hold back.”

One of his coaches, Carmel Levitan, says that his hopes of being an ambassador between religions and ethnicities is “a little naive, but it’s beautiful.” Yet within the Middle East, he has lately had plenty of company.

Since 2019, a wave of youth-led protests in several Muslim countries has carried a common complaint about political leaders: Stop divvying up people by religion or ethnicity when sharing power or distributing government services. A 2020 survey of Arab youth found most want public society defined by individual rights and shared interests.

The head of Israel’s Olympic Committee, Yael Arad, wrote on Facebook that Mr. Maraana’s ascent as a swimmer is more than a personal dream. It is also a “vision of coexistence in Israel regardless of religion, race and gender.” And it’s a vision held by someone who swims against stereotypes.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

A growing understanding of everyone’s true, spiritual nature releases us from painful memories of mistakes and hurts.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll have a graphics story on how people are feeling around the globe, based on a 2023 survey. The answers may surprise you.