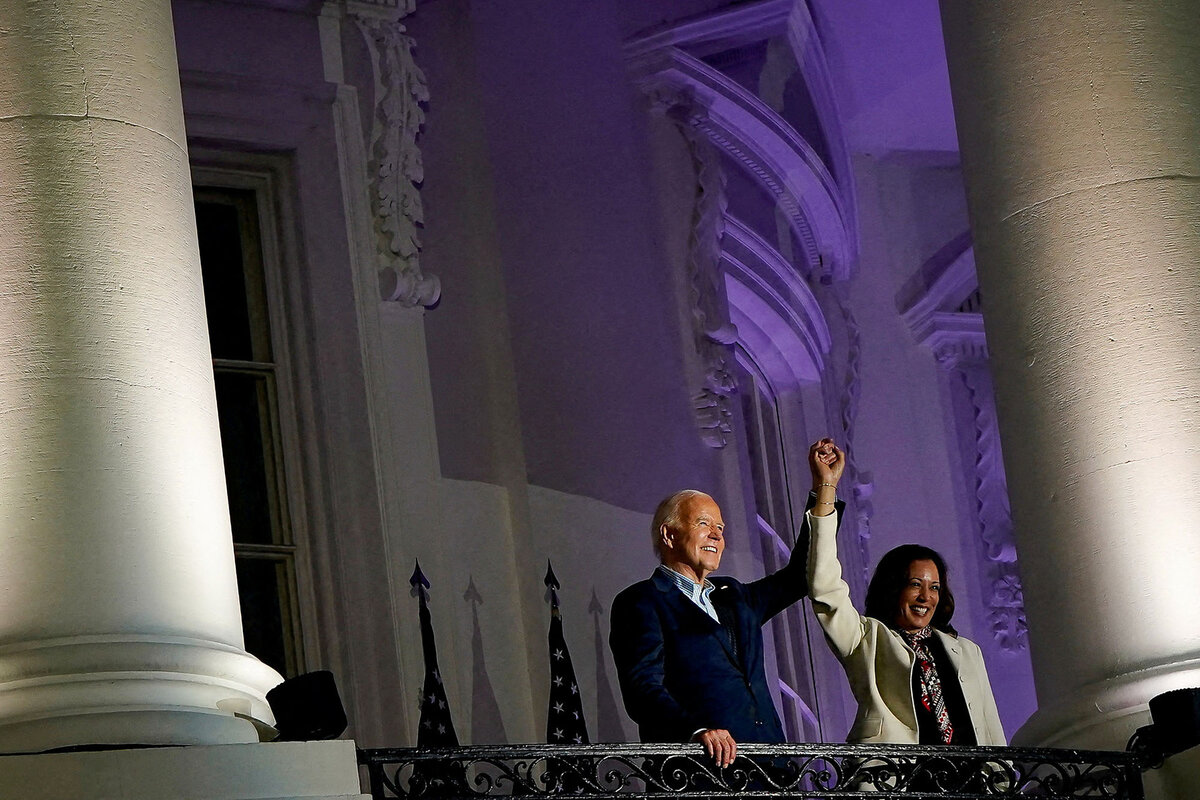

With many Democrats concerned about President Joe Biden’s ability to serve a second term, the spotlight is shining brighter on Vice President Kamala Harris. That gives her an opportunity to reintroduce herself to voters after a rough start.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

People sometimes wonder what heads of state chat about in the less formal moments of a global gathering. Today, members of NATO assembled in Washington to toast the organization’s 75th anniversary – and it’s easy to think that small talk might prove particularly challenging as the political earth moves sharply under their feet at home, overshadowing NATO’s remarkable postwar history.

Howard LaFranchi addresses those dynamics today – and you’ll also see a link to his earlier, in-depth story on NATO. Linda Feldmann and Francine Kiefer, meanwhile, look at U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris in the spotlight. And Robert Klose’s essay about lessons learned as a boy taking on his first job is sure to prompt memories of your own.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Beryl’s wake: Millions of people were without power after Hurricane Beryl hit Texas. They may also face days without air conditioning in dangerous heat. The storm is forecast to bring heavy rains to a swath extending to the Great Lakes and Canada.

• Embezzlement report: Brazil’s Federal Police allege former President Jair Bolsonaro embezzled jewelry worth about $1.2 million during his time in office. He was indicted last week.

• Russian prison sentence: A playwright and a theater director each got six years for a play about Russian women who marry Islamic State fighters that authorities said was “justifying terrorism.” The case was the most prominent prosecution of cultural figures since Moscow invaded Ukraine in 2022.

• Kyiv children’s hospital: The head of the U.N. Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine said the July 8 strike on the Okhmatdyt hospital was likely caused by a direct hit from a Russian missile.

• Peace mission: Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán paid an unexpected visit to Beijing days after talks with Russia’s Vladimir Putin angered some European Union leaders.

( 4 min. read )

Joe Biden’s leadership of NATO in addressing the challenges posed by Russia and its war in Ukraine has reassured U.S. allies and been a centerpiece of his presidency. His debate performance raises uncomfortable questions.

( 5 min. read )

The United Kingdom’s July 4 election revealed that the country’s smaller parties are winning a growing share of the popular vote, even as the two big parties dominate Parliament. So citizens are increasingly in favor of making the electoral system fairer.

( 5 min. read )

The return of pandas to the United States is sparking a new wave of “panda-monium,” highlighting the bears’ enduring power to shape China’s foreign relations and global wildlife conservation.

( 3 min. read )

As our essayist discovered at the tender age of 12, the old adage is true: Experience really is the best teacher.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the member states of NATO have bolstered their shared military readiness across Eastern Europe and admitted Sweden and Finland to their ranks. Now world leaders gathering in Washington this week to mark the 75th anniversary of the alliance plan to go further. They expect to deepen their military support for Ukraine and extend security cooperation with like-minded partners in Asia.

These measures mark a push within NATO to apply its long-standing approach to building peace through “defense and deterrence” to a new age of threats. Yet within the alliance, some members are also pushing safeguards for collective security that do not rely on military hardware. One national leader, Finnish President Alexander Stubb, said debates about global security are overly based on planning for war. “We also need to start talking about peace and a pathway towards peace,” he told a forum of policymakers in Helsinki last month.

A bilateral security agreement signed Monday between Poland and Ukraine enumerates what Mr. Stubb may have in mind. It sets a “shared responsibility for peace” on “commonly shared principles of democracy, rule of law, good governance, [and] respect for fundamental freedoms and human rights.”

That is just one of 19 such agreements that individual NATO members have forged with Ukraine. While many include supplying Kyiv with weapons, they also include measures to strengthen governance and ensure that children in war zones keep going to school. That dovetails with Sweden’s national security strategy, which links peace to the security of girls and women.

Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, one of Europe’s foremost hawks in response to Russian aggression in Ukraine, argued that encouraging corruption reform in Ukraine is as important as sending it arms. Her argument corresponds with a bilateral security framework the Biden administration signed with Ukraine last month. It encourages “implementation of Ukraine’s effective reform agenda, including strengthened good governance, anti-corruption, ... and rule of law.”

These building blocks, argued Michael Doyle, professor of international affairs at Columbia University, explain why liberal democracies remain peaceful – at least with each other. “When governments are constrained by international institutions, when political elites or the electorate are committed to norms of liberty, when the public’s views are reflected through representative institutions, and when democracies trade and invest in one another, conflicts among republics are peacefully resolved,” he wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine last month.

In a 2021 speech to the United Nations, U.S. President Joe Biden put that more succinctly. “The future will belong to those who embrace human dignity, not trample it.” Russia’s war in Ukraine is expanding NATO’s approach to security beyond arms. It sees peace rooted in human dignity as unshakable.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 4 min. read )

As we look to God, divine Spirit, for an understanding of what we truly are, our innate goodness, freedom, and abilities come to light.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we start a three-part series on efforts in the United States, Canada, and Portugal to better help people struggling with addiction – including by having law enforcement and treatment providers work together. I hope you’ll take a look.