The American president is facing perhaps the biggest crisis of his political career, a make-or-break moment for his 2024 reelection campaign. The Monitor accompanied him on the campaign trail this weekend. Here’s what our reporter saw.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Not so long ago, we ran a series called Navigating Uncertainty. That also makes a good title for today’s Daily.

Will President Joe Biden drop out of the presidential race? We have two takes – an explainer on all the potentially complicated logistics and an up-close view of the president from the past three days.

Can the French resolve their election chaos? Can Iran’s new reformist president bring change? We look into both topics and stand back to examine a U.S. Supreme Court finding its identity after the upheaval of 2022’s abortion ruling.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Russian missile strike: Dozens of Russian missiles blast cities across Ukraine, striking apartment buildings and a large children’s hospital in the capital.

• Israeli offensive: Israeli tanks advance into the heart of Gaza City as Israel orders Palestinian civilians to evacuate neighborhoods after a night of bombardments.

• Boeing plea deal: The U.S. Justice Department says Boeing has agreed to plead guilty to a criminal fraud charge stemming from two deadly crashes of 737 Max jetliners.

• Myanmar rebels advance: One of Myanmar’s most powerful ethnic minority groups battling the military government says it captured an airport, marking the first time resistance forces have seized such a facility.

( 7 min. read )

Overturning Roe v. Wade was just the first step for conservatives eager to undo what they regarded as past judicial mistakes. With its rulings this term, the Supreme Court has declared itself in charge of implementing that vision.

( 5 min. read )

France staved off its most immediate crisis: a parliamentary takeover by the far right. Now it moves on to the next one: how to assemble a government in a fractured political landscape where “compromise” is a dirty word.

The Explainer

( 5 min. read )

After weeks of hand-wringing about whether replacing Joe Biden on the 2024 ticket would do more harm than good, Democrats are now turning to how to make the switch as seamless as possible.

( 5 min. read )

The one reformist candidate allowed to stand for president in Iran faced severe hurdles, such as a public largely unwilling to confer legitimacy on the regime by voting. But he won because his everyman persona and a message of improving lives resonated.

Points of Progress

( 4 min. read )

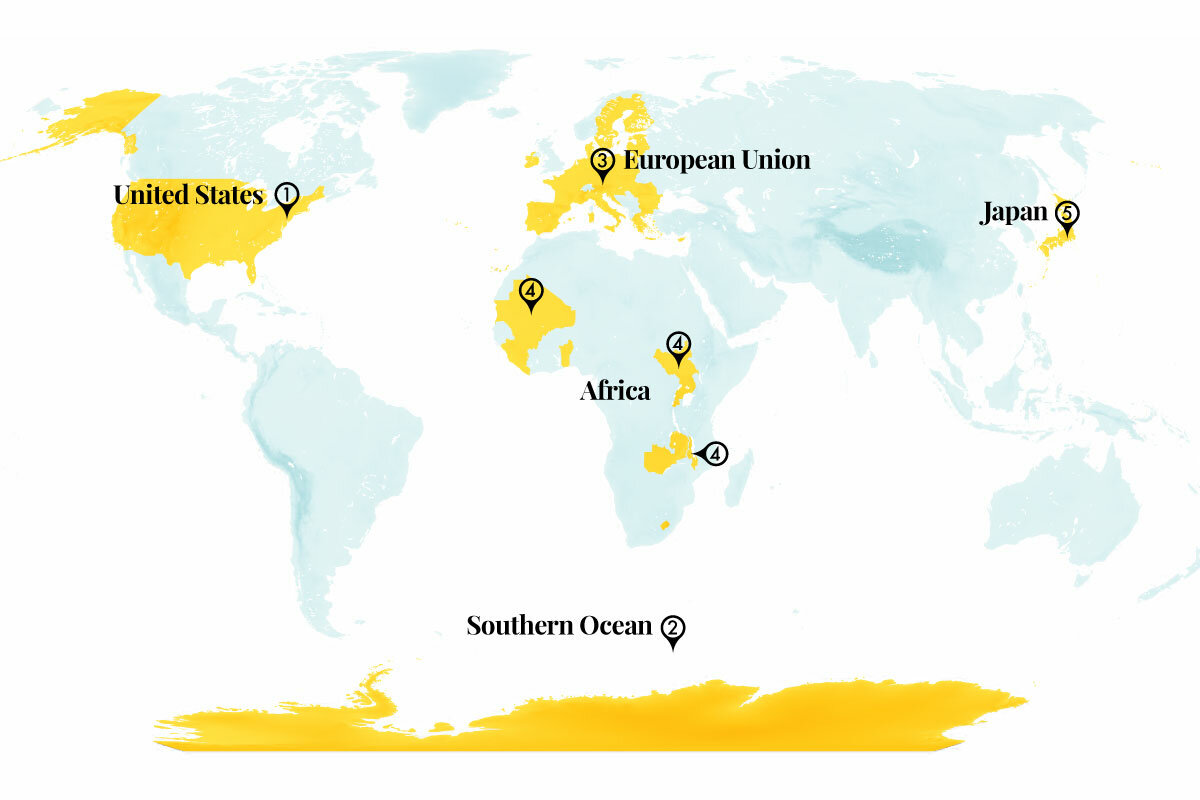

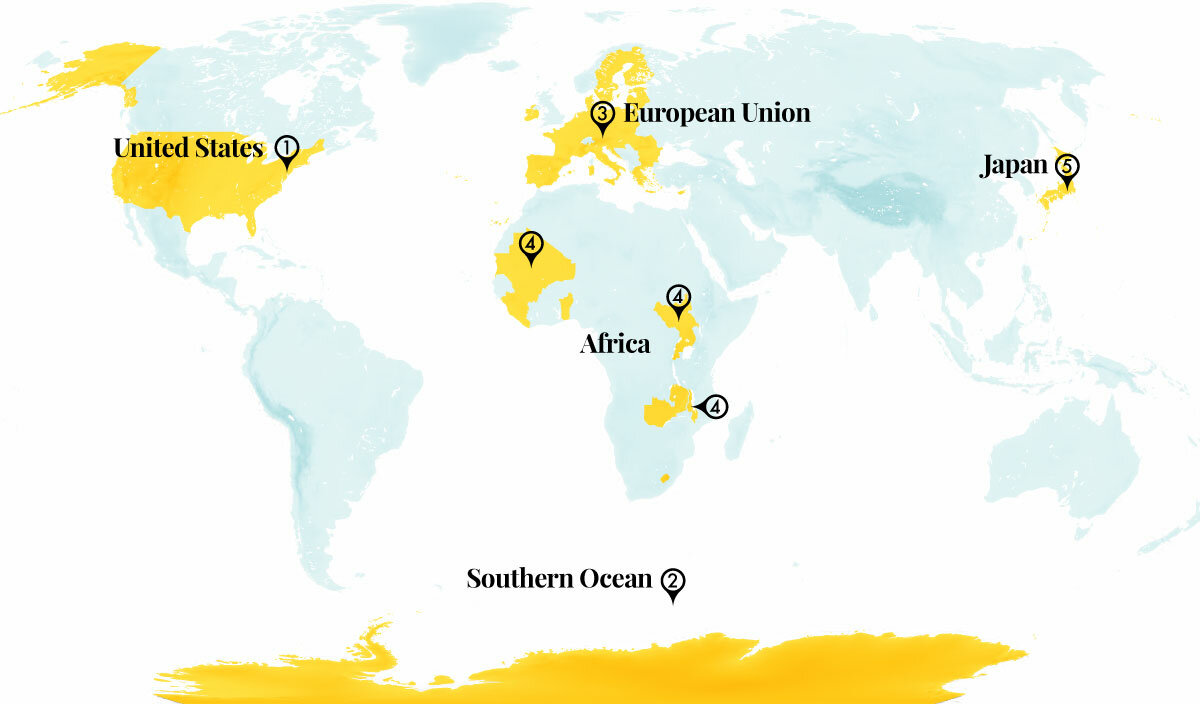

In our progress roundup, a study finding more blue whale sounds in the Southern Ocean may indicate recovery of the species. And around the world, playgrounds designed for all ages not only are pure fun, but also promote social relationships in public spaces.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

n a clear message to their ruling clerics, more than half of Iranian voters chose not to cast ballots in a highly engineered election for president on July 5. “I want a free country, I want a free life,” one university student in Tehran told Reuters in describing her reason not to give legitimacy to an unpopular regime.

Those who did vote sent a similar message, one that might now also influence Iran’s violent campaign across the Middle East to be the guide and guardian of all Muslims.

Voters rejected the regime’s chosen hard-line candidate, Saeed Jalili, opting instead for a conservative reformer, Masoud Pezeshkian. While the winner seems loyal to Iran’s religious authoritarianism, Mr. Pezeshkian did call for citizens’ rights and a “partnership” with the people.

A former heart surgeon and health minister, he promised to end violent enforcement of a dress code for women as well as restrictions on internet access. “I am religiously opposed to any kind of coercion or harsh treatment of any human being,” he stated. In addition, he seeks talks with the West to end crushing economic sanctions aimed at curbing Iran’s nuclear program.

Any forceful attempt at reform by Mr. Pezeshkian could be one more challenge to supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and to a 45-year doctrine in Iran that a Shiite “jurist” must have ultimate authority in the Islamic Republic. That doctrine was directly challenged during a mass uprising in 2022 led by hijab-shunning women under the slogan “Women, life, freedom.” A poll that year showed that 72% of Iranians oppose the head of state being a Shiite religious leader.

The election was the first since those protests and came during a volatile political moment. Factions within Iran are jockeying to pick the heir to the 85-year-old supreme leader. The succession struggle only adds uncertainty to the future of Iran’s theocracy.

Many Iranians now point to neighboring Iraq, where the most popular Shiite cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, prefers free and fair democracy without direct political control by religious figures. Mr. Sistani openly opposes Iran’s model, preferring instead that clerics play a quiet, spiritual role. The Shiite branch of Islam is a minority in the Muslim world, which is majority Sunnis. Yet in both Iraq and Iran, Shiites are the majority.

Mr. Pezeshkian acknowledged that his reforms face resistance. “A difficult road is ahead. It can only be smooth with your cooperation, empathy and trust,” he told Iranians after the election on social media platform X. Perhaps in recognition of the low voter turnout, he added, “Do not abandon me.”

The new president may also recognize that most Iranians don’t believe reforms are possible without regime change – as well as an end to Iran’s expensive meddling in the region. “The single most liberating event for the Middle East,” stated Tony Blair, a former British prime minister, “will come when the Iranian people finally have their freedom.” For Iranians who did not vote in the election and even for those who picked a reformer, their quiet protest was an expression of freedom.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

Recognizing that we are all capable of living up to our God-given goodness and integrity equips us to see and experience that goodness more consistently.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow, when we look at the past trials and triumphs of U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris. What do they suggest about how ready she is to step up and run a last-minute presidential campaign, if required?