As President Joe Biden tries to shore up Black support against inroads by former President Donald Trump, a decline in Black church attendance may pose a key challenge – depriving the Democratic Party of an unofficial organizational arm that has helped get voters to the polls for decades.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Israel’s tactics in Gaza in response to the Oct. 7 cross-border attack by Hamas militants have pushed civilians there to the brink. Gaza’s health ministry says that more than 35,000 Palestinians have been killed. Israel justifies its push to eradicate Hamas in defense of its own right to exist.

Monitor editors continue to talk about what international law says about war’s “collateral damage” and about “the principle of proportionality.”

These are legal issues – complex protocols, with wiggle words – that also contain moral components, including ones codified in the combatants’ respective religious texts. Today, we turn to Ned Temko, whose Patterns column thoughtfully explores both.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 9 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Putin-Kim handshake: On his first visit to Pyongyang since July 2000, Russian President Vladimir Putin signs an agreement with North Korea’s leader that includes a mutual defense pledge. Mr. Putin linked the move to the West’s support for Ukraine.

• Hajj amid heat: Hundreds of people are believed to have died during this year’s Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia as the faithful faced intense high temperatures at Islamic holy sites.

• Ten Commandments law: Louisiana becomes the first state to require that the Decalogue be displayed in a “large, easily readable font” in all public classrooms, from kindergarten to state-funded universities. The U.S. Supreme Court previously ruled such laws unconstitutional.

• Snapchat settlement: The social media firm will pay $15 million to settle a lawsuit brought by California’s civil rights agency, which accused it of discriminating against female employees, failing to prevent sexual harassment, and retaliating against complainants.

• Stonehenge sprayed: Two climate protesters are arrested for spraying orange paint on the ancient Stonehenge monument in southern England, and charged on suspicion of damaging the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

( 5 min. read )

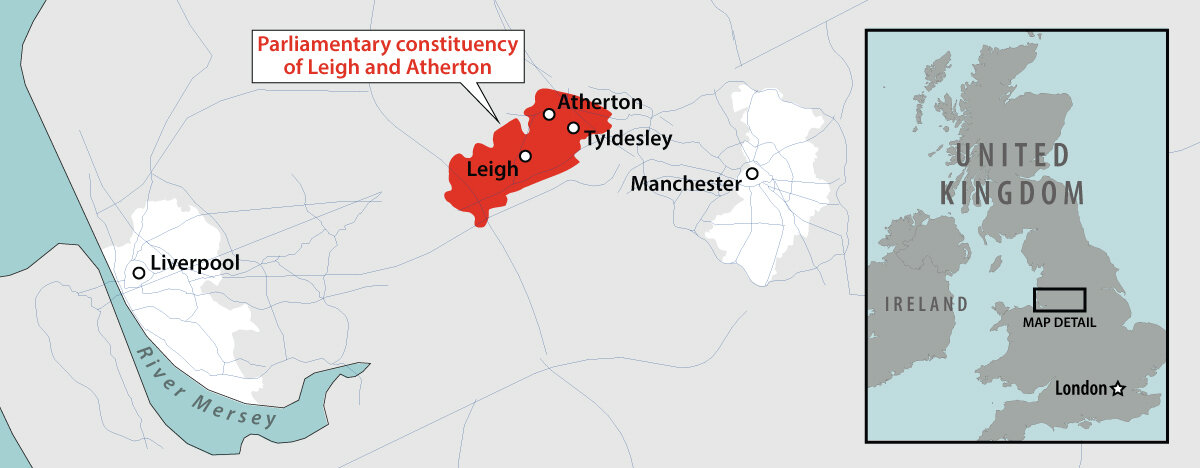

In 2019 elections, Britons living in “red wall” constituencies felt disrespected by the Labour Party, which helped lift the Conservatives to victory. Now, they may decide the election again – and they feel it’s the Tories who aren’t doing right by them this time.

Patterns

( 5 min. read )

How heavy do civilian casualties have to get before they are judged too severe to justify? Israel is finding it hard to explain to the world its tactics in Gaza.

( 5 min. read )

This week, baseball is celebrating the Negro Leagues legacy in Birmingham, Alabama. The death of hometown hero Willie Mays has underlined his own incomparable legacy and how his life intertwined with Birmingham, baseball, and Black America.

Books

( 2 min. read )

If you’re looking for lively reads to tuck into your suitcase this summer, we have you covered. The Monitor’s 10 best books of June, from biographies to family sagas, are sure to keep you turning pages.

In Pictures

( 2 min. read )

Children in Colombia’s impoverished Chocó region are often preyed upon by violent armed groups. In the Rugby 4 Chocó program, children learn a different way to belong.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

Last week, Baltimore reopened its port to vessel traffic. The city can now turn its full attention to replacing a critical bridge that collapsed in March after being struck by a cargo freighter. June 24 marks the deadline for proposals to build a new span.

Restoring a vital piece of infrastructure offers an opportunity to rethink how citizens can be involved in redesigning their communities, especially at a time of mass urbanization and climate change. One proposal would replace the fallen Francis Scott Key Bridge with a lighter span suspended by cables. Its towers would be set farther apart, creating a wider lane for ships. The design, which reflects innovation and cooperation, was a collaborative effort between an Italian architect and a French structural engineer. The materials would have a low carbon footprint, and new communication technologies would better connect outlying communities with the city center.

The plan was pitched by the same company that rebuilt a bridge that collapsed in Genoa, Italy, in 2018. That restoration was completed in just 15 months, well short of the average time span for large infrastructure projects in Italy. Several factors combined to create “an ethical momentum of great stature,” Maurizio Milan, the designing engineer, told Euro News. Enhanced government transparency helped protect the project from corruption. Residents and construction workers were consulted in the designing the structure. Such steps reflect lessons learned after disasters elsewhere, such as in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and in Japan following the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

Residents and local officials in Baltimore have already stressed that, in replacing the Key Bridge, civic values matter as much as structural design. That has included compassion for the families of workers who died in the bridge collapse and economic support for those whose jobs ground to a halt while the port was closed.

The tragedy also sparked a vibrant debate about healing the city’s racial issues. Francis Scott Key penned the words of the national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner.” As a lawyer, he represented enslaved people seeking their freedom in court. But he was also a slave owner himself.

Now some residents see a new bridge as an opportunity to express a more inclusive identity. Speaking at a community forum, Carl Snowden, head of the Caucus of African American Leaders, observed, “What an incredible moment in history we find ourselves in.” A new bridge in Baltimore may span more than water. It may also arc the city’s skyline with tighter bonds of community.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

Seeing ourselves and others as we really are, made in God’s image, brings healing.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for reading today. For tomorrow, we’re working on a counternarrative about Haiti, looking at issues – including around schools – that are being met head-on, and with resilience.

And on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast, Kendra and I will be back on mic with an update of her June 2022 story about the gains being made by women 50 years – now 52 years – after Title IX.