Working-class ‘red wall’ voters decided the last UK election. How do they feel now?

Loading...

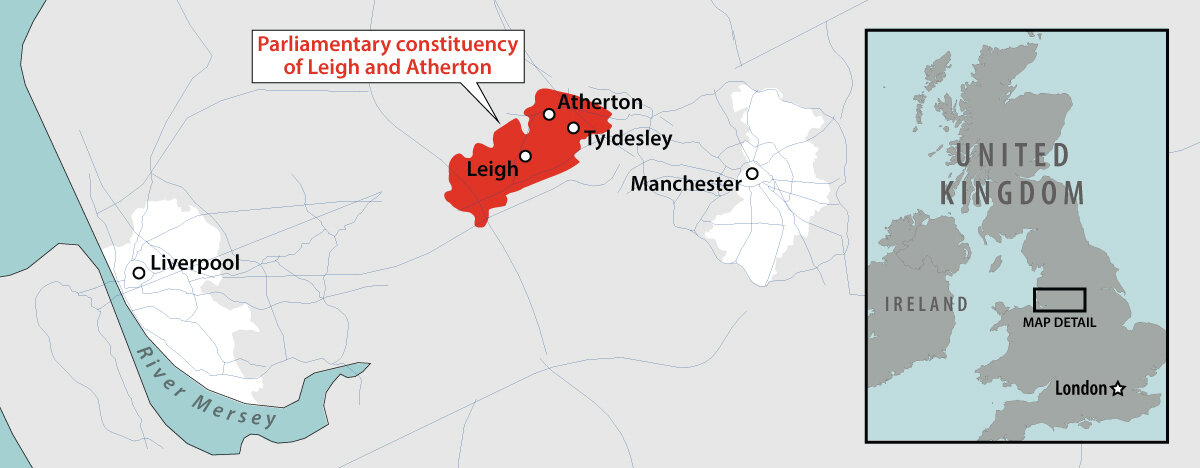

| Tyldesley, England

When the United Kingdom heads to the polls July 4, all eyes will be on towns like Tyldesley.

With its tangle of narrow streets and red brick homes dating back to the area’s industrial heyday, Tyldesley is typical of towns across England’s northwest. Labour Party candidate Jo Platt has already spent weeks campaigning here, diligently pushing glossy leaflets into letterboxes and engaging in doorstep conversations with voters.

“We need to give a little bit of hope back to the country. I think that’s what we’ve lost,” she says earnestly, already walking to her next canvassing event. “We’ve lost pride in our towns. If we’re fortunate enough to get into government, then I hope that’s something that we can bring back.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn 2019 elections, Britons living in “red wall” constituencies felt disrespected by the Labour Party, which helped lift the Conservatives to victory. Now, they may decide the election again – and they feel it’s the Tories who aren’t doing right by them this time.

Labour is campaigning hard here. Once it was all but given that the traditionally left-leaning party would win the votes of working-class, industrial towns like Tyldesley. Then came 2019. The area’s constituency switched allegiances to the opposing Conservatives, ending decades of Labour domination.

Tyldesley was not alone. The 2019 election saw a landslide of small towns across England’s north and Midlands as well as in Wales – an area often described as the “red wall” in honor of Labour’s traditional colors – vote in Conservative members of Parliament, many for the very first time.

The collapse of the red wall was a key factor in pushing then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson to 2019 election victory with an 80-seat majority. But five years later, with Conservative approval ratings rapidly tumbling and Labour looking at overwhelming gains in Parliament, it’s these seats – and accordingly, their voters – that are likely to push Labour across the finish line.

Identity and the red wall

The legend of the red wall – and its 2019 collapse – is tightly bound to an idea of British political tribalism. Throughout the 20th century, northern, working-class voters were seen as loyal Labour devotees, while rural, more affluent areas were judged to be unquestioning Conservative heartlands.

The 2019 election brought new political divisions to the fore, with old class divides overshadowed by issues such as Brexit, when the U.K. left the European Union. Many red wall areas – towns that too often felt overlooked and forgotten in a new era of globalization – had voted to leave the EU, but were concerned that Labour would not honor the referendum results. In Tyldesley, the mood soured in the run-up to the 2019 vote. Local Labour councilor Jess Eastoe, who has been handing out leaflets with Ms. Platt, describes being verbally assaulted and spat at.

“The political wrangling over Brexit forced many people to choose between their EU identity [as a ‘leaver’ or a ‘remainer’] and their party identity,” says David Jeffery, a senior lecturer in British politics at the University of Liverpool. “Most studies show that, until quite recently, the EU identity was held much more strongly. Brexit really broke down this strong loyalty toward Labour.”

But that is now changing. As of June 13, just over three weeks before the election, the Conservative Party was polling at just 26% for the Leigh and Atherton constituency of which Tyldesley is part, compared with 50% for Labour. Similar figures are being seen across red wall seats, many of which are projected to fall back under Labour control.

“Of the red wall seats, I’d be surprised if more than a handful stayed with the Conservatives,” Dr. Jeffery says.

“The Conservatives have done nothing”

The Conservatives’ fall from grace across red wall towns has a regional accent. Across Wales and northern England, many voters feel cheated by shortfalls in the government’s “leveling up” plan, a targeted program supposedly designed to help balance regional inequalities between London and other U.K. regions.

The program was a key part of the Conservatives’ promise when they won red wall seats in 2019; at that year’s party conference, then-leader Mr. Johnson vowed that “leveling up” initiatives would repay the region’s trust.

There has been little, however, in the way of results. The government’s flagship plan for a high-speed train line between London and Manchester, HS2, for example, was canceled in October 2023. (The line will instead stop at Birmingham, 100 miles farther south.) Similar policies, such as reducing regional differences in life expectancy or building 40 new hospitals by 2030, have also fallen flat.

Discontentment in towns like Tyldesley also mirrors concerns seen across the country as a whole. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is unpopular, and after a flurry of four Conservative leaders in just over six years – including Liz Truss, who spent just 44 days in office and remains best known for being compared to a lettuce – there is a dearth of likely replacements. Meanwhile, the party’s rhetoric of fiscal austerity is wearing thin after 14 years, particularly against a background of inflation and rising prices.

“The Conservatives have done nothing,” Tyldesley resident Charlotte Steel says when asked who she’ll be voting for in the election. She’s particularly worried about a health and social care system that has been hit by repeated Conservative funding cuts, and says that she’ll be supporting Labour. “This government doesn’t care about people.”

The cost of living in particular is on everyone’s lips. Doorstep issues focus on local infrastructure: People are desperate for more housing, but the new estates being hastily erected are too expensive for locals and serve commuters from nearby Manchester instead.

Local schoolteacher Paul Crowther remains undecided, but is already sure that he won’t be voting Conservative either. The party’s leader, Mr. Sunak, is simply out of touch with the needs of local people, he says. “We just need more funding,” he says, “For the NHS and for education.”

Labour rebounding?

It’s voters like Mr. Crowther that Labour hopes to bring back into the fold. In order to do so, its manifesto has introduced new themes, such as pledges to create a “new Border Security Command” and “crack down on antisocial behavior,” as well as plans to recruit more teachers and promises of economic stability.

Critics have accused the party and its leader, Keir Starmer, of moving away from Labour’s left-wing roots and heading for the political center. Yet the move – a deliberate break from the policies of former leader Jeremy Corbyn, who was seen by many small-town voters as too radical – seems to be resonating.

Mr. Starmer may not be wildly popular, but he is a safe option – and after years of political upheaval and an increasingly disliked government, that might just be a winning formula.

“People are worried about issues that affect this town, like drugs and petty crime,” says Ms. Eastoe, the Labour councilor. “We need to put the boring back in politics. We’re running a country, not a circus.”