Israeli hostages’ families and Palestinians in Gaza are on opposite sides of the war yet on the same taxing emotional roller coaster. So how to maintain hope? As one interviewee put it, “We are all human beings at the end of the day.”

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Listen to the people of Israel and Gaza in today’s remarkable story by Taylor Luck and Ghada Abdulfattah. They’re all saying one thing: It’s time for humanity to have a seat at the table.

One can debate the merits of war. But one cannot debate the effects of war and destruction, which destroy trust, too. Yet without trust, what peace can find any lasting foundation?

People in Israel and Gaza are saying the time for trust-building has come. That, in many ways, will be infinitely more difficult than achieving a military objective. But also infinitely more powerful.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 7 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Biden’s China tariffs: The Biden administration plans to put new tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, advanced batteries, solar cells, steel, aluminum, and medical equipment.

• Arizona abortion decision: Arizona’s highest court gives the state’s attorney general another 90 days to decide further legal action in the case over a 160-year-old, near-total abortion ban.

• “Foreign agents” bill: The Parliament of the nation of Georgia passes a bill that would require organizations receiving more than 20% of their funding from abroad to register as agents of foreign influence.

• Roman Polanski cleared: A French court acquits the filmmaker of defaming British actor Charlotte Lewis, who had accused him of sexual assault.

( 6 min. read )

If Mercedes employees in Alabama vote this week to join the United Auto Workers, it may signal an important shift in America’s most union-resistant region.

( 5 min. read )

“Golden visas” are meant to offer quick access to residency in a country in exchange for a large investment. But governments are now wondering: Is that sort of deal beneficial to their societies?

A deeper look

( 12 min. read )

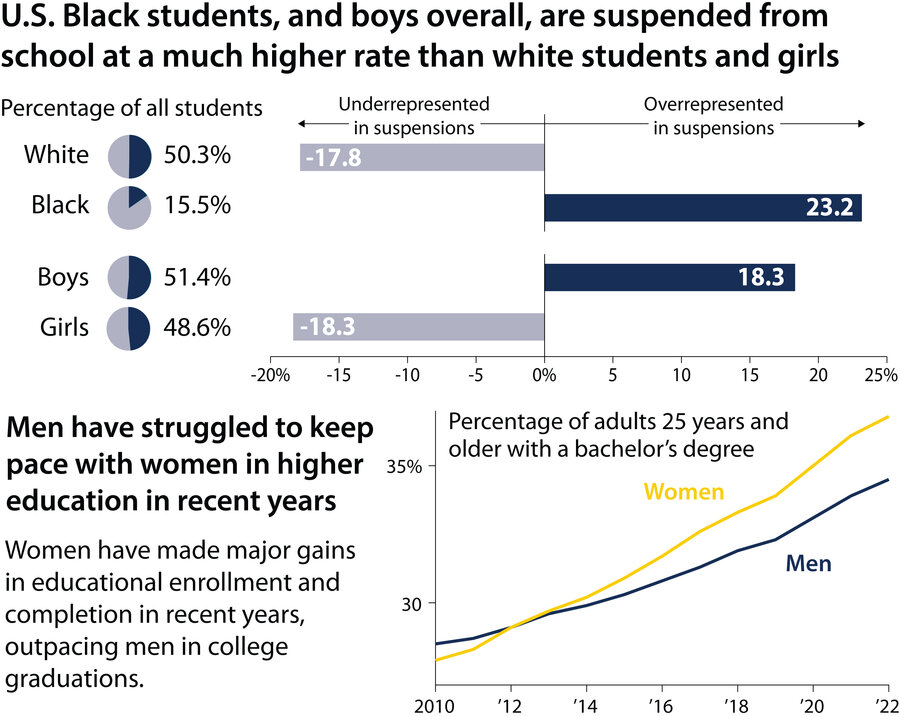

Boys are expected to be tough and independent. But society’s emphasis on these qualities can leave them feeling adrift and alone. Parents and educators are finding ways to help boys cultivate emotional connections.

Essay

( 4 min. read )

The desire to capture natural beauty, whether in a photograph, a painting, or even a perfume, is intrinsic. But in that quest, we sometimes lose sight of a central tenet: Nature’s ephemerality makes it all the more enchanting.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

Readers of the French newspaper Le Monde were confronted with a striking image on the front page Tuesday. It showed 100 public figures with personal stories of sexist or sexual violence implicating some of their country’s most venerated institutions – cinema, government, media, hospitals, and churches. The paper called the visual “unprecedented in our history.”

After years of halting public debate, France may be at a turning point on an issue that challenges some of its deepest social and cultural mores. Rather than unraveling French identity, however, the opening of a more honest public reckoning reveals a society striving to renew its core values of equality and individual dignity.

“We are at the beginning of a transition ... a very profound cultural change,” said President Emmanuel Macron in an interview with Elle magazine last week. “The first stage is that of the liberation of speech, after all these years of suffering and unsaid things. With this listening, grant freedom, trust and kindness to the victims. ... When systems – whether professional, religious, structural – are organized as systems of humiliation, of domination, they betray our values and sully us all.”

The #MeToo movement that catalyzed public debate about sexist and sexual violence in the United States several years ago encouraged intermittent scrutiny within France. But the issue has gained new momentum in recent months since an actor named Judith Godrèche accused two of France’s most prominent directors of abusing her on set when she was teenager. She has addressed Parliament and spoke at the César Awards, France’s equivalent of the Oscars. A documentary film she wrote and directed on sexual violence debuts this week at the annual Cannes Film Festival, which opened Tuesday.

Her advocacy has broken a dam. More victims are speaking out. Their defenders face fewer attacks on social media. Parliament has agreed to form a commission on sexual violence against minors in various cultural sectors, including fashion, at her request. “The difference now,” Clémentine Poidatz, another French actor, told The New York Times recently, “is people are listening.”

That receptivity coincides with mounting evidence of wider changes in attitudes about equality and acceptable behavior within French society. The film industry is embracing changes that create safer working conditions for actors involved in romantic scenes. In March, France enshrined reproductive rights in its constitution. Younger women are rejecting workplace taboos around feminine hygiene. Vocal critics of sexual violence include the ministers of sport and the armed forces. Mr. Macron has promised a comprehensive bill later this year that would, among other things, redefine France’s legal concept of consent.

Societies are not static. They adopt higher standards when public debate results in “improved interpersonal understanding ... increased respect among participants ... [and] better solutions to a variety of practical, moral and intellectual problems,” a 2019 study on social change published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology concluded. For France, and French women in particular, an honest dialogue marks a renewing of equality, fraternity, and liberty.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

Knowing the truth that we are all the children of divine Love helps us see more of the safety and harmony that are all around.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow. Our Africa correspondent, Ayen Deng Bior, takes a deeper look into the trend of harsh anti-LGBTQ+ laws sweeping across the continent and finds questions around “Africanness” and influence beneath the surface.