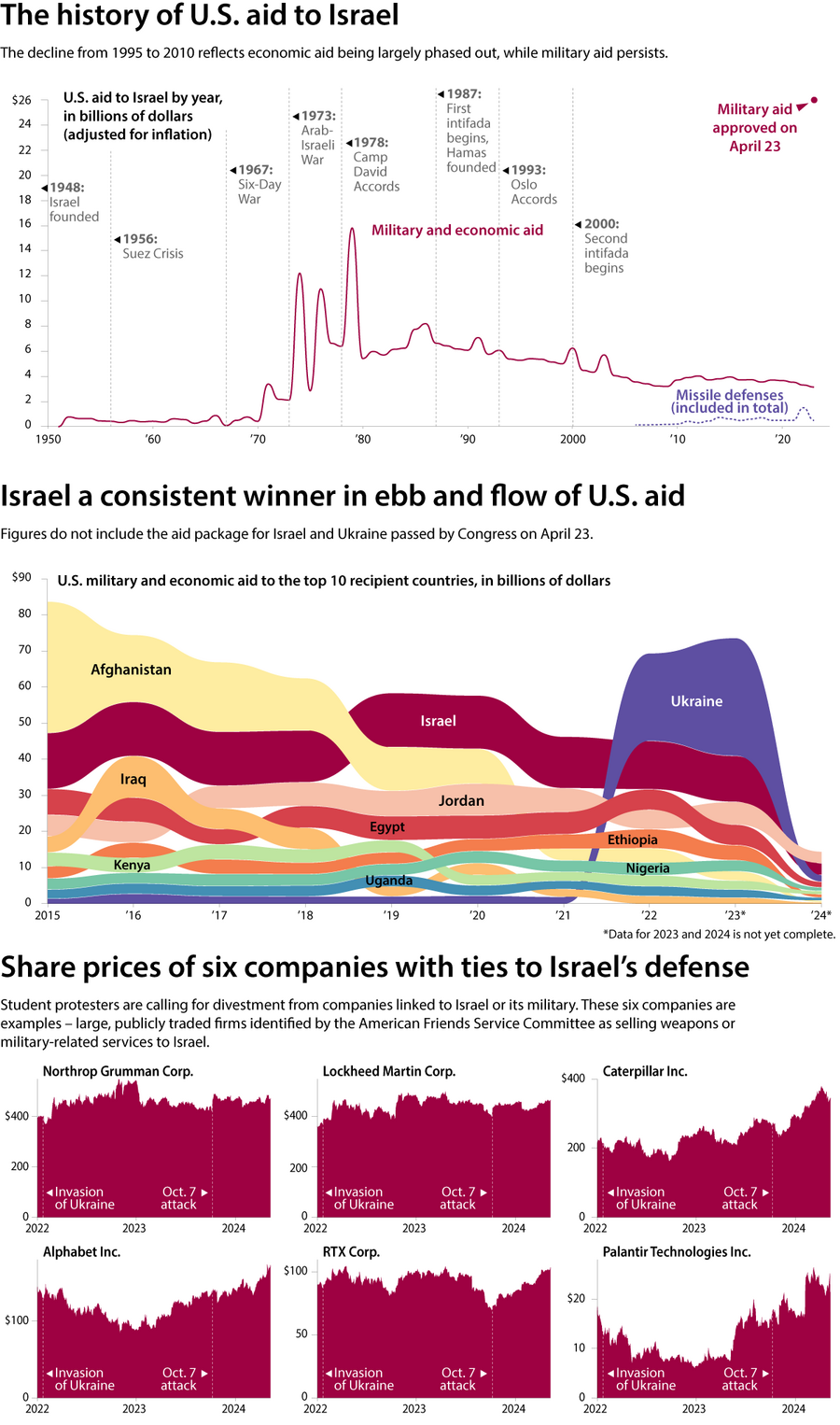

The role of the United States as a major backer of the Israeli military is coming under rare and rising scrutiny due to the war in Gaza. Our charts put the debate in context.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

In the newsroom, we often talk about counternarratives. It can be easy for societies or certain swaths of the media to become fixated on one aspect of a story. Often, the truth involves more nuance.

Both today’s article by Laurent Belsie and Leonardo Bevilacqua, and our editorial are great examples. Yes, artificial intelligence is a potential threat in some ways and requires careful thought. No, it will not destroy the world by next Tuesday.

Maybe there could be some surprising benefits along the way. Maybe impending doom is not the only narrative.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 4 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Russia detains U.S. soldier: The U.S. Army says the soldier arrested in Russia late last week is being held in a pretrial detention facility.

• New effort to oust speaker: Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene has called for a vote to oust Speaker Mike Johnson.

• Transgender regulations challenged: Seven more Republican states are suing to challenge a new federal regulation to protect transgender student rights.

• Trump trial postponed: Former President Donald Trump’s trial in Florida on charges of illegally keeping classified documents after leaving office has been indefinitely postponed.

• Olympic torch in France: A majestic three-mast ship carrying the Olympic torch arrives in Marseille from Greece, bound for a sunset welcoming ceremony.

( 5 min. read )

And here, the doomscrolling can officially stop. At a story about artificial intelligence, no less! Yes, there are ways that AI can genuinely help – and no one is talking much about them.

( 4 min. read )

In 2010, NATO soldiers marched in Red Square alongside Russian troops to celebrate Victory Day, recalling the end of World War II. This year, NATO takes the conspicuous role of enemy.

( 5 min. read )

Six months ago, young Poles made a statement by helping to vote out eight years of increasingly antidemocratic rule. Their prize? The realities of governance.

( 5 min. read )

Fencing has a reputation as an elite – and sometimes elitist – sport. A group of young athletes in Nairobi, Kenya, is shattering that stereotype and forging Olympic dreams.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

The future of the global economy has “brightened,” found the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group of 38 wealthy countries. The OECD’s economists cited many factors for a potentially better rate of growth. But one stands out: a rapid rise in the use of artificial intelligence to improve worker productivity.

The OECD cited a couple of examples: People who write for a living and now rely on AI are about 50% more efficient. Computer coders are 60% more efficient.

These gains are “huge,” Clare Lombardelli, OECD’s chief economist, said last week. Yet they don’t quite capture future gains, she added, as the world begins to use AI to change “what we do as well as how we do it.”

That’s not all. The promise of AI to boost output per capita may help counterbalance a widespread worry that the future is hindered by a “scarcity of ideas,” according to an OECD report in April. The reason: AI, which is innovative enough, has begun “triggering an acceleration of innovation.”

Companies adopting AI have produced higher numbers of patents and new products. In particular, Al will enhance basic research by quickly generating new hypotheses that will then yield new inventions. This will allow researchers to “go beyond the low hanging fruits of scientific discovery,” the OECD found. AI “may continuously push out the productivity frontier.”

Ideas “are different from nearly all other goods in economics,” said Charles Jones of the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research at a symposium last year. Unlike material goods or workers, ideas do not have rivals because they are “infinitely usable” by any number of people.

“In the long run, growth in living standards is determined by growth in the worldwide number of people searching for ideas,” he said. That number is determined by available talent, level of investments, migration patterns, and the size of the world population. As for AI’s potential to boost growth, he added, it is “perhaps the most uncertain but also has the greatest upside potential.”

“Artificial intelligence appears to be a new general purpose technology, perhaps on par or even exceeding electricity and the semiconductor,” he said.

For all its potential for misuse, AI at least has begun to alter how the world thinks about sources of inspiration. Or as economist Paul Romer, a winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, has noted, “We consistently fail to grasp how many ideas remain to be discovered.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 4 min. read )

When we let a Christ-inspired view of things lift us out of unhelpful modes of thought, this opens the door to progress.

Viewfinder

Palestinian children play during the Eid al-Adha holiday, in Gaza City, June 6, 2025.

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for a story from Sudan, where rape has become a weapon in the country’s brutal civil war. But now, some women are refusing to be silenced and are building community with one another.